From the Chicago Reader (January 20, 1995). — J.R.

NOBODY’S FOOL

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Robert Benton

With Paul Newman, Jessica Tandy,

Bruce Willis, Melanie Griffith,

Dylan Walsh, Pruitt Taylor Vince,

Gene Saks, Josef Sommer,

and Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Since most Hollywood movies of the 90s offer unabashed fantasies, the hero’s success has become something of a given. Regardless of the odds against him (seldom her), one feels sure that he’ll emerge unscathed — triumphant over his enemies, often rolling in wealth, and with the lady of his choice at his side. Of course people often go to movies in order to bask in a universe of wish fulfillment, and most of our contemporary films are roughly akin to the fantasies of opulence and goodwill offered to Depression audiences 60-odd years ago (though it’s hard to think of many recent parallels, apart from a few TV docudramas, to Warner Brothers’ gritty, socially conscious melodramas of that period).

So when a Hollywood movie about failure comes along, it has the unexpected ring of authenticity: for all its sentimental safety nets, Nobody’s Fool looks and feels a good deal like much of U.S. life as it’s currently being lived: virtually everyone qualifies as an ornery fuck-up, complains incessantly about his or her lot, and sees no practical way out of life’s morass of everyday complications. Read more

Written as a column for the May-June 1977 Film Comment. Some of the details here are dated, I think, in an interesting manner — especially the discussion of “Disco-Vision”. I should add that the only version of MIKEY AND NICKY that had been released in the mid-70s was an unfinished edit by Elaine May that the studio had taken away from her and put out without her consent. -– J.R.

***

The world had gone crazy, said the crazy man in his cell. What was nutty was that the movie folk were trafficking in illusions in the real world but the real world thought that its reality could only be found in the illusions. Two sets of maniacs.

