This appeared Cinema Scope no. 11 (summer 2002).Thanks to Francois Thomas in helping me clean up my German and French. — J.R.

“You can’t smell email,” Raúl Ruiz insisted to me the night before we had this interview at the 2002 Rotterdam Film Festival, explaining to me why he didn’t have any truck with the Internet. He added that lately he’s been collecting various first editions, excommunications, and death sentences, many of them from the 19th century and earlier, and he can smell all of them.

At first I was surprised by this old-fashioned form of resistance, but then the more I thought about it, the more I realized that Raúl is basically a 19th century figure. His largely Borgesian canon of 19th and early 20th century English and American writers (Chesterton, Stevenson, Wells, Harte, Hawthorne, Melville, et al) and his taste for rambling narratives and tales within tales smacks of a Victorian temperament.

I first encountered Ruiz’s work during my first trip to the Rotterdam Film Festival, in 1983, and it was there where we first became friends three years later —- as well as where we had this interview on January 26, in the lobby of the hotel where we were both staying. (Raúl had a small DV camera with him, and from time to time would idly shoot people coming through the hotel’s revolving-door entrance from where we sat a few yards away –- something, he explained, that he needed for his new Chilean TV series.)

Asked to produce a Welles tribute at the festival three months after Welles’s death, in early 1986, I met Oja Kodar —- Welles’s companion and major collaborator since the 60s — for the first time, and on my own initiative, knowing Ruiz’s affinity for both Isak Dinesen and Welles, lobbied unsuccessfully for Ruiz as the ideal person to film The Dreamers -— a cherished late Welles project starring Oja -— incorporating the material that Welles had already shot for it. (Oja, who held the rights, was willing to entertain the idea until she took a look at Raúl Raúl’s L’éveillé du Pont d’Alma [1985, see above] at the festival — not, alas one of Ruiz’s best. The project, however, might well have failed under any circumstances, given Welles’ reluctance to regard himself as anything other than a mainstream director in terms of his audience, some of which Oja has shared, even though his later features—-most notably, The Trial [1963), Chimes at Midnight [1965], and F For Fake [1975] —- showed exclusively in arthouses.) After that, Raúl and I crossed paths in San Sebastian and met on various occasions in other places, including Cambridge (when he was teaching at Harvard), New York, Chicago, and, most often, Paris, where he’s been living for many years on the rue de Belleville. (During this period I published a couple of extended pieces about him. The first, “Mapping the Territory of Raúl Ruiz” [1990], is included in my 1995 collection Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. The second — “Ruiz Hopping and Buried Treasures: Twelve Selected Global Sites,” which attempts to critique, correct, and supplement the first —- was published in the January-February 1997 Film Comment [and later in my collection Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons].) Over the past year or so, we’d been drifting out of touch, so this interview, suggested by Mark Peranson, offered a way of trying to get caught up again, or at least making a start.

As always seems to be the case with Ruiz, he has many projects in many different stages of realization or completion —- including a ghost story shot many years ago in Taiwan but still unedited, an adaptation of Gilbert Adair’s novel A Closed Book that was scheduled to start shooting in the spring, and an ambitious series for Chilean TV that he’s been working on for some time —- and, as usual, we only got around to discussing some of them.

***

1. Economic Changes

JR: How long have you been working on the Chilean project?

RR: Three years.

JR: Really. And it’s going to be how many hours long?

RR: I have just finished the fourth one.

JR: So it will be done like a serial?

RR: Yes, one hour and a half each.

JR: It will be weekly?

RR: I don’t know. That’s for the Minister of Education — or the Minister of Culture — to decide. It might show over a couple of weeks, or one week.

JR: The fact that you’re still doing things of this kind indicates that you’re still working in the same mode of production, but in other ways it seems like this must have changed over the last few years, since you’re also making more expensive films. Would you say you’ve changed the way you work very much?

