This appeared in The Soho News on March 11, 1981. A month earlier, I had launched a kind of weekly column there called “Declarations of Independents” that was in diary form — a bit like some of my Paris Journals and London Journals for Film Comment during the 70s –- and this was the third of these. — J.R.

Feb. 24: Why go all the way to the Thalia tonight to see five Screen Directors Playhouse episodes, all half-hour TV shows from the mid-50s? Two professional reasons spring to mind, both essentially recycling operations. As often happens in such cases, I feel myself split between the two — processes that honor my asocial aesthetics on the one hand, my social politics on the other.

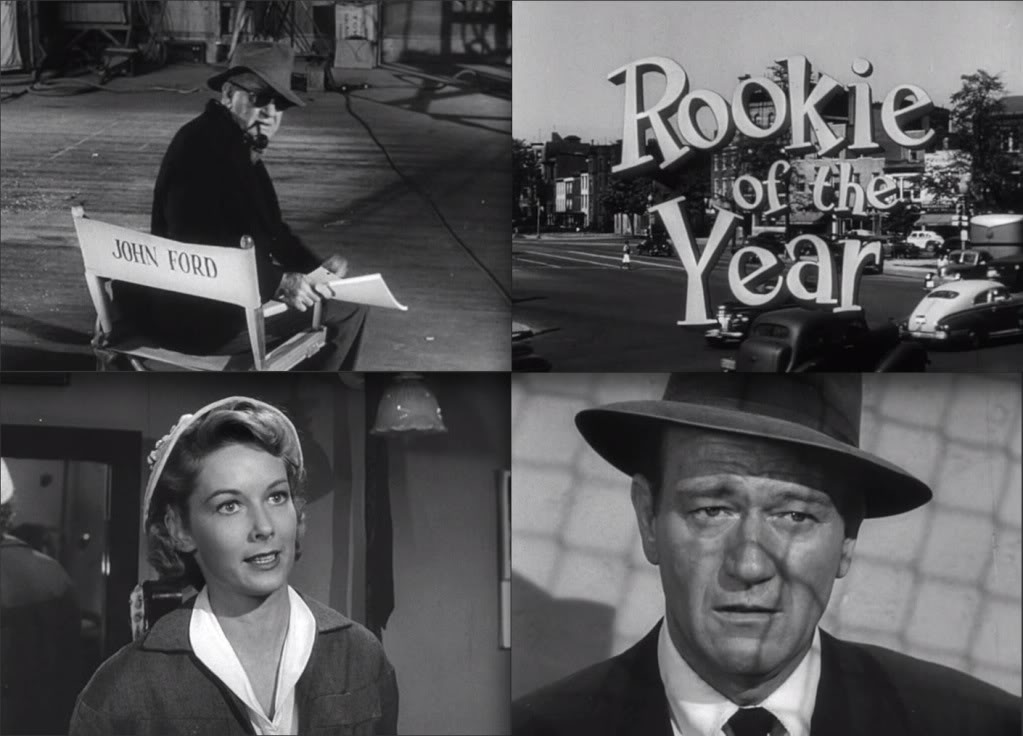

Auteurist Retrieval technology (we’ll call it ART for short) — cultivated by me and a lot of other film freaks in the late 60s — is predicated on the pleasure of recognizing the taletale signs of favorite directors in all sorts of unlikely material. And what better excuse to put ART to work than patriarchal episodes by John Ford, Leo McCarey, Frank Borzage, Tay Garnett, and William Seiter? Indeed, to narrow the focus down to the evening’s main event, what better specimen could one hope to find but a crisp 35mm print of Ford’s Rookie of the Year, made immediately before his masterpiece The Searchers, with the same scriptwriter (Frank Nugent) and no less than four of the same actors — John Wayne, Pat Wayne, Vera Miles and Ward Bond — playing central roles?

Professional reason No. 2 has more to do with my relationship to the period when these shows were made (all of them at the Hal Roach Studio, sponsored by Eastman Kodak — “with all the scope and realism that only motion picture techniques make possible,” and with each week’s preview offering a glimpse of next week’s director at work at work in a canvas chair bearing his name). The process here, based on personal and historical research — which in my case evolves directly out of work on a book called Moving Places (Harper & Row/Colophon) in the late 70s — might be called Identity/Ideology Retrieval Systems, or IRS for short. By and large, it regards the cinephilia of ART therapeutically, as a disease to be cured, and chiefly addresses itself to the world outside cinema. In other words, ART, like most ordinary moviegoing, aims at obliterating or at least concealing one’s own identity and that of the world outside the theater; IRS aims at constructing and/or restoring them both.

Reasons No. 1 and No. 2 are a quarrelsome marriage of convenience, to say the least, especially when they decide to attend a movie together. In support of ART is a useful, mimeographed “weekly guide to the writers and directors of TV movies and episodes” that I find in the Thalia lobby, available from Barry Gilliam, 4283 Katonah Av., Bronx 10470 ($5 for 15 weeks, $15 for a year) — a nifty little newsletter that can allow you to waste oodles of time engaged in supposedly Scholarly Pursuits (see Feb. 25), while investing the mundane with vast amounts of potential stylistic significance.

In support of IRS are the motley, fascinating trailers that are nowadays a Thalia specialty, many of them quite functional and revealing as time machines. Among tonight’s highlights are previews for Sepia Cinderella, La Dolce Vita, High Noon, The Rainmaker and Harold and Maude — the latter less than 10 years old yet substantially more dated than the rest, because the color deterioration is so pronounced that everything on the screen has become a different shade of blue.

