At Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna in the summer of 2015, Ehsan Khoshbakht and I launched a “Jazz Goes to the Movies” program, and reproduced below are our catalogue descriptions of what we showed. Late in June, Ehsan and I will be presenting a sequel to this program, with shorts featuring Duke Ellington.– J.R.

Jazz Goes to the Movies

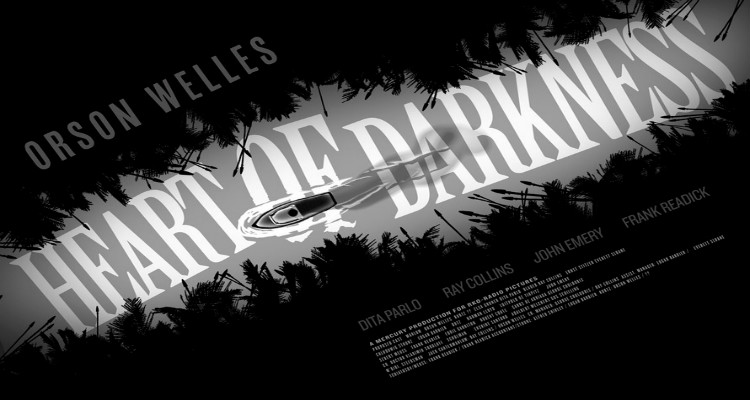

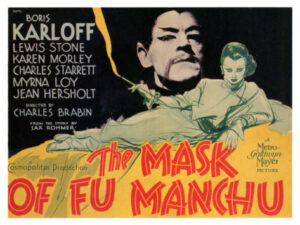

Now that jazz is no longer assumed to be automatically synonymous with decadence and the forces of darkness, it can finally be experienced and evaluated on its own terms, and we can begin to look back on a century-long partnership of jazz and film with a certain objectivity. Both are relatively new arts roughly contemporaneous with the 20th century, having grown out of socially disreputable origins and having fought for serious recognition.

Part of this partnership has yielded the “jazz film,” a subgenre basically devoted to the recording of performances. But there are also successful collaborations between the expressive possibilities of jazz and film. And the ways in which jazz has been used in movies invariably tells us a great deal about the social, ethnic, aesthetic, and cultural biases of diverse societies and periods. The various responses of film producers to integrated jazz groups in the thirties, forties, and fifties, provide a kind of thumbnail social history. Read more