RR: Things are very ambiguous in cinema. When you say more expensive films, yes, there is more money, but in film you have more possibilities with smaller structures. Let’s say, for something very normal, I am more anxious, fighting always with the production to hire more extras, fifty more actors there, and I have no control over it. For this project, I have the money, and this is about Chile, and that’s it. So I have the possibility to hire 100 Santa Clauses for a scene, or a big seven-metre-high box of matches…

JR: Like an Oldenberg sculpture.

RR: Yes. I put people inside, I put a whole school inside this box of matches, and a tavern, an evangelical church, etc. I could also use 200 people as extras if I want to — in a line, in the street.

JR: I realize that sometimes with lesser amounts that you can do more. But what I always remembered was very singular about the way you worked is that you seemed so relaxed. It seems when you have a lot of money involved, it would be harder to have a shoot in which nobody’s worried. I’m just curious as to how you found yourself, with some of the films you’re making, going through this change.

RR: I call that a kind of, well, capitulation. There was a moment where it was difficult and almost impossible to make the kind of film that I had been making.

JR: Was it basically that the sources of financing, like television, were not ready to make those kinds of films any more?

RR: Yes, all of a sudden there was nothing more with INA, which had been interested in all kind of experiments in cinema, and trying to work with filmmakers who were not only interested in the number of spectators or the traditional narrative ways of making movies. So at one moment, there was no possibility.

JR: Do you have a sense of why this economic change took place?

RR: In France, everything is connected with political power, and the Mitterrand government came into power. Because in the middle, in the left, there is the idea that cinema is the only real popular art, and democratic, like what they say about Jean Renoir and neorealism. I have nothing against that, but sometimes for me it is difficult, I don’t believe in this idea of a popular art, I don’t believe we can go very far in that way, but I believe in that moment we talked about in the 80s, 15 years ago, and the trouble started at the beginning of the 80s.

JR: So it was a supposedly left-wing government that did this.

RR: The right has had no real politics before Mitterrand. All the experimental work — let’s call it unusual work — that still exists in other arts, in music, other visual arts, is not recognized any more in cinema. It’s tough at the moment. Suddenly, they were confused by the open politics in the art. You know in France this was always true.

JR: What seems very paradoxical is that the moment when this began to happen is the moment of digital video, In other words, suddenly, when the means to make experimental work increased, the possibility of having it shown decreased.

RR: Yes. But still, this is France, and that means there is only the will of the State. The will of public authorities. That means literally that at the beginning of the 80s people making cinema were forced to move to video — I mean, forced. We got the money, we got everything, we got even more money than before, but we had to make it in video. And at that time, you know, the video was analog — we couldn’t use a small camera to make what could be reproduced in 35mm, or rework it digitally, and change everything. But at that time the will of the authorities was to develop in that direction. And that means aesthetic and economic tendencies are mixed with political tendencies, and not necessarily in a good or a bad way — sometimes it’s in a very good way. But it’s a funny thing about France that makes it different from the other countries, the political will — that sometimes the President can decide that in France we should make that kind of movie and not another.

JR: So what you’re saying is that potentially — this could be too strong a word — it becomes a kind of Stalinism.

RR: No, no, because you don’t go to jail. It’s kind of an 18th century thing. You feel like you’re at the time of Mozart, you have the money…

JR: Patronage, in other words?

RR: Yes. I am talking about the 80s. It’s still a game now. But in the 80s, people came to you and said, you have to make a film about this subject, you are free, you can do what you want, but this is the subject. Let’s say, to build a new building.

JR: Or the series about teenagers for French television, that’s an example from around that time. RR: Yes, there was a lot of freedom in that. But then they say, you must be finished September 17th because it is the anniversary of the President, and we have the invitations, and you can’t be late. It’s not very different from what happened in the 18th century in Europe. The President who decides to make a film for the birthday of his son or something like that. Or it was, of course, about the Republic. But it means more than that it’s connected with … how do you say, I have the German word, “Inhalt“, or “les contenu moral,” you know, the political aesthetic, it was not about that — the subject is this: spring in the city of Toulon, for example. Somehow it should be concerned with what happened in the spring in Toulon, and that’s it. I made a film [Les Divisions de la nature] about a castle, for instance, [Chambord] is just a castle, but it’s a kind of Disney inspiration, a very important moment in the history of France, and it’s a very strange form, funny, so you can play a lot with that. So I’m not complaining.

