The following piece appeared in the October 22, 2009 issue of the Chicago Reader. Due to a technical error which was belatedly corrected (in March 2010), the Reader omitted Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa’s name as coauthor, but I’ve restored it here. — J.R.

Kiarostami Returns

Jonathan Rosenbaum and Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa discuss the Iranian master’s first film to screen in Chicago since 2002.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum and Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa

Introduction

It’s been six years since Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and I published Abbas Kiarostami (University of Illinois Press), about Iran’s most famous and most controversial filmmaker. The book combined the perspectives of myself, an American film critic with a Jewish background, and Mehrnaz, an Iranian-American filmmaker and teacher with an Islamic background, on Kiarostami’s films, which are neither narrative features nor documentaries but something in between. Where Is the Friend’s House? (1986), Close-Up (1990), Life and Nothing More . . . (1992), Through the Olive Trees (1994), Taste of Cherry (1997), and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) keep altering the balance between what’s actually seen in a story and what’s implied or imagined, and this is part of what continues to make Kiarostami such a contested and fascinating figure. Building, perhaps, on his talent as a visual artist (he’s a photographer, painter, and graphic artist) and his interest as a chronicler of Iranian life, he’s been a nearly constant innovator in both form and subject matter.

For the book we wrote separate essays and recorded several dialogues about his career up through Ten (2002), his last film to have played commercially in Chicago. By then we’d also interviewed him together twice, about Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us, and later we exchanged faxes with him about ABC Africa (2001). More recently, we’ve recorded a commentary for the DVD of Close-Up that Criterion is preparing.

None of Kiarostami’s films have appeared on the art-house circuit since our book was published; they’ve screened exclusively in museums and galleries, mainly abroad. His feature-length Five (2004) and his half-hour segment in Tickets (2005), both available on DVD, haven’t shown in the U.S. at all. [Correction, 1/14/10: Five was shown at least once in New York a few years ago, and possibly twice.] Even the Gene Siskel Film Center, which hosts an annual Festival of Films From Iran, has so far shown only a making-of documentary about Ten and his half-hour Roads of Kiarostami. But his latest feature, Shirin, is showing at the Film Center this weekend, October 24 and 25, as part of the 20th annual Iranian festival.

Although I’ve seen Five on a big screen in Toronto, I think it works far better as a chamber piece to experience at home. I’m less certain about Shirin, which so far Mehrnaz and I have seen only in our respective homes. It premiered last year in Venice and has more commercial names attached to it than any other Kiarostami film—Juliette Binoche and 110 of Iran’s leading actresses. (By contrast, practically all the actors in all of Kiarostami’s previous films have been nonprofessionals.) But the stars are seen only as members of the audience at a film screening, and the film they’re supposed to be watching—based on a well-known Persian legend and medieval epic poem about a love triangle—is never seen, only heard. That’s because the film doesn’t actually exist: the actresses, along with the rest of the audience (men and women), were filmed in Kiarostami’s living room, where they followed his instructions. The whole thing, like so much of Kiarostami’s work, is an illusionist tour de force.

What follows is a conversation Mehrnaz and I had about Shirin, transcribed and edited for publication. — J.R.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM I’m fascinated by this film, Mehrnaz, but I also know that you see and hear more in it than I do because its raw material is more meaningful to you — not just the actresses but also the famous poem by Nezami Ganjavi (c. 1141-1209), Khosrow and Shirin, that the imaginary film is based on. Is this an adaptation that uses some of the poetry and adds some details and dialogue of its own?

MEHRNAZ SAEED-VAFA There’s no poetry in the film, only prose, and the dialogue is more formal than conversational. The film’s subtitle, “My Sweet Shirin,” is sort of redundant, because shirin already means “sweet” in Persian. But this may be a jokey way of suggesting how sentimental it is. And “My Sweet Shirin” also means “my sweetheart” or “my dear Shirin.”

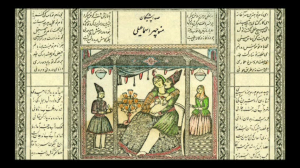

Nezami’s poem is built around a romantic triangle that offers two versions of the ideal man. (One is a king, who has power and status, and the other one is an artist.) The film begins like an authentic epic narrative film, with opening titles that are traditional illustrations of the poem. But then it shifts to the audience, close-ups of women, and that’s all you see after that.

JR Where Is Romeo?, which Kiarostami made in 2007, uses three and a half minutes of the same (or almost the same) footage, although the soundtrack is in English and seems to come from a real film.

MS Yes, I believe it’s Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968).

JR In 2004 Kiarostami did a three-screen video installation, Looking at Tazieh, at a couple of European locations, that showed a stage performance of a Shia passion play in the smaller center screen, in color, flanked by black-and-white videos showing the reactions to it by an audience at an outdoor theater. That audience is segregated by gender, but the audience in Shirin is unsegregated, and the only actor I immediately recognized, apart from Binoche, was Homayoun Ershadi, the lead actor in Taste of Cherry — although, like the other men, he isn’t featured. Strangely, the flickering light that falls on the viewers in the rear seats seems to come from a film, but the actresses shown in close-ups all seem to be lit by spotlights. Do you think Kiarostami used only nonprofessionals in the backgrounds?

MS I don’t know. Ershadi went on to play in other films, so he may qualify by now as a professional.

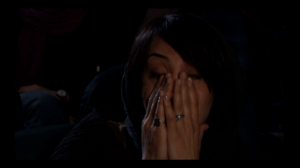

With the professional actresses, Kiarostami is obviously giving some kind of directions — when you see some of them flinching or chuckling from a sound cue, or crying, which comes later in the film.

