This appeared in the August 22, 2003 Chicago Reader, and has more recently been reprinted in the excellent Camera Lucida. On the afternoon of September 17, 2014, in Sarajevo at the Film.Factory, I screened this for the MA students and assigned them to create five-minute remakes. We screened most of the results nine days later at a party, and they were really dazzling — and all quite different from one another. — J.R.

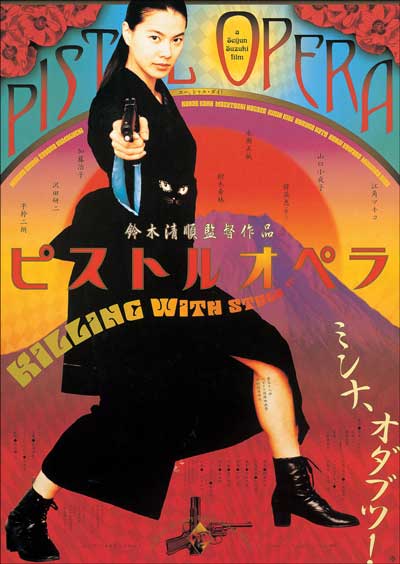

Pistol Opera

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Seijun Suzuki

Written by Kazunori Ito and Takeo Kimura

With Makiko Esumi, Sayoko Yamaguchi, Masatoshi Nagase, Kan Hanae, Mikijiro Hira, Kirin Kiki, Haruko Kato, Yeong-he-Han, and Jan Woudstra.

Can I call a film a masterpiece without being sure that I understand it? I think so, since understanding is always relative and less than clear-cut. Look long enough at the apparent meaning of any conventional work — past the illusion of narrative continuity that persuades us to overlook anomalies, breaks, fissures, and other distractions we can’t process — and it usually becomes elusive. Yet it’s also true that we have different ways of comprehending meaning. I once watched some children listen to passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, possibly the most impenetrable book in the English language, and saw them burst into giggles, plainly understanding better than the adults that this was exactly the way grown-ups talked, only funnier.

I first saw Seijun Suzuki’s Pistol Opera (2001) in early 2002, and half a year later I served on a jury at an Australian film festival that awarded the movie its top prize, calling it “a highly personal blend of traditional and experimental cinema.” I can’t think of another film I’ve seen since that has afforded me more unbridled sensual pleasure. Which may explain how I could dip into an unsubtitled DVD any number of times and never worry about not understanding it. (I should note, however, that this film, starting with the eye-popping graphics of the opening credits, needs the big screen to achieve its optimal impact.)

I couldn’t give a fully coherent synopsis of Pistol Opera if my life depended on it, but it’s still the most fun new movie I’ve seen since Mulholland Drive and Waking Life (both also 2001). Yet I have to admit it must not be everybody’s idea of a good time: the Music Box is showing it only this weekend and only at midnight and 11:30 AM, and even in Japan it seems to be strictly a cult item and head-scratcher.

Having recently seen the movie again with subtitles and read a few rundowns of the plot, I’m only more confused about its meaning. The gist of the narrative is that a beautiful young hit woman known as Stray Cat (Makiko Esumi) — “No. 3” in the pecking order of the Guild, the unfathomable, invisible organization she works for — aspires to be No. 1 and proceeds to bump off most of her male colleagues.

They include Hundred Eyes, aka Dark Horse, a young dandy with chronic sinus problems who’s currently No. 1; Goro Hanada (a character revived from Suzuki’s 1967 Branded to Kill), who’s middle-aged and walks with a crutch, answers to the name of “The Champ,” and used to be No. 1; the Teacher, No. 4, who’s middle-aged and gets around in a wheelchair; Dr. Painless (Jan Woudstra), No. 5, a Westerner who’s built like a Viking and periodically speaks English; and, apparently, Lazy Man, No. 2, who’s referred to many times and cited in the credits but whom I seem to have missed. To complicate matters further, many of these men are killed by No. 3 not once but repeatedly, springing back to life like Wile E. Coyote in a Road Runner cartoon — and some of them kill Stray Cat repeatedly as well.