JR: Sure, but in terms of the change after that — was it making more expensive films in order to make less expensive film as well, or was it just that there were certain kinds of film that you wanted to make? The Proust film required money, obviously.

RR: Let’s say things happen to me. It’s not that I decided to do this and I tried for that, it’s what opportunities were there. Paulo Branco and I, we have more or less the same ideas in cinema, and he has the same ideas how to produce some people. To change from one filmmaker to another is a big choice, and not merely a technical problem, as it is now, for most producers. So his idea was that I was a good person to make very cheap, small, and free films. Only at a certain moment the unusual part was not very acceptable. So for a while I made more unusual and less expensive films but with no audience at all, not even my wife.

JR: Which films are you thinking about, for example?

RR: For example, there was L’autel de l’amitié (The Altar of Friendship, 1989), Le professeur Taranne (1987).

JR: And Tous les nuages sont des horloges (All Clouds Are Clocks, 1988), the one that you did with your students — is that also in this category?

RR: Yes, yes. And the Italian movies.

JR: Yes, none of which I’ve seen, unfortunately.

RR: You know that one of these movies, Viaggio Clandestino (The Secret Journey, 1994) was a movie that was supposed to be made just for one person to see, just him and some friends — literally, just like in the 17th or 18th century. But there were clandestine copies made, and suddenly RAI showed it ten times. So maybe it’s the film of mine that has been seen the most in Italy!

JR: That’s a little bit like what happened with Point de fuite (Vanishing Point, 1984), shot basically as a joke, which wound up getting bought by and shown on German television.

RR: Yes, yes, and was financed by City of Pirates (1983), which we made at the same time. The other film had a kind of patron, and this person paid for the film. But to come back to these big movies, at one moment Paolo said to me, “Maybe you could make these movies” — and a normal movie with very well-known actors was a new thing for him and for me both…

JR: Was Treasure Island (1985) a step in that direction?

RR: No, no, Treasure Island was a complete misunderstanding, because the money was there at the beginning and then suddenly the money was gone [not there anymore]. So I had to reduce the budget, and do it like a kind of B movie. This movie starts very strangely, with a good atmosphere, and then suddenly we are in a typical TV serial, because it was shot in continuity, so you can see the point at which the money starts to vanish…

***

2. Working Conditions

JR: I don’t know if you noticed this in the Rotterdam Festival catalogue, but it lists your films since 1984 and it includes Treasure Island twice.

RR: That’s because I made it twice, but one version is unfinished; I started it, but then there wasn’t any more money. Then there was something that was quite confusing: starting to produce films with la Maison de la Culture in Le Havre, trying to propose a model for making movies in the provinces outside Paris, like in the old B-movie studios in Hollywood, using the same sets and actors for the same movies. It didn’t work.

JR: Why didn’t it work?

RR: Because I didn’t find the artistic partners. Everyone wanted their own set, their own actors, their own crew. The idea that you had to use the same actors and cameraman that was used by another filmmaker was for many people like having to use the same toothbrush.

JR: There are still traces of that goal in what you accomplished — there’s the same space that’s being used in de Oliveira’s Mon cas (1987) and in your Mammame (1986), right?

RR: Yes, exactly. Sometimes it worked. De Oliveira was able to accept that kind of game, but not many others. The Centre de Cinema was reluctant to have this production outside of the system, and the professional producer complained about this, and there was public money that should be used for the distribution of culture and not production. Then there was the political game in the provinces. Finally it was half a failure, but we produced more than ten movies in a couple of years.

JR: And Mémoire des apparences (1986) came from that time…

RR: Mammame, Mémoire de apparences, La chouette aveugle (1987)…

JR: Three of your best films, in fact.