– Walker Percy, Lancelot

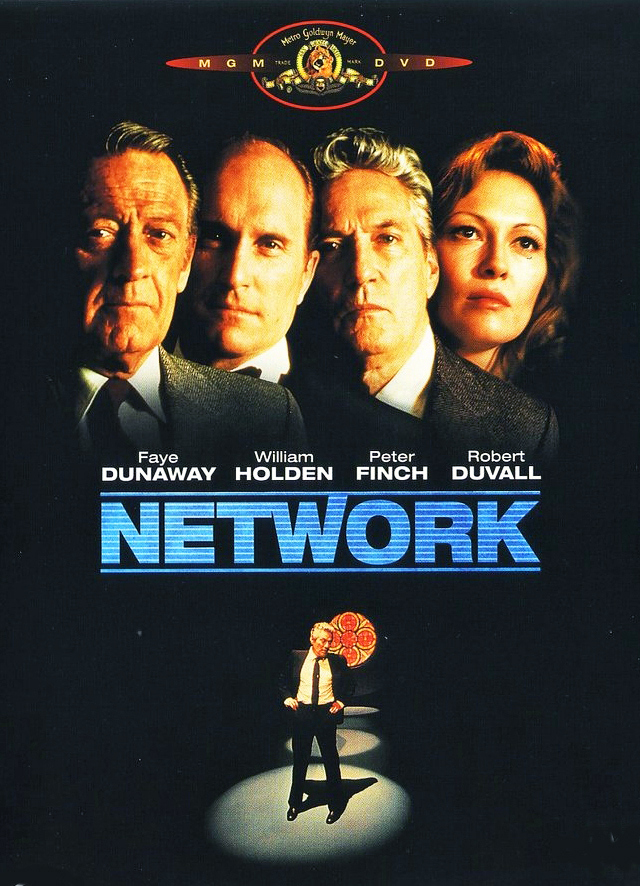

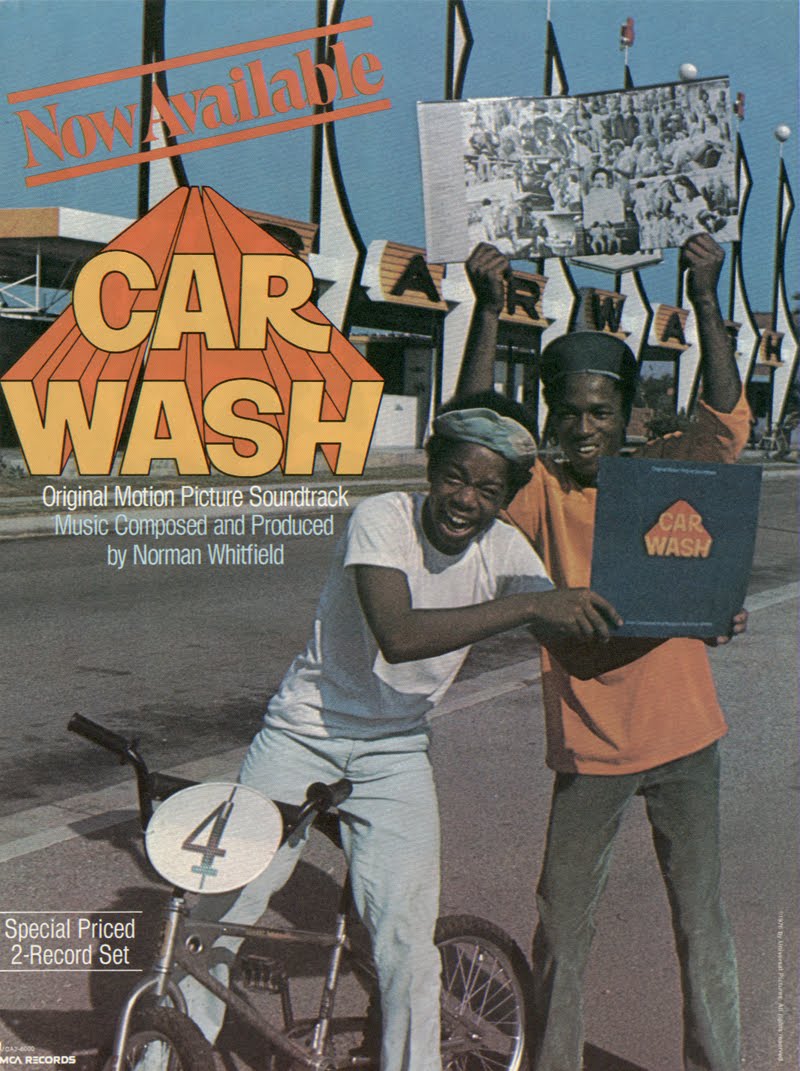

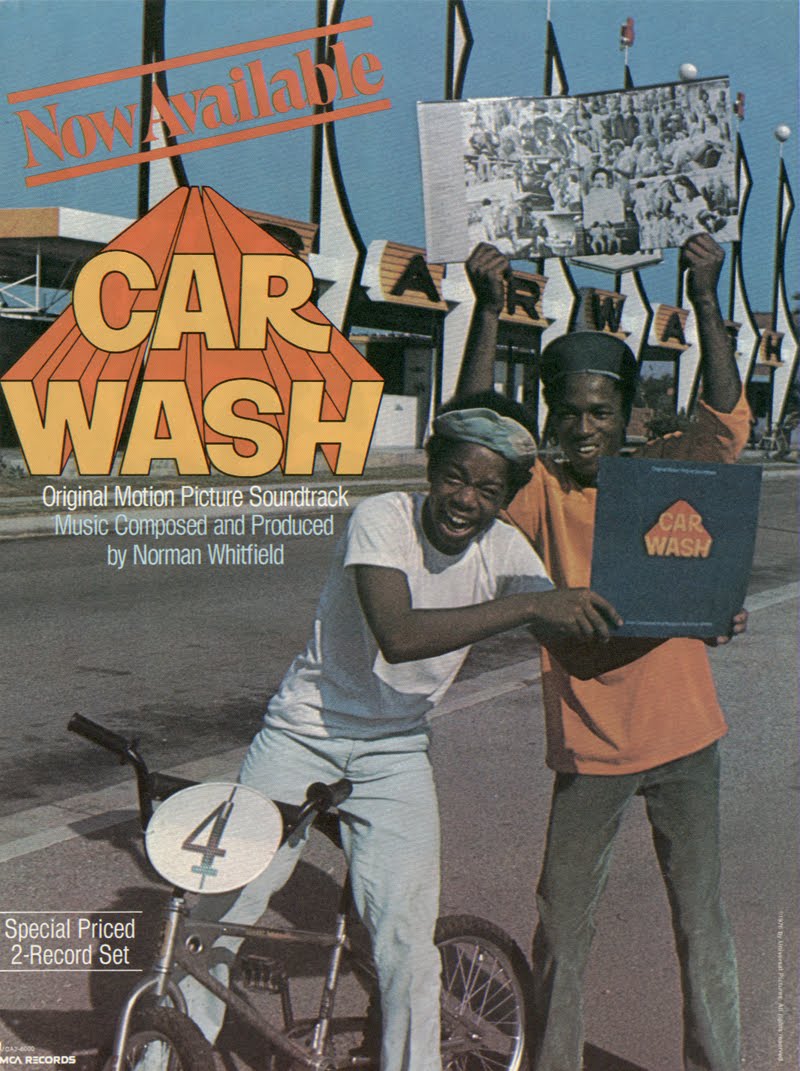

Compare the ads for NETWORK and CARWASH. The former conjures up a hot exposé, a “real” behind-the-scenes glimpse of What Goes On behind the moneyed façade of big-time broadcasting; the latter suggests a frivolous, “irresponsible” fantasy to be seen for fun, not edification. Moving back to the U.S. after over seven years abroad — a sudden shift from reflective Paris chrome and ashen London gray to La Jolla baby-blue, from cinema to some medieval state of pre-cinema or post-Cinema — the foreignness and familiarity of the country both seem epitomized by the absurdity of that cockeyed distinction, which virtually gets it all backwards. Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1977. — J.R.

U.S.A., 1968

Director: (not credited)

Dist–TCB. p.c–Drew Associates. For the Bell System. p–Robert Drew, Mike Jackson. assoc. p–Harry Moses. p. co-ordinator–Jean Swain. sc–(not credited). ph–Abbot Mills, Juliana Wang, Ralph Weisinger. asst. ph–Bill Hanson. In color. ed–Naomi Mankbwitz. m.d–Donald Voorhees. songs–fragments of “When the Saints Go Marching fn”, “Hello Dolly”, “Rose”, “The Kinda Love Song” by George Weiss, performed by Louis Armstrong; “Con Alma”, “Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac” performed by Dizzy Gillespie; “I’m in a Dancing Mood” performed by Dave Brubeck; “Light in the Wilderness” by Dave Brubeck; “Forest Flower”, performed by Charles Lloyd. sd–Dave Blumgart, Stan Agol. narrator–Don Morrow. with–Louis Armstrotrg, Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond, Joe Morello, Eugene Wright, Iola Brubeck, Matthew Brubeck, Michael Brubeck, Catherine Brubeck, Christopher Brubeck, David Brubeck, Darius Brubeck, Charles Lloyd, Keith Jarrett, Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody, George Weiss. 1,921 ft. 53 mins. (16 mm.).

Interviews with Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck and Charles Lloyd, interspersed with snatches of their music in rehearsal or performance.

An appalling example of how appreciation of jazz can be summarily crushed in the process of supposedly trying to promote the music, this American TV documentary follows the fatal course of rarely letting the music speak for itself for more than a few bars at a time, while encouraging each of the four musicians to pontificate at length about his life and art. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 1996); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Blush

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Li Shaohong

Written by Ni Zhen and Li

With Wang Ji, Wang Zhiwen, He Saifei, Zgang Liwei, Wang Rouli, Song Xiuling, Xing Yangchun, Zhou Jianying, and Cao Lei.

