Written for my “En movimiento” column in Caimán Cuadernos de Cine in July 2015. — J.R.

En movimiento: Young Orson

Jonathan Rosenbaum

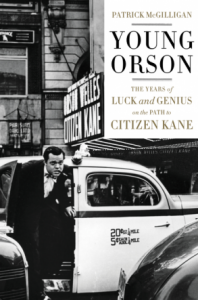

Out of all the discoveries that have come my way in the wake of the Welles centennial, the most interesting and exciting so far has been Patrick McGilligan’s Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane, a biography that comes to 785 pages, at least in the bound uncorrected proofs sent to me by HarperCollins in mid-July. (The official publication date is November 17.) As I wrote in a blurb solicited by the publisher, “In many ways, Patrick McGilligan’s Young Orson is my favorite of all the Welles biographies to date. Not only because he’s read all the others, and makes judicious calls about how far we should trust them, but because his own prodigious research has turned up so much rich, fresh, and clarifying material. The overall portrait of Welles’s character and background that emerges, uncharacteristically sympathetic, is both dense and persuasive — and a page-turning pleasure to read.” I’m especially impressed by how much McGilligan has turned up about Welles’s parents, his guardian, and his childhood in general.

This isn’t to say that I don’t have qualms about some of the particulars in McGilligan’s vast array of material. Based on my own meeting with Welles in 1972 to discuss his first project for a Hollywood feature, Heart of Darkness, I think McGilligan overestimates the role played by John Houseman in the writing of that very detailed screenplay. (According to Welles, Houseman wasn’t even present at any of the script conferences, and his lack of enthusiasm for the project — the unrealized Welles feature that probably received the most detailed preproduction of any in his career — is evident in Houseman’s memoir, Run-through, which McGilligan rightly treats with some circumspection.) And in his final chapter, a sort of flash-forward to the last day of Welles’s life, October 10, 1985, he is much too vague about what Welles was planning to shoot with Gary Graver in Los Angeles the following day; according to Graver, who would have known, this was a much-abridged version of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar without Brutus, conceived as part of a compilation that was tentatively titled Orson Welles Solo.

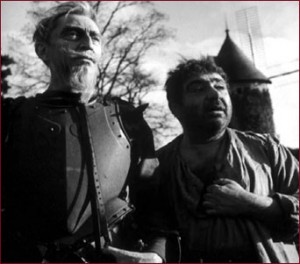

But the problem of conflicting accounts about Welles projects persists throughout his career, so it is hardly surprising that McGilligan should run into such difficulties with the first and last of Welles’s California-based film projects, as well as a good many others. A master of improvisation, Welles was fully capable of changing his mind about the basic design of his projects on a daily or sometimes even hourly basis, so the issue of trying to complete or even theoretically describe such unfinished features as It’s All True, Don Quixote or The Other Side of the Wind by trying to make them confirm to his “intentions” is not only fraught with perils but founded on a basic misunderstanding of how he normally functioned. (To a lesser extent, the same problem exists with features completed by others, such as The Magnificent Ambersons, The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin, and Touch of Evil, and with still other features that Welles himself completed more than once in separate versions, such as Macbeth and Othello.)

McGilligan’s attitude towards the man is supportive, but he rarely stoops to hagiography. A complex portrait of Welles’s character emerges that doesn’t overlook his mercurial temperament but also doesn’t waste much time with psychologizing or attempting to resolve all the contradictions in his behavior. We come to realize, for instance, that Welles’s reputation for marital infidelity was tempered by (1) a conscious desire not to refute false rumors and (2) a passion for Platonic relationships that probably weren’t as sexually active as other biographers have assumed. A careful fact-checker, McGilligan shoots down the popular notion that Welles was the father of Michael Lindsay-Hogg, after showing that the travel dates of the mother, Geraldine Fitzgerald, and the location of Welles at the time, on a separate continent, made this impossible.

After my single meeting with Welles, I felt that he was both unusually self-absorbed and acutely aware of it, eager to compensate with a great deal of generosity. McGilligan expands on this singular trait with novelistic gusto.