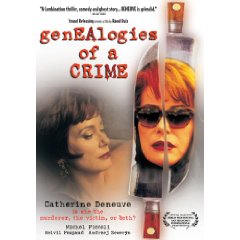

RR: They were free, for sure. I did not have a lot of money, but they were free. I started to really think about some theoretical topics that I developed later. And in that moment, Paolo talked with [Marcello] Mastrioanni, that it would be nice for him to go back to the period in the 1960s, when he used to make very unusual movies with Marco Ferreri. With Mastroianni and [his daughter] Chiara, I tried to make a narrative that was not conventional in that there was not one but three narratives that were combined in such a way that they could make a kind of cubist impression in narrative terms [Three Lives and Only One Death, 1996]. In visual terms it was very simple, it was kind of flat. And then there was Catherine Deneuve, to get back to the actors. The actors helped me a lot. I have to say that Deneuve accepted to make a movie with me, I only told her the story. She said you can use my name, I accept the movie, with no script at all.

JR: It seems to me that the Mastroianni film was very much in your earlier mode.

RR: Geneologies of a Crime (1997) was more ambitious than the others. And of course, the other one, which I was happy with, and I am still happy with, is Time Regained (1999). There were not so many worries with that one. This American accident, Shattered Image (1998), I fought to make, and I now have a film about what it means to make a film in America — why American movies are the way they are. It’s a very strange film because I thought about it in the terms of American movies. In the American cinema there are good guys and bad guys. The good guys are the artists, let’s say the filmmakers, and the bad guys are the actors, sometimes the producers. I found new bad guys, who were the technicians, the workers, who were so obviously disconnected with the project, with the story of the movie. In France, you can get a good price from an electrician if he likes a script, if he finds it interesting and not very commercial he can, let’s say, work Saturdays for free. And I thought that the relationship with the producer was ambiguous because he had the money coming from everywhere and he had to deal with those other producers, and everyone had a very precise idea about the movie. And the discussion was at the level of where to put the camera. That was new for me. The idea that I decided where to put the camera was new to them. The editor was the director, and not the cameraman.

JR: That’s extraordinary. So in other words that crew was accustomed to working on things with a director who didn’t decide where to put the camera.

RR: It seems to me most were coming from TV. Normally, the director does nothing, as the camera is placed by the cameraman, and the director looks when everything is ready, and then the actors are directed by the coach. There is no connection, and you are supposed to cover the scene. I was always arguing with the script girl, who said I didn’t cover the scene. And people would say where is the [covering shot, where is] the master shot? This was a film about dreams, and there were two dreams, so it was only mental images, and once you make an establishing shot you are disturbing the oneiric feeling. This is easy to understand. And they understood, of course, but they were still disturbed by the idea that there was no master shot or establishing shot. The idea that you had to convince people to do this and not that was new to me, and it was completely normal for an Anglo-Saxon mentality that you have to explain why you’re doing what you’re doing. In this last movie I made in Chile, I didn’t speak much, and they had no idea why I wanted something.

JR: But has it ever happened where you have to give different reasons to different people for the same shot?

RR: Yes, yes.

JR: In other words you can’t say the same thing to the cameraman, the producer, and the actor.

RR: In this case, the cameraman was Robby Müller, so he also had another approach. No, with the technician, it was for a simple reason. If you place the camera, say, vertically, it has to be a special task, so you have to wait for one hour. Normally I do it myself, and then ask the cinematographer to look and say okay. Robby accepted, because with many other directors in Europe it is normal to do that. But the technician was in a kind of shock that a director would do that and his cinematographer wouldn’t complain.

JR: One thing I want to get back to a little bit, because I’m curious about how it became different, in certain ways, was Time Regained. I would assume that one of the obvious differences in a production like that would be that more had to be scripted in advance, as opposed to your other films.

RR: No, many scenes were written on the day of shooting.

JR: They were? But of course you had the décor all ready and things like this.