The use of multiple perspectives in Chinese painting was not for the purpose of making a hologram, nor was the use of parallel perspectives for the purpose of retaining the true dimensions of the objects represented. What was desired was rather a point of view which transcended that of the individual. The apparent horizon and vanishing point employed by Renaissance perspective made the image seem concrete, but demanded substantial identification with a particular viewer. Such images were perceived as both individual and momentary, seen by a particular person at a particular time. Chinese painting strove for a timeless, communal impression, which could be perceived by anyone, and yet was not a scene viewed by anyone in particular.

Chinese paintings did not portray reality; the world which the viewer entered was the realm of literature or philosophy, a realm which transcended nature. To enjoy a long tableau with small figures, one must shift one’s line of sight left and right, or up and down, a necessary condition for the appreciation of Chinese visual representation. Read more

This originally appeared in the May 23, 1997 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Children of the Revolution

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Peter Duncan

With Judy Davis, Sam Neill, F. Murray Abraham, Richard Roxburgh, Rachel Griffiths, Geoffrey Rush, Russell Kiefel, John Gaden, Ben McIvor, Marshall Napier, Ken Radley, Fiona Press, and Alex Menglet.

This cockeyed story is recounted by several narrators in pseudodocumentary style (a style distantly patterned on Warren Beatty’s in Reds): various old codgers in present-day Australia speak to the camera about the past, their accounts leading into several extended flashbacks. Judy Davis plays Joan Fraser, a red-diaper baby who learned about Karl Marx from her father when he took her fishing. In 1949 — during the darkest days of the cold war — she’s a young woman who still dreams of a workers’ revolution and still idolizes Joseph Stalin. When Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies decides that Australia should follow the U.S. into Korea and outlaw communism and sign various anticommunist treaties, Fraser goes ballistic: she gets herself and her boyfriend, Welch (Shine’s Geoffrey Rush), ejected from a movie theater by causing a commotion during a newsreel, decides it would be OK to go to prison (“What do you people want — a discreet revolution?”), Read more

From the Village Voice (October 10, 1974). — J.R.

Discriminations

A book by Dwight Macdonald

Grossman, $10

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Dwight Macdonald’s latest collection of articles is a sequel of sorts to his Politics Past — political-cultural and incidental literary criticism that composes a loose chronicle of the times, taking in a span of nearly five decades.

I blush a little to admit it today, but Dwight Macdonald was the first film critic I ever took seriously. He liked Citizen Kane, Breathless and Shadows and so did I, but I think the clincher was his prose — a rare kind of magazine writing, bursting with energy, that danced or sang or clowned regardless of what it was saying, with a fine ear for polemics and invective. This latter talent has gradually become known as his specialty. More humanistic and less of a school marm than John Simon and a lot more folksy and homespun than Gore Vidal, he shares with them the status of Master of the Chopping Block. (For the best whacks, see my favorite Macdonald collection, Against the American Grain [much of it recently reprinted, in 2011, as Masscult and Midcult: Essays Against the American Grain].) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 13, 1989). — J.R.

THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Lawrence Kasdan

Written by Frank Galati and Kasdan

With William Hurt, Kathleen Turner, Geena Davis, Amy Wright, David Ogden Stiers, Ed Begley Jr., and Bill Pullman.

Why is the inability to feel such a popular and respected subject in contemporary American movies? William Hurt makes his way through most of The Accidental Tourist, the new Lawrence Kasdan film based on Anne Tyler’s novel, like a human slug, devoid of energy, emotion, or much thought — a freeze-dried mass of nerveless inertia — and audiences appear to be cheering him on, as if there were something intrinsically noble about his condition.

A relatively serious, relatively realistic soap opera, The Accidental Tourist has scant stylistic or formal interest, so how one responds to it depends on how one responds to the story and characters. John Williams’s lush, romantic score asks us and evidently expects us to feel a great deal of tenderness toward its oatmeal hero, and I suspect that many members of the New York Film Critics’ Circle did, for they recently voted this movie the best of the year. But my main response was halfhearted respect (for the script and performances more than for the hit-or-miss direction) tinged with boredom, and a certain curiosity about what all the fuss was about. Read more

A book review published in the Village Voice (January 25, 1983). The version below restores some of the details deleted by an editor. — J.R.

