Based on feedback, I would guess that this article, which first appeared on June 25, 1998, is the most popular piece I ever published in the Chicago Reader. Although it’s been featured as a separate item for several years on their site, I noticed that, thanks to some of their recent user-unfriendly retoolings of that site — which makes it much harder to access anything and everything, including this article — my own list of my 100 favorite films at the end of this piece and the AFI’s list of the supposedly greatest 100 films somehow got scrambled together. [Update, 7/25/09: Checking back a day later, this now appears unscrambled.] This is mainly why I’ve decided to reprint the original piece here in Notes, with only a few minor modifications. I revised and expanded this piece still further in my book Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, where it forms the sixth chapter. (I’m sorry that the English edition of this, which has a much better jacket, has become more scarce.) One of the main additions, on page 93, is a list of the 25 titles on the AFI list that I probably would have included on my own if I hadn’t wanted to create an all-new list for polemical purposes; six of these titles are illustrated at the tail-end of this piece.

My subsequent list of my 1000 favorite films from everywhere appears in the back of my book Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons, and this in turn was expanded and updated for the book’s paperback edition. –J.R.

List-o-Mania

Or, How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love American Movies

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Just about everyone I’ve spoken to regarding the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 greatest American movies — presented on a stultifyingly vacuous three-hour CBS special last week — has been depressed about it, in a hang-dog sort of fashion. Part of this is the lackluster list itself and part is the absolute failure of the show to offer anything resembling an interesting justification of any of the titles that got picked. But it’s not at all the sort of deflation that comes when outsized hopes are dashed. Rather, it’s a kind of grim acknowledgement that what we call “business as usual” these days automatically follows a law of diminishing returns, yielding an increasing dumbing down of film culture that outpaces our already shrinking expectations. “Of course it’s going to keep getting worse and worse,” we all seem to be assuming, and then it gets to be even worse than we imagined.

Is the list simply a brute commercial ploy dreamed up by a consortium of marketers to repackage familiar goods, or is it a legitimate cultural intervention that’s somehow supposed to improve the quality of our lives? For that matter, are we still capable of distinguishing between the two? If it’s the former, then surely it qualifies as front-page news only if we’re living in the equivalent of Stalinist Russia. If it’s the latter, then why does the list contain so many movies that lie — movies that lie about Vietnam (The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now), about racism (The Birth of a Nation, Taxi Driver, Pulp Fiction), about countless other matters? Why are so many of the entries aesthetically bland or worse while recapitulating all the worst habits of Hollywood self-infatuation, liberal (Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner) as well as conservative (Forrest Gump)? Shane to my taste is already bad enough, but why did Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid have to make the cut as well, along with (choke) Dances with Wolves? I yield to no one in my love for James Cagney, but did he ever make a less bearable picture than Yankee Doodle Dandy, the only one on the list?

But let’s stop and consider what we’re working with. Unlike every other comparable national institution on the globe, which considers world cinema of national importance, the American Film Institute restricts its focus to films of its own nationality. (The organization was launched during the Johnson administration, at a time when patriots must have been concerned about Americans seeing too many foreign pictures.) This means that a mere survey of the best 100 movies, full stop, is a lot more than the AFI can handle, and a recycling of already overtouted product has to be delivered to our doorsteps all over again, just to prove what fine citizens we are. To make matters worse, as Michael Wilmington recently pointed out in the Tribune, “The battle-weary NEA, which used to supply The AFI with several million dollars in annual grants now gives about $100,000. By contrast, Britain supports its own Film Institute to the tune of over $60 million a year.”

Yet on reflection, whether the AFI can justify getting even two cents on its present agenda is doubtful in my opinion. I’m told that when they recently shut down their art theater at the Kennedy Center in Washington, the AFI’s director, Jean Firstenberg, said to the press that video made repertory programming unnecessary; if that’s what she said and that’s what she meant, I’d rather see the same funds used to reduce the AFI to rubble. Given its egregious industry ass-kissing throughout its existence, I’m tempted to conclude that the AFI’s only substantial contribution to film culture — American or global — is the fact that David Lynch’s Eraserhead was produced at its film school.