RR: No, what would happen sometimes is that you have the description, you work with the art director or other people who work on the décor, and suddenly you end up with many more possibilities, so you have to use them.

JR: I’m also curious about what happened when you passed from Pascal Bonitzer to other screenwriters, if there was a conceptual change.

RR: Bonitzer and I are very old friends, so there was a kind of complicity. Sometimes I wrote the scene and he corrected the mistakes, sometimes he wrote them and I corrected. Many times he was in one room in my apartment, and I was in another one, and we worked on the same scene.

JR: I remember during that period you were thinking in terms of a lot of possible locations instead of sets…

RR: Yes, in Time Regained there were locations, there are some studio sets, but very few. Gilles Taurand was, let’s say, more professional, if you want to use that word. I gave the indication, and he wrote the script. And I wrote maybe only five scenes, not a lot. Normally I write half of the scripts, more or less.

JR: It’s obviously not the same, but I’m wondering if there’s any resemblance to what happened on Shattered Image, because you wrote less of that also.

RR: Shattered Image was written … yes, it was taken somewhere, it was kind of the results of some of the games I used to play in films. I wrote one scene in Shattered Image, the one with the witch. Because the scene was too conventionally mysterious, it was a kind of normal witch, with a young girl who helped her. I made it more of an everyday ceremony, not a special thing. So that’s not the only reason. In general I respect the script. As you know in America, there is a lot of rewriting, so you are never sure what you are shooting!

JR: This was the case on the Proust film?

RR: On the Proust film, during the shooting, I wrote all the story of the cup of tea, with Gilberte, because I was trying to find a way to show her avarice. Gilberte has a very complicated connection with money, she’s very stingy. She has real problems. And I wanted to show it without losing the romantic aspect of her. And suddenly with the cup of tea that was obvious. It seems to me it was a way to show that it was more than money, but her relationship with things, and the world that is disappearing. And I wrote that, and there was some rewriting by Gilles Taurand because I wanted to develop more a couple of scenes. And there were some scenes that were cut after that, because as you know the film was much longer.

JR: How long was the first cut?

RR: Oh, three hours and a half.

JR: I see. It seems like there were many cases where the premises were predicated on a certain advance planning … certain visual ideas that the scenes were built around. Things about changing perspectives a lot, particularly, in the opening sequence, but later also in Balbec also, which are very interesting because they make the scenes a little bit like theme parks. A shot becomes like a ride in some ways. I also remember that you had very strong feelings about the cast at one point; it seems like it must have gone through lots of changes.

RR: In Time Regained?

JR: I remember there was a time when there was a danger of Depardieu being imposed on you.

RR: Yes, yes, but the trouble was only with Charlus. The others, less … The fact is, you have to be very careful with Paolo Branco because he goes very fast. So you can say to him it would be good with that actor, and two hours later, he’s got him.

JR: There was an anticipation that to have someone who was not French doing Proust would be controversial, but it proved to be less controversial than expected. Did I hear correctly that you became a French citizen around that time?

RR: I am not a French citizen! No, no, no, I am Chilean. I am a resident. I tried to become a citizen many times, but there was always a paper that was missing. Then I decided not to try that any more, because you have fewer and fewer days in this life, so one day in itself becomes important.

***

3. Recent (and Not So Recent) Work

JR: There’s a recent film of yours that I haven’t seen, that was screened at Cannes last year…

RR: Yes, Savage Souls, Les âmes fortes, which is an adaptation of Jean Giono. That was kind of a compromise, but not really. Somebody proposed to me a script, I read it, and it was interesting for me to take a script that had nothing in it written by me. And it was a very unusual script, as it looks completely formal, normal, and flat, narrative and style on one level. But there were some surreal things, the way some of the events happened. It’s a very simple story with a young, beautiful, and poor girl who comes with her friend to a place, and finds a protector. You can see Emile Zola in the film, but it’s Giono, so it’s very ambiguous. The fact is this girl tried to destroy the protector for no reason at all because she is in love. And it’s this kind of love story between her and her protector. It’s not sexual at all. And the less sexuality you have there, the more it happens in real life. And she kills her husband, but you never know if she really does this herself or if she gets someone else to kill him, she’s very ambiguous.