In between these deadly encounters Stray Cat has scenes with females from at least four generations, including a grandmotherly rustic woman who takes care of her; the former No. 11, who sells her a Springfield rifle; a middle-aged agent with a bright purple scarf mask who sends her on missions and periodically flirts with her; and a little girl named Sayoko who speaks more English than Dr. Painless (reading or reciting, among other things, “Humpty Dumpty” and Wordsworth’s “Daffodils”) and clearly wants to grow up to be a hit woman herself.

The scenes with the rustic woman and Sayoko tend to register like relaxed family get-togethers. The other meetings with men and women often start as Guild assignments and wind up, at least symbolically, as sexual assignations, full of taunts, teases, and gestures that drip with innuendo. They also come across like children’s games: the blade of Dr. Painless’s knife is collapsible, all the guns are bandied about like phallic toys or fetish objects, and any pain is clearly make-believe. (As Godard once said of his Pierrot le fou, the operative word is “red,” not “blood.”)

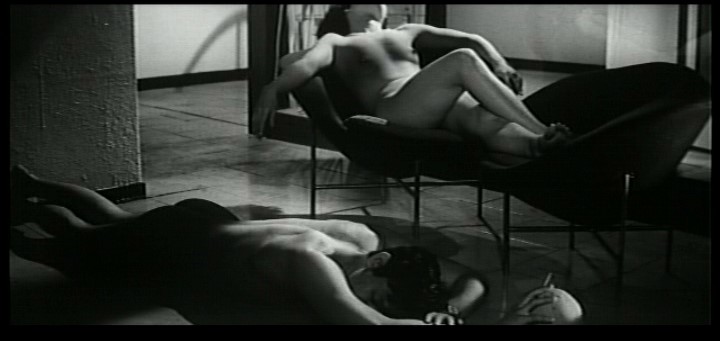

Static poses are often struck; the story unravels more like a ballet than an opera (the movements of actors and camera as well as the cuts are synchronized to pop music, much of it performed on trumpet by a Miles Davis clone); and the action shifts between industrial, rural, or urban locations that are used theatrically and studio sets that often take the form of theatrical stages used for Kabuki, butoh, and Greek or Roman drama (we see columns suggesting a Mediterranean amphitheater). Other scenes appear to be set in some lava-lamp version of an afterlife, with an otherworldly lime-colored dock and a shimmering gold river over which ghostlike figures in white hover.

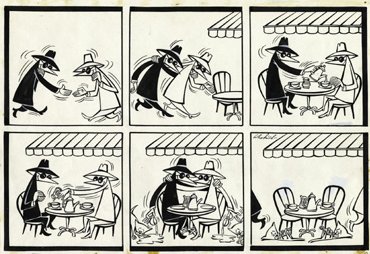

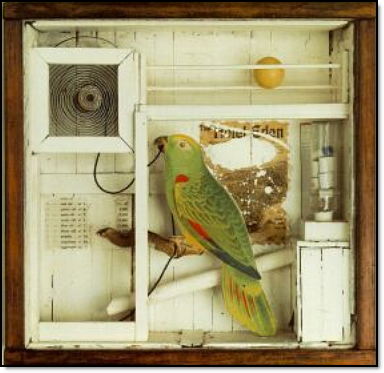

I don’t subscribe to notions of “pure cinema” or “pure style,” because even abstraction has content — color, shape, movement. But this free-form and deeply personal movie suggests purity more than any other recent film that comes to mind. It’s often as abstract and as stringently codified as Cuban cartoonist Antonio Prohias’s Spy vs Spy comic strip in Mad, though the color of most of the kimonos is too gorgeously lush to evoke Prohias’s minimalism. And the feeling of sacred passion conveyed by many of the compositions — the sense that many of the characters, costumes, props, and settings are the objects of Suzuki’s unreasoning worship, as carefully placed and juxtaposed as totems in a Joseph Cornell box — imbues the whole film with some of the aura of ecstatic religious art, even if it’s cast in the profanely riotous pop colors of a Frank Tashlin.

Suzuki, who turned 80 last May, directed at least 40 quickie features at the Nikkatsu studio between 1956 and 1967 — practically all of them B films in the original sense of that term, meaning features designed to accompany A pictures. I’ve seen half a dozen of these, ranging from the 40-minute Love Letter (1959), a black-and-white ‘Scope film with a ski-lodge setting, to the 91-minute Branded to Kill, a baroque hit-man thriller (also in black-and-white ‘Scope) that remains his best-known work — and was, along with Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le samourai, the major inspiration for Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog.