JERRY LEWIS IN PERSON

By Jerry Lewis with Herb Gluck

Atheneum, $14.95

As a longtime Lewis fan who has lived in Paris, I have less curiosity about the French passion for him than most Americans. The unbridled sweep of the all-American ego at its most infantile and traumatized has always been an object of awe and fascination for the French; think of their celebrations of Poe and Faulkner, H.P. Lovecraft and Orson Welles. Call Jerry Lewis “America” (or vice versa) and you have a recognizable psychosexual object that signifies something more than slapstick and telethons. You also have an explanation for why some part of us despises the man — for rubbing our noses into potential traumas we claim to have outgrown, postulating his hysterical comedy as the literal cutting edge of our equilibrium.

One doesn’t ordinarily turn to an as-told-to show-biz memoir for extended self-analysis. But Jerry Lewis In Person exudes an uncomfortable candor that may actually endear Lewis to some of his detractors, while making admirers like me squirm a bit. The childhood sections which predictably dominate depict not only the lonely New Jersey misfit I expected, but also the street-smart chutzpah of a semi-abandoned tough guy who dreamt of murdering his grandfather, killed his cat in a rage when he was five, hated his show-biz parents for not even showing up to his bar mitzveh, and habitually socked anti-Semites and other wise guys (including his high school principal) in the mouth. Read more

This profile was published without title in the December 1983 issue of Omni, in a section simply called “The Arts”. -– J.R.

It makes perfect sense that Manuel De Landa, a thirty-year-old Mexican anarchist filmmaker who specializes in the aesthetics of outrage, inhabits a midtown Manhattan apartment so tidy and upstanding that it could almost belong to a divinity student. The point seems to be that if you want to shake the civilized world at its foundations, it helps your credibility if you wear a jacket and tie — especially if you speak with an accent that makes you sound like Father Guido Sarducci. For a talented artist who has an asocial image to sell and a highly social way of putting it across, it isn’t surprising that De Landa makes wild, aggressive films that leap all over the place while standing absolutely still. In The Itch Scratch Itch Cycle (1977) and Incontinence: A Diarrhetic Flow of Mismatches (1978),quarreling couples in tacky settings are subjected to all kinds of optical violence:The camera moves around them in the shape of a figure eight, or De Landa crazily cuts back and forth between two static shots of the principals screaming at each other — as if he were a mad scientist, controlling their shrieks with the twist of a knob. Read more

Published by Chicago’s a cappella press in 2000. The jacket reproduced below, which I prefer, belongs to the English edition published by Wallflower Press in 2002; the full title is Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See. — J.R.

To refer to a producer’s oeuvre is, at least to me, as ignorant as to refer to the oeuvre of a stockbroker.

— David Mamet

There are a lot of complaints these days about the declining quality of movie fare, and the worsening taste of the public is typically asked to shoulder a good part of the blame.

Other causes are cited as well. The collapse of the old studio system meant the loss of studio heads who lent their distinctive stamp to each of their pictures — often vulgar and overblown, to be sure, but also personal and engaged — to be replaced largely by cost accountants and corporate executives with little flair, imagination, or passion. The exponential growth of video has made home viewing more popular than theatrical moviegoing and has therefore helped to diminish everyone’s sense of what a movie is, so that the size and definition of the image, a clear sense of its borders, the quality and direction of light, and the notions of film as community event, theatrical experience, or “something special,” have all suffered terrible losses. Read more

From Slate (posted June 23, 2009). — J.R.

One of the key paradoxes of contemporary movie culture is that some film lovers claim that cinema is dying, others maintain that it’s entering a renaissance, and both factions are right. It all depends on whose movie culture you’re talking about.