But the malaise I’m talking about, provoked by the aforementioned list of 100 movies, isn’t just a response to the long-term uselessness of the AFI; it’s about the increasing lack of any viable distinction between what used to be called Public Works and corporate greed. Whether in the present circumstances this has grown out of a holy or unholy alliance between the AFI, Blockbuster Video, CBS, TNT, Turner Classic Movies, and the home video divisions of 13 film studios — all of which have planned a summer full of jolly hooplah around this tacky list to promote their joint efforts — doesn’t really matter. What does matter is the rise of corporate cultural initiatives bent on selling and reselling what we already know and have, making every alternative appear more scarce and esoteric, and not even attempting to expand or illuminate the choices made in the process. (As an academic friend points out, it’s almost as if most of the masterpieces in the Louvre were cleared out to make room for the work of Sunday painters.)

Let me hasten to add that if I were drawing up my own list of the 100 greatest American movies from scratch, roughly a quarter of the AFI’s list would be on it. But because I’m writing for an alternative newspaper, it seems more useful to offer an alternative list of 100 features rather than an unwieldy composite of the 25 or so AFI titles I can live with and 75 others. I’ve also decided to list my choices alphabetically rather than impose any kind of order based on merit, which would be tantamount to ranking oranges over apples and declaring Wednesday superior to Monday. For if these lists have any purpose at all from our standpoint (as opposed to the interests of the merchandisers), this is surely to rouse us out of our boredom and stupor, not to ratify our already foreshortened definitions and perspectives. Above all, the impulse to provide another list is to defend the breadth, richness, and intelligence of the American cinema against its self-appointed custodians, who seem to want to lock us into an eternity of Oscar nights. And the most salient fact about my own list is that it’s far from exhaustive; I haven’t even found room on it for such miracles as Adam’s Rib, The Band Wagon, The Bitter Tea of General Yen, Blonde Crazy, John Ford’s Cavalry trilogy, Crumb, Dog Day Afternoon, Duel in the Sun, Family Plot, Gun Crazy, Ice, Lives of Performers, Me and My Gal, The Old Dark House, Paths of Glory, Pickup on South Street, Point of Order, Rope, Ruggles of Red Gap, Safe, Salt of the Earth, Two Lane Blacktop, and God knows what else.

For all the ranting and raving I do about the absence of foreign movies from American screens — exacerbated by the fact that the only American cable channel to show many of them, BRAVO, systematically recuts them all — I have to admit that of all the national cinemas I know, the American cinem is almost certainly the richest. That’s what makes the historical and aesthetic paltriness of the AFI list so stupefying; the net effect appears to be the taste of viewers who can’t remember what they saw beyond a few years back, and then mainly what they saw on video. Given the stringent limitations placed on what kind of American movies can be financed, made, exhibited, and marketed today, it’s especially poignant that a brilliant industry aberration like Citizen Kane should head the AFI list, just as it’s headed every comparable list over the past 30-odd years — a movie that clearly couldn’t get bankrolled today (it’s in black and white), much less survive test-marketing previews, and which failed to turn a profit when it came out. The persistence of Kane as a favorite is ample proof, if proof were ever needed, that viewers — even “film professionals” — are smarter than they’re usually cracked up to be. (Kane was the first of Orson Welles’ Hollywood films, and one reason why I’ve refrained from including his last, Touch of Evil, on my own list is my personal involvement as consultant on a new version, re-edited according to Welles’ instructions, scheduled to open in the fall.)

Where viewers are perhaps less smart is in rooting out most of the other American masterpieces that currently have less mainstream visibility — ones that require some alertness to what plays fleetingly at alternative venues and the sort of initiative that’s needed to get to them. The lax attitude that “anything” can eventually be caught up with on video is a debilitating illusion — not only because it’s literally untrue, but also because none of these masterpieces was ever designed to be seen that way, any more than any great novel was ever written in order to be skimmed or read with various pages torn out. So if you want to test my list against the AFI’s, this week offers a perfect opportunity because two of “their” favorites (From Here To Eternity and Forrest Gump) and two of mine (Rio Bravo and Tom Tom the Piper’s Son) are all playing at alternative venues in Chicago this week. But if you decide to catch Tom, Tom on video at a future date instead you’ll be out of luck, because what that pungent silent experimental film does would lose most of its meaning and impact on video even if its maker, Ken Jacobs, were foolish enough to authorize a transfer. (corrective postscript, 2009: Tom Tom the Piper’s Son has subsequently come out on VHS in France, on the excellent Re:Voir label, and it doesn’t look bad at all.)

