From the Chicago Reader (November 1, 2007). For all its inventiveness and resourcefulness, I find the recent sequel too long and difficult to follow, but I love the appearances of Harrison Ford/Deckard and his dog. — J.R.

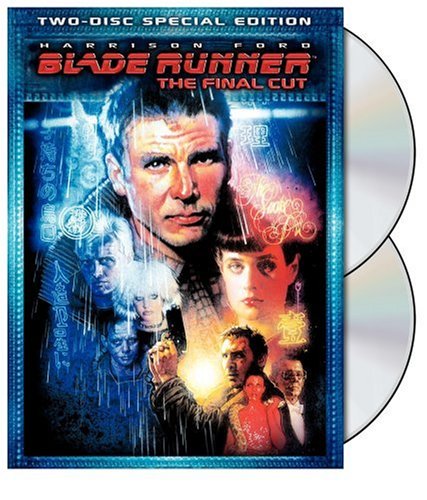

Blade Runner: The Final Cut |****

Directed by Ridley Scott

It took 25 years, but the makers of Blade Runner finally got it right. Preceded by at least six editions, five of them seen by the general public, this “final cut” is the optimal form of Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece. Neither a complex revision nor a simple restoration, it’s a retooling that presents the project as it was originally conceived. Although some of the violence has been intensified and stretched out, new footage isn’t really the point. The focus instead is on redressing technical errors and making other helpful adjustments, giving the film a fully comprehensible narrative. For the first time every detail falls into place.

Along with the equally pessimistic and misanthropic A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Blade Runner sets the standard for movies about androids in the post-Metropolis era. It presents a dark view of humanity where the artificial beings known as replicants (who tragically have a lifespan of just four years) command most of our sympathy. Like A.I., its roots lie in 19th-century literature — Frankenstein in this case, The Adventures of Pinocchio in A.I. — where mankind tries to produce an ideal version of itself, which suffers endlessly as a consequence.

Loosely derived from Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and set in 2019 Los Angeles, Blade Runner is especially memorable for its spectacular, intricately designed city views: monumental from above, smoky and rainy from below, extremely dense and cluttered on the street and indoors, and as charged with eroticism as an invented landscape of Josef von Sternberg. (The replicants outclass everyone as erotic objects.) Deckard (Harrison Ford), the neonoir cop hero, is forced out of retirement to hunt down and kill a band of replicants who’ve escaped from a slave ship in space. The mission grows more complicated when he falls in love with a seventh-generation replicant named Rachael (Sean Young), an experimental model implanted with human memories. There’s also the likelihood that Deckard is a replicant himself. The whole violent tale can be read as a parable in which robot slaves, all mentally and physically superior to those who create and command them, are forced to destroy one another. (Deckard’s bond with Rachael is sealed when she saves his life by shooting another replicant.)

Blade Runner’s long journey from commercial flop to cult classic is a complicated, slapstick saga. All but this most recent chapter is recounted in Paul M. Sammon’s exhaustive Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner (1996).

In 1989 a sound reconstruction consultant named Michael Arick discovered a 70-millimeter work print of Blade Runner that had been shown at a sneak preview in Denver coincidentally on the same day (March 5, 1982) Philip K. Dick’s body was being cremated in Santa Ana. (It screened again in Dallas the next day.) At this point, the film had neither a voice-over (apart from one brief segment) nor a happy ending, and the mixed audience response persuaded Warner Brothers to add both. The new ending was furnished with outtakes from the opening sequence of The Shining.

When director Ridley Scott saw this work print in 1990, he proposed releasing a “cleaned-up” version as a director’s cut. But he was too busy just then with Thelma & Louise to supervise the work himself. A few months later he tried unsuccessfully to buy the print from Warner Brothers. By this time, the studio had screened the 70-millimeter print as well as a 35-millimeter dupe in Los Angeles. Billed as “The Original Director’s Version,” it met with much commercial success.

When Scott became aware of this, he left preproduction work on 1492 in London and flew to LA to propose a proper director’s cut. Two separate versions were then set in motion — one in London by Arick, who followed Scott’s detailed instructions, the other in LA by Warner employee Paul Gardiner, who had a much more rudimentary revision in mind and was apparently unaware of Arick’s work. Scott was so distracted by 1492 that he wound up approving Gardiner’s version instead of Arick’s.

It turned out that both versions lacked a couple of shots of a unicorn that Scott considered more important than any other detail. The unicorn appears to Deckard in a dream, and provides an early hint that he might be a replicant. When Scott discovered the omission, he threatened to place an ad in trade papers disowning Blade Runner: The Final Director’s Cut (as it was then called). Warner Brothers agreed to bring Arick back to edit a third version within a month. This one ignored most of Scott’s previous specifications but did eliminate the voice-over and happy ending and included at least one shot of a unicorn, pulled from an outtake. Until now, this version has been called the “director’s cut,” an object lesson in how we should view that term with some skepticism. But as the film’s 25th anniversary approached, Scott was finally provided the opportunity to produce a cut for rerelease that actually fits that description.

Ironically, I’ve always retained some affection for the voice-over and ending of the 1982 version. But Scott has finally managed to tell the story more clearly, making all the small fixes he’s spent years fighting for, and the effort has been entirely worth it. Better late than never.