JR: What’s interesting is that there’s a link here between your desire to hearken back to a certain traditional mode of production that involved taking on assignments, and not just generating all your own projects, which is what happened with Shattered Image and Savage Souls. But it seems you do an equal number of your own projects, though maybe not as many as before.

RR: The projects became big because it’s the only way at this moment, but I still have small things here and there and the digital is what makes that possible. The only problem is, I don’t know any cinematographers who can deal with the digital as it is now. It’s complicated. There is perspective, but it’s flat at the same time. So you’re in a kind of Flatland. I worked a little bit with Eric Gautier, who is great with classification of lights, and I worked with a Chilean cameraman, and I worked alone, and there’s that possibility that you can make your own image at the same time the film is being made, so you can play with this game. It was so extraordinary in L’Amour fou (1986) by Rivette, who used a combination of 35mm and 16mm. Now you can use a small camera and a normal one — a little bit bigger, with more stability — so you can move from one to the other.

JR: So that’s what you’re doing on that Chilean project?

RR: Yes, I’m playing with that. And the difference in palette between the two cameras is not enormous.

JR: I’ve noticed that the difference between analog and digital is becoming less precise, at least to the viewer. When you’re seeing digital, it’s not immediately obvious. But what about some of the deep focus, wide-angle effects? Are those still possible?

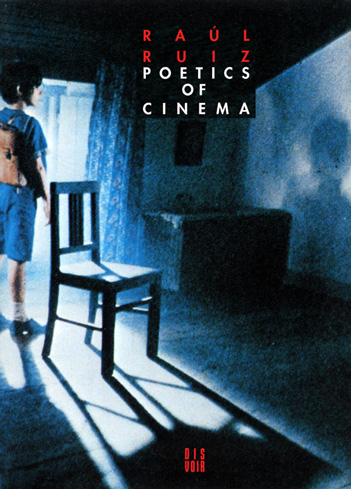

RR: I think now, yes. You have the simulation of 24 frames, which means you are close to real cinema. But what’s interesting as well is you can play with the film image or modify it if you want. Some of the ideas I had for making movies that I put in the Poetics of Cinema, for instance…

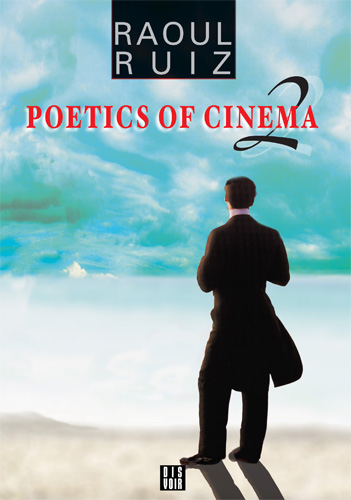

JR: Is there a second volume of this available in France now?

RR: There will be very soon. I reworked this general theory, which is more of a conceptual simulation, playing with the function of a shot. If you remember that the first statement that in a movie there is an image, or the audio-visual structure of images that push you to develop stories, and not the story that pushes you. That means you have to change the way of shooting. You have to deal with images first. Suddenly you realize there is some connection between objects, let’s say, and that gives you the idea to develop it a little bit more, and little by little you have a little microstory that if you succeed in connecting with the macrostory — let’s say the strategic story that the film is telling — you can make a connection between a normal narrative, if you want, and a not so normal one. But there are other possibilities.

JR: I haven’t yet seen your film with and about the artist Jean Miotte, but I have seen for the second time here Combat d’amour en songe ( 2000), and it’s a film that I feel very conflicted about. In a way it’s a lot like some of your earlier films; it made me think about your opposition to central conflict theory, as you discuss it in Poetics of Cinema. But in comparison to Manoel on the Isle of Wonders (1985), which is still my favourite in some way of your films, it loses me after a certain point. For the first 15 or 20 minutes, it seemed like this might be your richest film. But by the end, while it continues to be rich, it becomes harder to watch. And the reason why is that emotionally it seems to stay on one level, whereas in Manoel, there is more of a sense of a journey.

