Program notes for this double feature at Manhattan’s Public Theater, March 8-13, 1983. A few of the arguments here, such as the comparison of Driver with Straub, strike me now as forced, but when I recall that students in the Downtown Whitney program during the same period compared You Are Not I abusively to The Twilight Zone (and were equally reluctant to regard John Ford as a serious artist when Straub praised him), I think my polemics were warranted….A happy postscript: both films are now available in excellent digital restorations (see below). -– J.R.

Slow yet relentless in their narrative progressions, deliberately nonspecific in their period settings, and equally unimaginable in anything but black and white, YOU ARE NOT I (1981) and THE HONEYMOON KILLERS (1969) are both startling and achieved first films about the triumphs of inexorable wills — each made with a kind of rigor and passion that seem oblivious to the whims of fashion. Small wonder that François Truffaut should be enthusiastic about the earlier film, with its accelerating montage of breathless love letters, its flighty camera movements and implacable bursts of Mahler; or that Jean-Marie Straub should be enthusiastic about the later one (“I liked your film ten times better than Roger Corman’s Edgar Allen Poe movies”), with its integral use of dialectics in conception and treatment alike. Both films are American to the core, yet they occupy a genre, “the art film”, that is mainly European in its low-budget manifestations. (YOU ARE NOT I cost $14,000 to make, THE HONEYMOON KILLERS, $150,000) — neglected and relatively unprotected by American institutions (as opposed to “mainstream,’ and “avant-garde” films), hence more difficult in most circumstances for us to see.

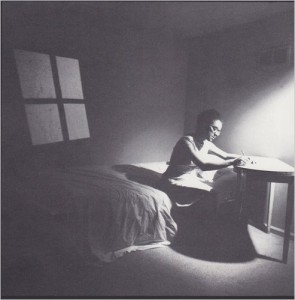

What’s dialectical about Sara Driver’s film, a very close adaptation of a Paul Bowles horror story written in the late 1940s? As in many of the heroic and mock-heroic compositions of Straub and Huillet, bodies are juxtaposed against landscapes, off-screen voices against on-screen fictions, surrealist fantasies of the unbridled ego against documentary representations of its confinement, and momentary subjective flashes against longer and broader meditations, e.g., the powerful movement from still shots of two old women pressed against a wire fence to a one-shot sequence that starts with Ethel (Suzanne Fletcher) walking past them -– like a quick trip from Chris Marker’s LA JETÉE to Antonioni’s LA NOTTE. The divided self — the art and craft of schizophrenia — thus becomes the film’s method as well as its subject (beginning more or less the same way that PSYCHO ends), and the fierce battle of wills, world-views, and intelligences between the two sisters dictates the formal separations in Driver’s stark approach.

Significantly, both filmmakers were formed by other disciplines: Driver comes from theater and archeology, Leonard Kastle composes operas. And while Driver’s work with both her actresses and her tendency to build both her sounds and images in layers seems to reflect her respective interests, Kastle’s use of a rather operatic heroine whose passionate determinations are often signaled by snatches of Mahler echoes aspects of his own professional background.

There’s plenty in THE HONEYMOON KILLERS to remind one of other movies: Martha (Shirley Stoler) kicking a toy wagon from her path is a gestural detail worthy of a Cagney, and the whole plot evokes the petit bourgeois equation of business and murder broached by Chaplin’s MONSIEUR VERDOUX. But perhaps the most remarkable thing about it remains its fidelity to a particular kind of American awfulness that most films ignore. Some of this is merely an accuracy of domestic detail: the Reader’s Digest Condensed Books in Valley Stream, the storybook wallpaper in Delphine’s house. A lot more is a matter of scriptwriting (Janet on the phone to Lucy, a deft piece of exposition), acting (Stoler’s shifting strategies for showing how Ray’s love for Martha transforms her, or her handling of Martha’s periodic, professional reversions to a bedside manner) and directing (the horrific murder of Janet).

Still more is attributable to Kastle’s desire to stick to the real facts about Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez as closely as possible. In an interview in Positif, he avowed that the only liberty taken with a story gleaned from newspapers and trial records involved the circumstances of the couple’s eventual arrest: it wasn’t ever established whether it was Martha or a neighbor who phoned the police, but Kastle decided to make it Martha “for dramatic reasons.” And the few period anachronisms –- mainly cars and long-playing record albums post-dating the late 1940s (coincidentally, the same period when “You Are Not I” was written) — offer no serious distraction from the film’s raw, concentrated focus.

Both these movies are about predators as well as victims, and it’s one measure of the success of each that it offers a compassionate glimpse of what it feels like to be on either side of the law (or fence). Each of Ray’s wives is presented as a recognizable type to be satirized and pitied, yet also appreciated and understood. The same paradox holds for Martha and Ray, whose powers and weaknesses are so intricately intertwined that we can never get to the bottom of what we think about them. In YOU ARE NOT I, Ethel and Sister may each greet the world with complacencies that we can’t quite accept, but Driver won’t let us totally reject them either. Like Martha and Ray, they are every bit as willful as the savage creative energies that bring them to life.