Admittedly, Tom Tom the Piper’s Son is one of the most difficult films on my list, so I wouldn’t recommend it to everyone (just as I wouldn’t recommend Kane to all my women friends). It’s one of my three selections that both incorporate and critically analyze other films, along with the otherwise quite different Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (a superb hour-long essay film by Thom Andersen, made in 1974 and narrated by Dean Stockwell) and That’s Entertainment! III (a work of critical historiography as well as an excellent compilation that was rudely dumped by its distributor in 1994.)

The vicissitudes of availability (read: access) always play a major role in developing film tastes and canons, and if the AFI and its business cronies had wanted to do something genuinely useful, they might have polled the same group of individuals about the 100 most neglected America movies and then made an effort to make them available, on film and on video. I can’t say I’d agree with all the results, and, as I’ve already suggested, some of the most neglected films are experimental works that wouldn’t work on video anyway. But it’s emblematic of how far we are from any reasonable film culture that, even if the AFI and company had elected to make the first ten or 25 films on its own list available in new 35-millimeter prints, to be shown in theaters across the country, a veritable revolution would have to occur in the studios to make such an occurrence possible.

***

Being landlocked is a major part of the problem. Twenty -one years ago, I participated in a similar “revaluation” of American cinema conducted by the Royal Film Archive of Belgium that polled 116 Americans and 87 non-Americans from two dozen countries. The results, contained in a fascinating volume called The Most Important and Misappreciated American Films Since the Beginning of Cinema, were much more substantial and lively, and not only because the 1925 Ben-Hur garnered more votes in that survey than the 1959 version. (Truthfully, I haven’t seen either, but at least the silent version piques my curiosity.) Thirty-six movies in the AFI list made it into the RFA’s top 100, and Citizen Kane topped both lists. But even after one takes into account the 15 titles in the AFI list made since 1977 (the year of the RFA survey), the differences are extremely telling. The films in the RFA list that came in second, third, and fourth — Sunrise, Greed, and Intolerance — don’t figure at all in the AFI pantheon, and not far below those essential works were movies by such key figures as Robert Flaherty, Buster Keaton, King Vidor, Ernst Lubitsch, Victor Seastrom, Preston Sturges, and Josef von Sternberg, all unrepresented in the AFI’s corny hit parade.

Should one snobbishly conclude from this that non-Americans are necessarily more intelligent and discerning when it comes to American movies? I wouldn’t. It’s important to bear in mind that the RFA polled 203 film professionals — historians, critics, archivists, directors, teachers, and even a few students — whereas the AFI polled over 1500 Americans of every conceivable stripe in terms of their knowledge about film. (If memory serves, I was one of them.) One should add that the RFA’s and the AFI’s notions of what a “film professional” is couldn’t be more disparate: in this country, where familiarity with film history rarely plays any role in the hiring of reviewers, “film professionals” tend to get defined in tautological terms as people who write about films. (Combined with institutional validation, this produces all sorts of strange anomalies — such as the process by which, say, Pauline Kael and Daphne Merkin might be regarded as sisters under the skin.) The differences between Americans and non-Americans in judging American movies are basically matters of access and cultural conditioning — not taste or intelligence in isolation from these factors — and the consequences of these differences can be staggering.

Let me cite a couple of examples of what I mean, both drawn from very recent experience. Two nights before I tried to watch the AFI’s three-hour special, I was in a hotel room in downtown Helsinki, having just returned from the four-day Midnight Sun International Film Festival in Lapland, and when I did some channel-surfing, I found two films playing on Finnish TV, both in pristine prints–Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries and Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du lac. When I mentioned this the next morning to Peter von Bagh, director of the Midnight Sun Festival, he was miffed that the local TV programmers were so thoughtless that they could screen both films at once, meaning that local film buffs couldn’t tape both of them.