The problem is how elastic and imprecise our terminology has become. Nowadays, when somebody says, “I’ve just seen a movie,” we don’t necessarily know whether the speaker saw it in a theater or on a mobile phone, alone or with a thousand other people, on celluloid or on a disc. These aren’t really the same experiences, even if we choose to call them all The Godfather or Up. And when it comes to distinguishing between film history and advertising, we may be even more confused.

One reason why we may be entering a renaissance in film viewing is that we no longer have to go to Paris or New York in order to learn anything comprehensive about the history of the medium as an art form. We can, in fact, live almost anywhere, at least if we own a multiregional DVD player — and nowadays one can acquire one of these for less than $50. Read more

Part of my 1987 application for the job of film reviewer at the Chicago Reader consisted of writing three long sample reviews for them in March and/or April — only one of which was published by them (Radio Days), although, as I recall, they paid me for all three. (Writing my pieces in Santa Barbara, I was limited in my choices of what I could write about.) I only recently came across the two unpublished reviews, of Platoon and Round Midnight, in manuscript, although I recall that I did appropriate certain portions of them in subsequent reviews. Otherwise, the first publications of these pieces are on this site. — J.R.

**PLATOON

Directed and written by Oliver Stone

With Charlie Sheen, Tom Berenger, Willem DaFoe and Keith David.

“I mean, you know that, it just can’t be done! We both shrugged and laughed, and Page looked very thoughtful for a moment. “The very idea!” he said. “Ohhh, what a laugh! Take the bloody glamour out of bloody war!”

Michael Herr, Dispatches

The myth of lost innocence that permeates American movies like some omnipresent air freshener ultimately has a lot to answer for. Read more

This book review appeared in the July 7, 1991 issue of Newsday. More recently (Christmas eve, 2014), I’ve read Susan L. Mizruchi’s instructive Brando’s Smile: His Life, Thought, and Work (Norton), which finds far more coherence in Brando’s career than Schickel did. — J.R.

BRANDO: A Life in Our Times, by Richard Schickel. Atheneum, 271 pp., $21.95

“Of the many illusions celebrity foists upon us the illusion of coherence, the senses that these are privileged people in the world who somehow know what they are doing in ways that we do not, is the largest, and possibly the most dangerous. But Marlon Brando has kept faith with his incoherence.”

Arriving at this judgment toward the end of a head-scratching appraisal of the logic and meaning of Marlon Brando’s career, critic Richard Schickel seems to be breathing a sigh of relief, and some readers may feel like joining him. It’s an honorable and instructive admission of defeat, and while one may disagree by finding some coherence where Schickel does not — I happen to relish Brando’s modest and earthy performance in The Freshman as a refreshing autocritique of his posturing role in The Godfather (which Schickel considers his last “real” performance) — it’s still a premise that one can hang an exploratory book on. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 20, 2004); I revised this slightly in June 2011. — J.R.

Revolution ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Stephen Jones

Written by Bob Avakian

With Avakian.

Queimada **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Gillo Pontecorvo

Written by Franco Solinas and Giorgio Arlorio

With Marlon Brando, Evaristo Marquez, Norman Hill, and Renato Salvatori.