Branded to Kill so enraged the president of Nikkatsu that he fired Suzuki for making “incomprehensible” films. A Suzuki support group was duly formed, and Suzuki sued the studio, as he later put it, “to protect my dignity.” A full decade would pass before he directed another theatrical feature, and he never returned to Nikkatsu. His output became sporadic, much of it consisting of TV commissions, and eight years of silence preceded Pistol Opera.

Before Pistol Opera I wasn’t one of Suzuki’s most ardent fans. Frankly, I didn’t know what to make of him, even as a cult figure. According to my favorite Japanese film critic, Shigehiko Hasumi, “Suzuki is appreciated in the West, but essentially he’s a traditional Japanese man who regards Western people as barbarians, in the traditional Japanese meaning of that term.” This implies that one can’t adequately (or accurately) rationalize his craziness by calling him a Japanese Sam Fuller, and one can’t palm him off as an old pro churning out entertainments, though that’s how he represents himself, at least in part.

In a 1997 interview in Los Angeles included on the DVD of Branded to Kill, Suzuki, after insisting that he just wants to make films that are “fun and entertaining,” goes on to argue that there’s no “grammar” for cinema — at least for his kind of cinema — because he doesn’t mind defying the usual rules respecting the cinematic coordinates of time and space: “In my films, spaces and places change [and] time is cheated in the editing. I guess that’s the strength of entertainment movies: you can do anything you want, as long as these elements make the movie interesting. That’s my theory of the grammar of cinema.”

This may sound like a recipe for formalism — especially given that the film’s subtitle is Killing With Style — but there’s far too much content in Pistol Opera to make its dream patterns feel arbitrary or reducible to a simple theme-and-variations format. Indeed, one of the reasons I find the film so exhausting is that it doesn’t take time out for anything. Whatever it’s after, it always feels on-target.

Suzuki’s protracted hiatus from filmmaking may be partly responsible for the sense of manic overdrive. Orson Welles once speculated that the hyperbolic style of his Touch of Evil was the consequence of feeling bottled up creatively for much too long, and considering all the striking and even stunning locations used in Pistol Opera, I’d like to imagine that Suzuki spent years discovering them, saving them for whenever he’d be able to show them off in a film.

Obviously the movie has a lot to do with gender. There’s the dominance and aggression of the women (not counting the country grandmother, who seems to belong to a different era), combined with Stray Cat’s phallic preoccupations (“I think it’s OK to lead my life as a pistol,” she says at one point; elsewhere she addresses her gun as “my man”) and the pronounced disability of the men (not counting Dr. Painless, who appears to signify “America”) — all of which seems like a precise inversion of the structure of Japanese society. The other themes are no less Japanese. There’s the obsession with hierarchy, competition, and professional identity. There’s the surrealist view of death as lyrical expression: according to the Champ, “Killing blooms into an artwork,” and a steam shovel turns up at the door of a rural cottage with rose petals dropping from its jaws. More subtle and profound is the memory of military defeat, made explicit in one of the masked agent’s late soliloquies and in a vision of a mushroom cloud that suddenly appears on a rotating stage. Most of these themes seem to come together in the former No. 11’s climactic speech about a dream she had in which a headless Yukio Mishima appears and she tries without success to sew his head back on, using all sorts of string and wire.

In fact, Pistol Opera registers as so prototypically Japanese in both style and content that the preponderance of English dialogue is notable mainly for the sense of foreignness it conveys. My favorite howler in the dialogue — “I didn’t mean to kill each other, really” — sounds like the way adult Americans talk, only funnier. It also perfectly conveys the Japanese language’s conflation of singular and plural and all the ambiguous crossovers between self and society that seem to derive from this.

The absence — or rather sublimation — of sex is equally operative. “I don’t really like sex,” Suzuki declared in a 1969 interview. “It’s such a hassle.” He then responded to the question “In which period would you have liked to be born?” with the equally defeatist “Well, not as a human, in any case.” At first it may be difficult to reconcile this negativity with the film’s sense of joyful discovery, but the dream logic whereby opposite attitudes produce each other seems central to Pistol Opera — an ambivalence that’s conveyed even by its title.