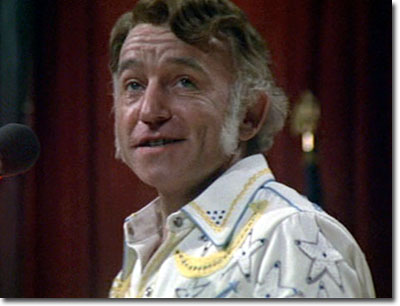

Another example, four days earlier: When I arrived on a bus with the other guests at Sodankyla — the remote village in the Arctic Circle where the Midnight Sun Festival has been held since its inception 13 years ago — the first thing I saw on the main street was a couple of new street signs that said, “Samuel Fuller’s Street”. An hour later, von Bagh — a professional film historian who was one of the 87 non-Americans polled by the RFA in 1977 — was officially and permanently renaming the street at an impromptu ceremony. For those who need to know, Fuller is a major Hollywood filmmaker who died last November and is unrepresented not only in the AFI’s top 100, but also in its top 400 (though he gets two slots in my list); he attended the festival its first year and subsequently starred in Tigrero, a film made by one of the festival’s cofounders, Mikka Kaurismaki. This year, the festival showed a feature-length documentary about Fuller, Fuller’s Underworld, U.S.A., and Tigrero as well. And given the force and complexity of what Fuller’s films had to say about American racism from the early 50s onwards, it was more than a little disconcerting to fly back to Chicago, turn on the TV, and hear Jack Valenti praise the mediocre and relatively gutless To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) — number 34 on the AFI list — as the first Hollywood film to deal honestly with racial issues. It made me wonder if Valenti had been living on the moon; if so, he might have rocketed down to the Arctic Circle for some enlightenment.

Robert Mulligan, who directed To Kill a Mockingbird, is a talented filmmaker, but better pictures by him would have found their way onto the list if his mise en scène were the issue. One can safely bet that the inclusion of To Kill a Mockingbird — like the preference for Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner over the infinitely superior Tracy-Hepburn vehicle Adam’s Rib — is merely a function of the kind of liberal self-congratulation that brings standing ovations to Oscar nights and tears to Valenti’s eyes. It has nothing to do with either the art of cinema or the reality of America — check out The Phenix City Story if you want to learn something about Alabama, as opposed to Gregory Peck’s virtue — but a great deal to do with the industry’s guilty conscience. Indeed, what the AFI in one of its press releases has called a “celebration of the 100th anniversary of American movies” reminds me of Haven Hamilton’s glib country-western national anthem at the beginning of Robert Altman’s Nashville: “We must be doing something right to last 200 years.” I would submit that if this piss-poor representation of the best that American cinema can do is all we have to celebrate, we must be doing something wrong.

***

One proof of how landlocked we are is the inclusion on the AFI list of British films like Lawrence of Arabia (no. 5), The Bridge on the River Kwai (no. 13), Doctor Zhivago (no. 39), The Third Man (no. 57), and, more arguably, A Clockwork Orange (no. 46) — a gesture no doubt of unconscious imperialism on the part of those polled, apparently justified by the tentacles of American finance and/or a few Hollywood actors. (Why The Third Man turns up according to these rules but not The Thief of Bagdad is anyone’s guess. But in part as a riposte to A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick’s most dubious feature, I’ve included Andy Warhol’s remarkable adaptation of the same English novel, Vinyl, on my own list.)

Last summer, for a retrospective of “neglected” American movies selected by American directors held at the Locarno film festival, Steven Spielberg had either the cheek or the innocence to select Lawrence of Arabia — a neglected American movie if there ever was one. But back in 1977, only four stray participants in the RFA survey thought to include any of the David Lean films cited above, three of whom were American (and one of whom was a member of the AFI’s board of trustees), and not one of the 203 had the nerve to select The Third Man. So maybe a gradual slippage in our understanding of what is and isn’t American is part of the trouble. For my own list, I’ve grappled long and hard with the existential issue of national identity posed by such ambiguous masterpieces as F. W. Murnau’s Tabu, Luis Buñuel’s The Young One, Albert Lewin’s Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, Josef von Sternberg’s The Saga of Anatahan, Michael Snow’s Wavelength and Back and Forth, and David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, and have finally wound up excluding all of them because of my serious doubts.

Rightly or wrongly, I’ve also refrained from including some of my favorite films by high-profile directors who are well represented on the AFI list, even if their best films aren’t. For the record, I prefer The King of Comedy to Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, The Conversation to either of the Godfathers, and Dumbo to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Fantasia; but even though I had some regrets about excluding these favorites, I have no doubt that readers can find them without my prodding. (Though one might quarrel with me excluding animation features entirely from my list — just as I would quarrel with the absence of independents like Cassavetes and experimental filmmakers like Brakhage from the AFI’s — I would argue that the most remarkable animation in American cinema, from Tex Avery to Robert Breer, is generally found in short films. For that matter, the absence of shorts as an arbitrary ground rule is what explains my exclusion of Maya Deren as well.)