ART could probably devote a day or so to tracing all the Fordian internal and cross-references in Rookie of the Year, e.g., John Wayne’s son Pat in both films used in filial relation to Ward Bond as well as his own dad, or the deliberate suppression of a news story which sets history straight, anticipating The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance by seven years. But this pedantic formalism invariably misses the perverse sexual undertones in the myths involved — a factor that IRS could help to supply.

Rookie of the Year (1955) tells the tale of Mike (John Wayne), a small town sports reporter who flies to the World Series so he can get a good look at Lyn Goodhue (Pat Wayne), a rookie who’s just appeared on the cover of Time. Noticing that Lyn plays just like Buck Garrison (Ward Bond) — a rookie kicked out of baseball for taking a bribe 20 years ago — Mike proceeds to the kid’s hometown. There he substantiates his hunch that Lyn is Buck’s son — a fact that Ruth (Vera Miles), who’s in love with Lyn, persuades him to suppress.

All in all, it’s a plot about as convincing as Eyewitness (featuring William Hurt as a janitor who owns a Betamax). What gives it a particular life of its own is the powerful, flirtatious erotic tension between Mike and Lyn in a locker room, when the latter remarks, “For a man your age, you look okay.” It’s every bit as intense as the explicitly incestuous undercurrents in Wayne’s relationships to Jeffrey Hunter and Natalie Wood in The Searchers — which the prudish, conservative ART critics shy away from, ignoring even the suggestions that both these characters are the hero’s illegitimate offspring. It has all the eroticism missing from the scenes with Vera Miles in the two films, where she invariably gets wedged in between the men (the Duke and Bond in Rookie, the Duke and Hunter in Searchers) and then ignored, like a soft whoopie cushion that periodically emits comic punctuation when squeezed.

***

Feb. 25: Delayed over half an hour by a basketball game, Robert Altman’s made-for-TV thriller Nightmare in Chicago (1964), at once efficient and interminable — expanded with outtakes from a “Kraft Suspense Theater” episode, according to Gilliam’s informative guide — finally gets started on Channel 9. Apart from offering more routine ART fodder, like a protracted nightclub striptease that could easily be cross-indexed with Gwen Welles’ in Nashville, the only striking directorial touches I notice in this formula killer-manhunt story are subjective renderings of the lunatic’s mind: his mother’s whispered admonishments to him as a tot and the painfully piercing brightness of lights, both magnified in a neoexpressionist manner.

It’s just one more example of Altman’s free-floating cleverness before he was unlucky enough to be turned into an auteur by overeager ART enthusiasts, yieldeng such tin-plated testimonials to middle-brow seriousness as Images, Three Women, and Buffalo Bill and the Indians. As someone who regards Altman’s mature work as a reflection of teamwork and certain utopian hopes about collectivity during the 70s, from the ramshackle frontier town of First Presbyterian Church in McCabe and Mrs. Miller to the comparably makeshift and jerrybuilt port town of Sweethaven in Popeye — hopes that were born, took shape, became problematic, and then either died or redefined themselves in order to survive — I can only lament the crass process in American criticism that foisted the role of Lone Independent Thinker and Arthouse Sage on Altman and then penalized him for not living up to it. (Where are these fairweather friends now, when he can’t even get his latest film Health released?)

Feb. 26: At thre Art to see a stereo print of Guys and Dolls (1955), near the end of their poorly attended Sam Goodwyn season, I fortuitously get to see the trailer of Northern Lights, which automatically puts some dramatic IRS into effect. This is because First Run Features has just finished showing me Northern Lights in its entirely in their office screening room less than an hour ago, on a much smaller screen, and the differences in meaning and impact brought about by a different size and context are truly startling.

Partially because I’m also seeing a trailer, the same pictorial black-and-white shots of North Dakota farmers organizing in the winter of 1915-16 have become less naked and more Hollywoodish, bolder and less ambiguous, all dressed up with some place to go. This drives straight into the heart of the contradiction of this film and the 3 1/2-month season of American Independent Films that it spearheads — hat it doesn’t want to go Hollywood, yet given the present media setup (which ultimately stipulates only one game in town, win or lose) it essentially has to in order to get anywhere at all.

Guys and Dolls, on the other hand, which I last saw on BBC-TV in London five years ago, doesn’t really gain much by filling up a sizable screen — despite a city-as-set conceit that might have worked (but doesn’t) as a primitive Manhattan forerunner to the Paris of Playtime. The problem is, Joseph Mankiewicz can’t shoot a musical, gets confused on issues of time and space — accounting for the all-around antipathy of most critics for this cramped, overlong Runyon and Loesser revue.

But Guys and Dolls has something else going for it. Part of the time, this is a fiercely disassociated competition between Marlon Brando and Frank Sinatra in separate parts of the movie that recalls Jazz at Massey Hall, a concert album in which Dizzy and Bird studiously and disinterestedly try to nail each other to the wall. Yet as soon as Brando and Jean Simmons share the screen, the heavy calisthenics stop, the movie starts, and something much more interesting takes shape — a sexy rapport between two consummate pros (as actors) and amateurs (as singers), worming their way into privileged pockets of the movie, crooning perfect;y balanced duets that melt my socks off. (This is their second movie together, by the way; they became chums while doing Desiree in ’54.)

To hell with those boring Joe Palooka (and Palookaville) erotics that dictate that the best Brando performances are always the most violent ones, the Streetcar Waterfront One-Eyed Tango struts that have already encouraged a generation of slobs to become louts, too. The sheer delicacy of the Big B’s two tours de force in 1955 are scoffed at as sissy work, yet his extraordinary Japanese choral figure in Teahouse of the August Moon (revisted at the Regency about a month ago, and more recently visible on TV) and his Damon Runyon dandy here are often wonders to behold — especially, here, when he has Simmons’ sinuous rhythms to play against. Chemistry? Yeah, chemistry.