RR: Maybe, maybe. I’m not sure, what this film has is the structure — which is more explicit than in many others of my movies, because I practically describe the method at the beginning. So I have nine narrative topics, and they have a combinatory that is shown. And then the game I played was to write during the shooting, and when you do that there are high and low levels that you have, because of the freedom.

JR: One important determining factor, though, is that most of the film was shot in one location. Or was it two locations?

RR: There were a couple of places, yes.

JR: It seems to me there was one location in Portugal that was used in a lot of your other films. Was it a monastery you were using this time?

RR: No, no, it’s esoteric. You have many esoteric places in Portugal, and this is one of the most famous, in Sintra. And it was built using the number nine — and that was a hassle, because I didn’t know until I started shooting that suddenly everything was concerned with the number nine. So you can call that movie an esoteric movie, literally. We played with esoteric games and if you know those games you can give another dimension to the movie, but that means that when you play with all that combinatory, to me, that makes things colder.

JR: Yesterday, when we were both speaking at the “What (is) Cinema?” symposium here, I was arguing that in some ways, for some people, film is literature by another means. It seems to me that this film is literature by other means, in some ways, and I suspect that Miotte par Ruiz (2001), which I haven’t seen yet, is painting by another means.

RR: To me, in [the] Miotte I am just trying to discover what abstract painting means, at least for him. And what game he is playing. And little by little I discovered that he was playing many games — I made a list. And this game got more and more precise as the film goes on. Finally I discovered that he was making an explosion of painting, and then there was a kind of calligraphy with the black; sometimes it was good, sometimes it was less good. And the key to that movie is the character of sports; it’s sportive.

JR: This also makes me think that there is possibly a theoretical aspect, which I would connect with Mammame, which is the question of how you film painting, just as Mammame was about the question of how you film dance…I’m sure there are many other films we’re leaving out here. One played at the New York Film Festival and is about the little boy who is lost…

RR: Oh yes, La Comédie de l’innocence (2000). I have two films with the same name.

JR: Really? What’s the other one?

RR: La comédie d’innocence. I made it before. One is called Comédie d’innocence, and the other is called Comédie de l’innocence. Just for trouble, as you know, there is an enormous market of titles, and people protect an enormous number of them. You can put a title on a film and then discover that you don’t have the right because it is already protected by law, so that you have to pay royalties. So I used a title that was my own, and I then changed it a little bit.

JR: It seems to be there’s a danger that people eventually will order one film and wind up receiving the other! I also noticed that in the catalogue there is a film called Huub (1989). Is this the film you were making about the late Hubert Bals, the former director of the Rotterdam film festival?

RR: Yes, I made it, and I finished the first editing. Then after awhile the company went bankrupt, and then the material they had was sent to Duke University, where it is now.

JR: There are several of your films that are in this kind of limbo, aren’t there? The Taiwanese film … and, actually, I finally managed to get a copy of Manoel, but it’s the English-subtitled French dubbed version which was on Australian television. To me it was wonderful that it survived, because there was a time when no one seemed to know where it was.

RR: It’s in the Portuguese Cinémathèque.

JR: Oh it is. In the original Portuguese?

RR: Yes.

JR: That’s right, because the original three-part miniseries was never subtitled. I remember when it showed here in Rotterdam they had a voiceover translation.

RR: It was also shown in the Cannes festival, no?

JR: Maybe so — at least the shorter version, The Destiny of Manoel, was. I’ve never seen that — though everyone who’s seen both says it isn’t nearly as good as the original. But it was here, in Rotterdam, where I saw the full version. In fact, it was even given a prize here that year.

RR: I guess I wasn’t around at the time.

— Cinema Scope #11, summer 2002