I’ve deliberately sought to make my list conservative rather than provocative, and grounded in pleasure rather than any dutiful sense of historical importance. But since I’ve already stressed the significance of access and cultural conditioning in forming tastes, I should clarify the nature of my own background, which inevitably slants my list in a particular direction. Twenty-five of my selections were released in the 50s, while I was growing up, and my acquaintance with American cinema was based on two atypical forms of access that determined my cultural conditioning. The first came from being the grandson of a man who ran a chain of movie theaters in Alabama and the son of a man who worked for the chain, which meant that I had virtually unlimited access to Hollywood movies throughout most of the 50s, seeing practically everything that came out without having to pay admission. And the second form of access came from living in Paris and London between 1969 and 1977, when the American movies I saw in both places — bolstered in Paris by the Cinémathèque and numerous revival houses, and in London by the British Film Institute, where I was an employee — were not always the same things that one could see in New York and Chicago. And apart from this kind of access, the criticism I was reading in both cities was re-educating me on the subject of American movies, because French and English critics were discovering important things about these movies that my cultural conditioning in Alabama didn’t reveal. Discoveries of this kind are still going on across the world, illuminating certain aspects of American film history that we’re still catching up on — though we might never pick up on the signals if all we’re listening to is the American film industry and its deputies.

Am I saying that the 50s were the most plentiful decade in American movies? That’s what my own access and cultural conditioning tells me, because what I find there, in spite of all that period’s repression — and maybe in part because of it — is an unparalleled grappling with this country’s social reality that other decades, including the present one, can’t begin to match. But I can easily imagine a critic like Manny Farber who grew up during the 30s making an equally strong case for that decade; and a more recent generation of critics who grew up during the 70s — including Kent Jones in the U.S., Nicole Brenez in France, Alexander Horwath in Austria, and Adrian Martin in Australia — have recently been offering some powerful arguments on behalf of American movies from that era. (For the record, I’ve wound up including 16 films from the 70s, 15 from the 40s, 14 from the 30s, 11 from the 20s, and 10 from the 60s, whereas the teens, 80s, and 90s get only token representation.)

In the final analysis, selecting America’s 100 greatest movies has to be an ongoing, perpetual activity of exploration and discovery — something that can only happen if we stop to consider what we still don’t know about the subject and try to set up some channels for educating ourselves. The sad news about the AFI’s version is that it proposes we stop looking, go home, and proceed to pick more lint out of our navels for the remainder of the millennium.

Rosenbaum’s Alternate 100:

Ace in the Hole/The Big Carnival (1951)

An Affair to Remember (1957)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Avanti! (1972)

The Barefoot Contessa (1954)

Bigger Than Life (1956)

The Big Sky (1952)

The Black Cat (1934)

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

Broken Blossoms (1919)

Cat People (1942)

Christmas in July (1940)

Confessions of an Opium Eater (1962)

The Crowd (1928)

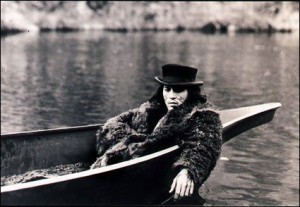

Dead Man (1995)

The Docks of New York (1928)

Do the Right Thing (1989)

Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (1974)

11 x 14 (1976)

Eraserhead (1978)

Foolish Wives (1922)

Force of Evil (1948)

Freaks (1932)

The General (1927)

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953)

Gilda (1946)

The Great Garrick (1937)

Greed (1925)

Hallelujah, I’m a Bum (1933)

The Heartbreak Kid (1972)

Housekeeping (1987)

The Hustler (1961)

Intolerance (1916)

Johnny Guitar (1954)

Judge Priest (1934)

Killer of Sheep (1978)

The Killing (1956)

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976)

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

The Ladies’ Man (1961)

The Lady From Shanghai (1948)

Last Chants for a Slow Dance (1977)

Laughter (1930)

Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948)

Lonesome (1929)

Love Me Tonight (1932)

Love Streams (1984)

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

Make Way for Tomorrow (1937)

Man’s Castle (1933)

