From the Chicago Reader (October 27, 1995). — J.R.

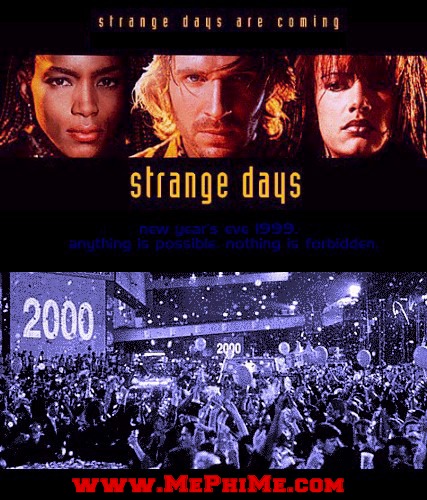

Strange Days

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Written by James Cameron and Jay Cocks

With Ralph Fiennes, Angela Bassett, Juliette Lewis, Tom Sizemore, Michael Wincott, Vincent D’Onofrio, Glenn Plummer, Brigitte Bako, and Richard Edson.

In the introduction to his recently published first draft of the Strange Days screenplay, James Cameron offers a candid, suggestive description of what working on the script was like: “The problem was I had never written anything remotely this densely plotted and character driven. I circled and circled the computer, like a dog slinking around trying to work up the courage to steal food from a sleeping drunk.”

Cameron’s simile could be seen to apply not so much to Strange Days and other overhyped media events as to the sort of measures our legislators have been pushing through Congress lately. These measures more or less state that we can no longer afford to coddle criminals, the elderly, crack babies, the poor, the sick, or the homeless or support art, culture, or education — not because we’re living through any kind of depression but because millionaires still aren’t making as much money as they want to. Assuming that we’re the sleeping drunk in this scenario, it’s worth asking what sort of dreams we could possibly be having that would allow those congressional canines to find the courage to slink around us with this kind of hope. This is where Strange Days and those other overhyped media events come in.

To me, it’s a toss-up whether these dreams have to do with Strange Days or Seven or the O.J. Simpson trial and its countless spin-offs. The objection will be raised that the Simpson hoopla is about something real. I suppose it is, but considering how much of the rest of the news — that is, news of the rest of the world — has been suspended or omitted for the sake of “in-depth” coverage of O.J., it’s pretty clear that this hoopla is supposed to stand mythologically and emotionally for everything that’s being excluded. In other words, real or not, the story plays out in our heads like a symbolic drama — like a big-budget movie, in short, except that it’s much longer. And it’s meant to signify much more to us than our own lives possibly could. Whichever side one takes on the issues, the O.J. trial and verdict are made to carry such overbearing weight that the remainder of our national life — including daily instances of murder and wife beating — is diminished.

Indeed, it may be more pertinent to consider what Strange Days, Seven, and the ongoing O.J. serial have in common: movie stars, violence, drama, jealousy, money, police, racial turmoil and interracial bonding, snuffing women and male rivals, and so on. This excitement can’t be matched by the mere prospect of seeing our country sold down the river. So if Congress winds up voting to grant even more money to the Pentagon than the Pentagon requested and slashes countless social benefits that affect us all, why should we worry? We have the much more pressing issue of the guilt or innocence of one celebrity on our minds.

It could be countered, of course, that Strange Days is anything but escapist. Unlike Seven, which is making lots more money, Strange Days is about the corruption and racism of the LA police force — though the worst offenders are miraculously exposed and brought to justice in a matter of minutes, thereby terminating a full-scale race riot in seconds. It’s also about urban blight, media escapism, soulless thrill seeking, even the viewer’s own guilty voyeurism. In fact, that’s what I find most objectionable about this movie — the hypocritical pretense that it’s doing and saying something serious.

If action sequences are all you’re after, director Kathryn Bigelow is a lot better than most at putting them together; and in interviews she spouts a fair amount of reasonably intelligent art-school patter. But her gifts don’t mean that Strange Days is improving the state of the world or even changing the way we think about it. Perniciously, the filmmakers spend almost two and half hours trying to convince us otherwise — or, rather, trying to get us to con ourselves into accepting such a proposition so we won’t leave the theater feeling like jerks. The first time I saw this movie, two months ago, in a well-equipped screening room, I was gripped if not always convinced; the second time, last weekend at Webster Place, I was mainly bored out of my skull. It’s amazing what a good Dolby system can do in getting you to overlook your own intelligence. So if that’s what you want to do to yourself — and I can’t imagine any other reason to see this picture — look for the theater with the best sound system.

Cameron notes that he first dreamed up Strange Days in 1985, when the notion of “a film noir thriller taking place on New Year’s Eve 1999” must have seemed even more apocalyptic. The script’s relatively early genesis probably helps explain its old-fashioned ideas about modernity, despite some in-your-face updates that are supposed to remind you of Rodney King and the subsequent riots; in fact, “moderne” seems a much better adjective for the décor and overall ambience than “modern.”