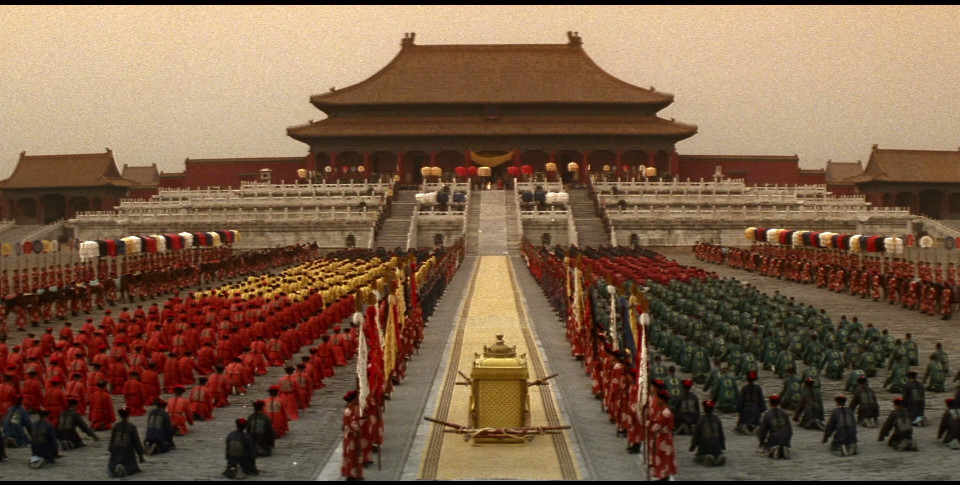

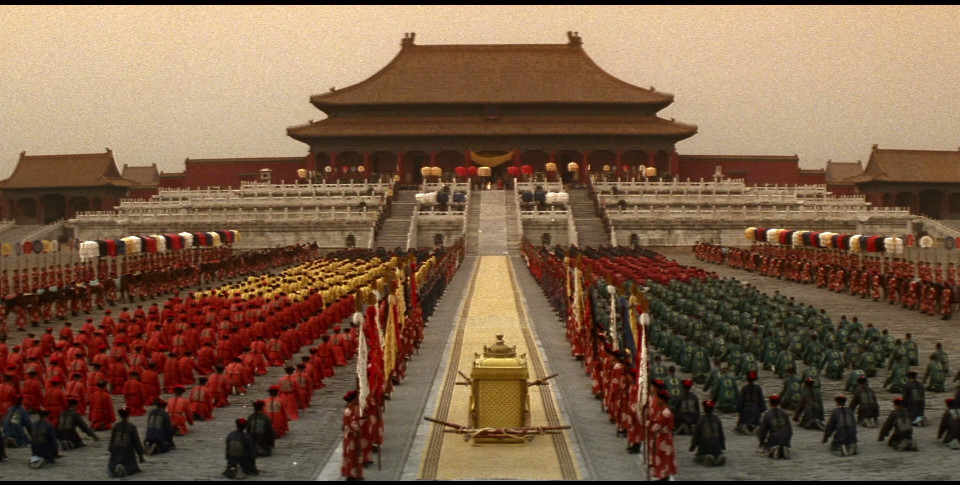

The Last Emperor **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Mark Peploe and Bertolucci

With John Lone, Joan Chen, Peter O’Toole, Ruocheng Ying, and Victor Wong.

August is traditionally the month when films people don’t know what to do with surface, a time when those films are less apt to be noticed. This August three of these films happen to be about revolution. Actually Revolution, showing Wednesday at the 3 Penny, isn’t a movie but a DVD of the first 136 minutes of a long, four-part lecture by Bob Avakian, chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party USA, in what is reportedly his first public appearance since 1979. The other two are director’s cuts of celebrated movies, both being screened here for the first time. Marlon Brando wrote in his autobiography that Gillo Pontecorvo’s Queimada (1969), showing several times this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, contains “the best acting I’ve ever done,” and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987), screening August 28 at Facets Cinematheque, won five Oscars, including those for best picture and best director. Read more

An unpublished essay written in June 1988 for the Chicago Reader. One of my few regrets about my 20 years at the Reader, unlike the year and a half I spent (1979-1981) at New York’s Soho News, was that whereas the latter allowed me to review books and movies concurrently, the Reader was interested in me only as a film reviewer, so any attempt to write about books for them was discouraged. I did make a point of reviewing two of Thomas Pynchon’s late novels for them (Vineland and Against the Day) –- having previously reviewed Gravity’s Rainbow for the Village Voice and having much later reviewed Mason & Dixon for In These Times between the two Reader reviews (all four of these reviews, incidentally, plus my earlier review of The Crying of Lot 49 for a college newspaper, can be accessed on this site).

I wrote the piece below on spec when Michael Lenehan was the paper’s editor and he told me I’d have to do a lot of rewriting before it could be published, so I bowed out. Read more