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

Mikey and Nicky (1976)

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

My Son John (1952)

The Naked Spur (1953)

Nanook of the North (1922)

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

The Nutty Professor (1963)

The Palm Beach Story (1942)

Panic in the Streets (1950)

Park Row (1952)

The Phenix City Story (1955)

Point Blank (1967)

Real Life (1979)

Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1971)

Rio Bravo (1959)

Scarface (1932)

The Scarlet Empress (1934)

Scarlet Street (1945)

Scenes From Under Childhood (1967)

The Scenic Route (1978)

The Seventh Victim (1943)

Shadows (1960)

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

The Shooting (1967)

The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

The Sound of Fury/Try and Get Me! (1950)

Stars in My Crown (1950)

The Steel Helmet (1951)

Stranger Than Paradise (1984)

The Strawberry Blonde (1941)

Sunrise (1927)

Sylvia Scarlett (1935)

The Tarnished Angels (1958)

That’s Entertainment! III (1994)

This Land Is Mine (1943)

Thunderbolt (1929)

Tom Tom the Piper’s Son (1969)

To Sleep With Anger (1990)

Track of the Cat (1954)

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Vinyl (1965)

Wanda (1971)

While the City Sleeps (1956)

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957)

Woodstock (1970)

The Wrong Man (1957)

Zabriskie Point (1970)

Appendix:

American Film Institute’s Top 100

1 Citizen Kane (1941)

2 Casablanca (1942)

3 The Godfather (1972)

4 Gone With the Wind (1939)

5 Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

6 The Wizard of Oz (1939)

7 The Graduate (1967)

8 On the Waterfront (1954)

9 Schindler’s List (1993)

10 Singin’ In The Rain (1952)

11 It’s A Wonderful Life (1946)

12 Sunset Boulevard (1950)

13 The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

14 Some Like It Hot (1959)

15 Star Wars (1977)

16 All About Eve (1950)

17 The African Queen (1951)

18 Psycho (1960)

19 Chinatown (1974)

20 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

21 The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

22 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

23 The Maltese Falcon (1941)

24 Raging Bull (1980)

25 E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982)

26 Dr. Strangelove (1964)

27 Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

28 Apocalypse Now (1979)

29 Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

30 The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948)

31 Annie Hall (1977)

32 The Godfather Pt. II (1974)

33 High Noon (1952)

34 To Kill A Mockingbird (1962)

35 It Happened One Night (1934)

36 Midnight Cowboy (1969)

37 The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

38 Double Indemnity (1944)

39 Doctor Zhivago (1965)

40 North By Northwest (1959)

41 West Side Story (1961)

42 Rear Window (1954)

43 King Kong (1933)

44 The Birth of a Nation (1915)

45 A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

46 A Clockwork Orange (1971)

47 Taxi Driver (1976)

48 Jaws (1975)

49 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

50 Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

51 The Philadelphia Story (1940)

52 From Here to Eternity (1953)

53 Amadeus (1984)

54 All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

55 The Sound of Music (1965)

56 M*A*S*H (1970)

57 The Third Man (1949)

58 Fantasia (1940)

59 Rebel Without a Cause (1955)

60 Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

61 Vertigo (1958)

62 Tootsie (1982)

63 Stagecoach (1939)

64 Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

65 The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

66 Network (1976)

67 The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

68 An American in Paris (1951)

69 Shane (1953)

70 The French Connection (1971)

71 Forrest Gump (1994)

72 Ben-Hur (1959)

73 Wuthering Heights (1939)

74 The Gold Rush (1925)

75 Dances With Wolves (1990)

76 City Lights (1931)

77 American Graffiti (1973)

78 Rocky (1976)

79 The Deer Hunter (1978)

80 The Wild Bunch (1969)

81 Modern Times (1936)

82 Giant (1956)

83 Platoon (1986)

84 Fargo (1996)

85 Duck Soup (1933)

86 Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

87 Frankenstein (1931)

88 Easy Rider (1969)

89 Patton (1970)

90 The Jazz Singer (1927)

91 My Fair Lady (1964)

92 A Place in the Sun (1951)

93 The Apartment (1960)

94 Goodfellas (1990)

95 Pulp Fiction (1994)

96 The Searchers (1956)

97 Bringing Up Baby (1938)

98 Unforgiven (1992)

99 Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967)

100 Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)