JR Yes, he must be doing that — although he says he only picked Khosrow and Shirin as a subject after he shot all the footage, which is part of what makes this so skillful as an illusion of an actual film screening. The audience doesn’t seem real if you view it as a collective entity, because of the way everyone’s isolated. There are no couples or families or visible friends, and the emotional responses we see don’t spark one another. But the responses are very carefully calibrated in relation to what we’re hearing.

MS Yes, there’s always this isolation. You never see more than two or three people at a time — except for just one shot that shows us four.

There’s also something very interesting in the idea that comes from the disproportionate relationship between the rich soundtrack and the simple image — when the orchestra, dialogue, and sound effects (which include galloping and sword fights), the operatic sound of it — is juxtaposed with those close-ups. There are some things, like poetry in this case, that are regarded as sacred, so when you visualize it on-screen you reduce its significance. When you read Nezami or other classical Persian poets, you have an image in your head which is always greater than anything a film can show. The same is true with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet—as a text, I mean, which has certain symbols that a film of Romeo and Juliet wouldn’t and couldn’t have.

JR You seem to be saying that Kiarostami, by respecting the film in our heads, won’t interfere with it by offering an inferior substitute of his own. But in an interview on the Web site Offscreen he says, “Although you are free to imagine what you wish to, you have to see what I am showing. In fact, it is a combination of both freedom and restriction. I suggest you watch another world which is more attractive than the story. I believe if you dare let go of the story, you will come across a new thing which is Cinema itself. In fact, I suggest you let go of the story and just keep your eyes on the screen.” And this is the way I watched the film before I read this interview.

MS At times I got interested in just focusing on those faces, and at other times I forgot about them and concentrated on the soundtrack, such as the beautiful music by four contemporary Iranian composers — only one of whom, Hossein Dehlavi, is still alive. This is very different from Kiarostami’s other films, which mainly use only exit music, and it’s most often Western.

JR Yes, I noticed in particular those harp glissandos that seem to punctuate the unseen action. There are so many ways that Kiarostami seems to be making peace with and also employing a good many members of the Iranian commercial film industry. This has the longest and most conventional set of final credits attached to any film of his, even though it’s anything but a commercial product.

MS It’s funny, but this film seems to go out of its way to contradict what we think a Kiarostami film is. All the others are mixtures of documentary and fiction, but this one is only fiction. Unless you think of those close-ups as if they were screen tests. Because there are moments when those actresses don’t seem to be in total control over their own faces.

And some of the other typical things that people say about Kiarostami, that he favors long shots, for instance — the only long shots here are those implied by the music (the sound effects are all in close-up). You never see any.

I think this film is developing a theory about the audience that Kiarostami has been playing with and trying out in earlier projects. At first it was about leaving out some portions of the plot or certain characters so that the audience would imagine them. Now he seems to be asking not so much “What is cinema?” as “What kind of cinema is valuable?”

One could also talk about the issues of women in Iran. But the major thing he’s playing with is narrative and dramatic film and the idea of narrative cinema — which extends to the question of where film ends and film installation begins, and what you might have left when you take away the story.

JR You might say that he was already starting to address women’s issues in Ten. There’s a similar spread there in terms of age and class to what you find in Shirin. And during the film’s most tearful patch, we hear someone say, “Damn this men’s game that we call love.”

But when Kiarostami was asked why he opted for an “all-female cast,” he replied, “Because women are beautiful, complicated, and sensational,” and then added, “besides, women are more passionate. Being in love is part of their definition.” Which to me almost sounds like David O. Selznick.

MS If I was to take it seriously, it would be a very sexist definition. But I take it as a joke, a put-on. Sometimes he does that in interviews.

JR David Bordwell, who wrote about this film enthusiastically on his blog Observations on Film Art after seeing it in Hong Kong, began by saying, “Abbas Kiarostami has the widest octave range of any filmmaker I know.” And he went on to compare him to both Alfred Hitchcock and James Benning — referencing his respective flair for suspense and for landscapes, neither of which, incidentally, Shirin has even the slightest traces of.

MS In Five, Kiarostami shoots landcapes; here he shoots women’s faces as if they were landscapes.

JR Yes. And in both films there are virtually no real dramatic high points or low points. But I can’t say I was ever bored, either.

I also think Hitchcock is relevant for the way Kiarostami can trick spectators.

MS For me, the way he’s like Hitchcock is the way he looks at women who are reflecting horrors that we don’t see, with a lot of intensity. That’s also separate from whether or not they’re professional actresses.

JR Yet once again, he’s not making a film that’s likely to be seen widely in Iran — even though he’s perversely fulfilling the demand that many friends and critics, such as Godfrey Cheshire and Jamsheed Akrami, have been making to him for years, to make a film with a coherent story, well-known actors, etc. But people who might come to this one expecting to find the story of Shirin will feel cheated.

MS No, I don’t think this is a film for the general audience.

JR Yet he seems to be trying to engage with — or at least to be making a film about — the audience that he doesn’t have.

MS And the fact that we see all these women wearing scarves shows us that they’re in Iran. You can’t really disassociate this film from the present moment there, politically or otherwise. When you see these women crying, you can’t help but think of martyrdom. At the beginning, we even hear Shirin addressing other women, “Listen to me, my sisters,” about their common pain and her own story, and then at the end, she says to them, “I’m so tired, my sad sisters,” asking them whether they’re crying for her or for their own, inner Shirins. You can’t eliminate this context.