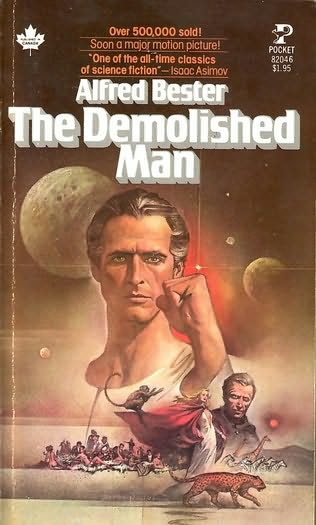

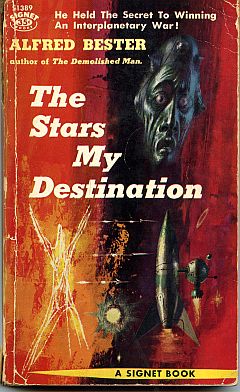

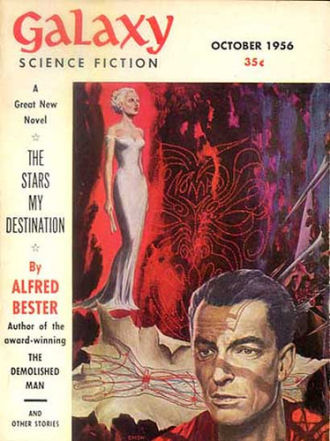

The sadomasochistic, paranoid hysteria of the pedestrian mystery plot and Blade Runner atmospherics of Strange Days evoke the first two SF novels of Alfred Bester, The Demolished Man (1953) and The Stars My Destination (1956). The film’s central conceit — that sensory recordings are made of people’s experiences — is like a hasty update of the “feelies” in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932). And the notion of a woman being forced to view herself while she’s brutally raped and/or murdered is clearly borrowed, along with a great deal else, from Michael Powell’s brilliant Peeping Tom, a work of slightly more recent vintage (1960).

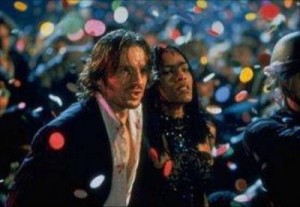

Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes, who’s again failed to master an American accent), still grieving the loss of his rock-singer girlfriend Faith (Juliette Lewis) to her evil agent (Michael Wincott), was once a cop but now traffics in black-market “clips” (the aforementioned sensory discs). Unlike this movie, however, Lenny refuses to deal in real or ersatz representations of rape and murder — which is what makes him the hero. A prostitute and porn actress (Brigitte Bako) who’s previously done recordings for him is running for her life, trying to get Lenny’s help and warning him that Faith is in danger as well. Before she can explain, she’s whisked away by the plot, and later Lenny finds himself sampling a playback of her brutal rape and murder. Other characters include Lenny’s two confidants — another ex-cop (Tom Sizemore) and a security driver named Mace (Angela Bassett), whose husband Lenny helped arrest when he was still a cop — and a radical rap artist named Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer) who’s found brutally murdered shortly before the story begins, on December 30.

Part of what passes for novelty in this lurid plot is the degree to which Mace figures as the film’s action hero rather than Lenny, who’s a spiritual and physical wimp. She repeatedly pulls him out of scrapes, defends him from beatings with her physical prowess and her firepower, and even helps revive him when he faints, like a fluttery heroine, at the climactic New Year’s Eve revels. A wise, practical-minded, resourceful dominatrix, Mace is more a vehicle for Bigelow’s undeniable talent with action sequences than a believable character in her own right. Her maternal devotion to Lenny is fairly inexplicable, unless you consider the fact that she’s black: her role conforms to an ideological agenda neatly outlined by Benjamin DeMott in the September Harper’s magazine, in an article called “Put On a Happy Face: Masking the Differences Between Blacks and Whites.”

Citing no fewer than 40 recent, prominent American movies that “deliver the good news of friendship” between black and white characters, “suggesting that the beast of American racism is tamed and harmless,” DeMott skillfully demonstrates how such superficial bondings are a kind of con job that produces feel-good movies. This is true even in films like Strange Days, where the backdrop for the interracial bonding is a universe of racism and racial discord: just about all one sees of the streets of Los Angeles are robberies, muggings (including one of Santa Claus), street gangs, riot squads, and the National Guard. (For all this country’s hatred of crime, poverty, and street violence, as evidenced by “our” recent legislation, sometimes it seems Americans enjoy little else when they go to the movies.)

“Look around, the whole planet’s in fucking chaos,” says a self-justifying villain in Strange Days at one crucial juncture. But since the only violence in this movie is local, it’s hard to see how we can come to any conclusions about the state of the planet — unless we want to be as arrogant and hypocritical as this movie is about our own escapism.

We see reaction shots of Lenny perhaps most often when he’s watching his sensory discs — either smiling (once or twice) when he’s playing back sexual gambols with his former girlfriend or groaning and grimacing (much more often) when he’s watching someone getting raped or murdered or both. You might wonder why, if he hates these playbacks so much, he keeps on playing them back. Why, for that matter, do we? I suppose, in their more lucid moments, that’s what Bigelow and her screenwriters think they’re asking us. But in the end that question is as self-serving as the claim, on the basis of very little, that the whole planet’s in chaos. What this movie is ultimately saying is, don’t think at all.