This synopsis and review appeared in the December 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin.

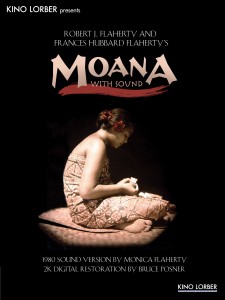

I’ve only just begun to familiarize myself with Moana with sound (see first still below), put together by the Flahertys’ daughter Monica, restored by Bruce Posner and Sami van Ingen (the Flaherty’s great-grandson), and posthumously released on Blu-Ray today by Kino Lorber. But I’ve already sampled enough of it — as well as all of Posner’s “short” (39-minute) history of the project, included along with other extras on the Blu-Ray — to view it as a major achievement, hopefully leading to a major reassessment of what I regard in some ways as Flaherty’s most neglected masterpiece. — J.R.

Moana

U.S.A., 1925

Directors: Robert J. Flaherty, Frances Hubbard Flaherty

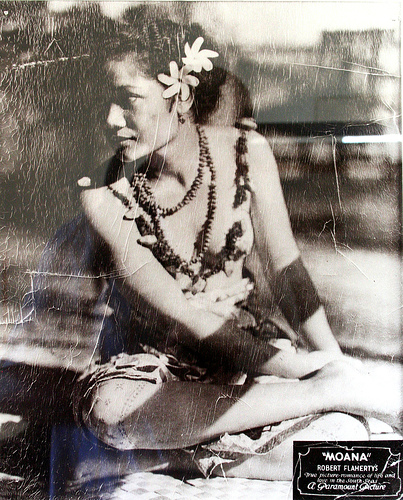

Savai’i, a Samoan island. Near the village of Safune, Moana pulls taro root from the ground and peels it while his betrothed Fa’angase bundles leaves, his mother Tu’ungaita carries mulberry sticks and his younger brother Pe’a helps them. Setting off for the village, they set a trap for wild boar, the forest’s only dangerous animal, which they subsequently capture. Moana, Fa’angase, and Pe’a go spear-fishing, along with Moana’s older brother Leupenga. Back in the village, Tu’ungaita makes back-cloth for a lavalava, a native dress. Pe’a binds his feet together and climbs a tree for coconuts, then starts a fire with coconut shells on the beach to cook a “robber-crab”. The group wrestle with a giant turtle and load it into their canoe; Fa’angase eats live fish. In the village. Tu’ungaita prepares a meal. Moana is anointed with oil before performing the siva dance with Fa’angase. Preparations are made for Moana’s tattooing by the tufunga (tattooer) and the villagers, and then the ceremony takes place. The village chief drinks kava and the dancing continues. In their hut, Moana’s father Tama and Tu’ungaita watch Pe’a sleeping; outside, Moana and Fa’angase perform their lively dance of betrothal.

“Moana,” wrote John Grierson is 1926, “being a visual account of events in the daily life of a Polynesian youth, has documentary value”, thus translating the French term documentaire and launching a category which is still said to apply to the film fifty years later. The irony is that Moana (“the sea” in Samoan) is in fact a fictional film in many of its particulars; even the members of the central “family” are not all related to one another, having been selected for their photogenic qualities and thespian talents rather than their blood ties. Recalling that Nanook of the North, Flaherty’s only previous film, begins with that most familiar of circus acts –- an Eskimo family emerging from the interior of a canoe like a profusion of clowns from an overstuffed car –- it becomes clear that Godard’s dictum about theatre and documentary being inextricably involved with one another is basic to the Flahertys’ strategies, quite independently of the fact that Moana was studio-financed and Nanook was not. Accounts of the film’s lengthy preparation in 1923 and 1924 depict a grotesque comedy of errors and misperceptions: anticipating a Polynesian counterpart of sorts to Nanook, the filmmakers were first confounded by the absence of struggle they found in Samoan life; expecting to find an Edenic island uncorrupted by the West, they encountered instead a corrupt New Zealand mandate lorded over by a Kurtz-like German chieftain who called himself “King of Savai’i” and entertained the natives regularly by singing opera. Dubbed the “Millionaire” by the Samoans after they saw his 16 tons of equipment, Flaherty screened Nanook for the islanders, but they preferred Galeen’s Der Golem. He spent weeks searching for dangerous sea beasts, even after being assured that none were around. The film’s first heroine disappeared after a tribal dispute, the second was disqualified after she cropped her hair; the orthochromatic film stock used in Nanook proved ineffectual in Samoa, and after Flaherty developed panchromatic stock in a local cave, silver nitrate deposits formed in the water, ruining all the initial footage and making Flaherty seriously ill when he drank the water. That a film as beautiful as Moana could emerge from these and many comparable mishaps testifies to Flaherty’s strength as a filmmaker, even if the film’s beauty derives almost as much from artifice as from actuality. When the camera pans extensively to follow the progress of Pe’a up a very high slanting coconut tree, we may be impressed by the Bazinian aesthetic of showing the event in its integrality; but when there is a cut to a closer shot of Pe’a pulling a coconut loose, one may well wonder if the latter was faked. The cutting of Moana’s siva dance similarly suggests a touch of possible contrivance, with the latter seen alternately against a dark and lit background. More crucially, it is worth noting that the elaborate tattooing shown was an obsolete ceremony when the film was shot, and the hero had to be paid a handsome sum in order to endure it willingly. If one also considers the rigorous stripping away by the Flahertys of all the 20th century intrusions on the island (apart from occasional acknowledgements of the camera itself) to create a non-existent paradise of uncontaminated innocence –- along with a sculptural sense of image that makes clear water appear as solid as marble, and a use of titles reinforcing the idealism (“The Sea -– as warm as the air and as generous as the soil”) –- one is reminded of some of the aesthetic principles of “imaginative documentary” subsequently developed by Leni Riefenstahl. Despite obvious ideological differences, the achievement of Moana — to depict a reality that is partially discovered and partially composed -– is similarly informed by a fascination with ceremony and ritual, a poetic use of archetypal figures as sculptural emblems (enhanced by the stunning photography and Flaherty’s first use of close-ups), and a utopian vision which seems to be largely made up of historical nostalgia. If the world of Moana remains partially false, the Flahertys none the less exhibit a fidelity to that falseness –- and a belief in its truth — that can be found only in the greatest of filmmakers.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

— Monthly Film Bulletin, December 1975 (vol. 42, no. 503)