This is second and (to date) final time that I did Cannes film festival coverage for The Village Voice, which ran in their June 29, 1972 issue. –J.R.

Surprises at Cannes: Huston redeemed, Tashlin reincarnated

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

CANNES, France — After 15 days of feeding in darkness, and blinking at the sun only between screenings, the Cannes Festival inevitably turns the persistent moviegoer into a blood relative of Dracula. regrettably, this year’s festival was long on celluloid — 700 films’ worth, according to Variety — but short on the lifeblood necessary to keep an honest vampire going.

Of the 34 films that I stayed to the end for, only one seemed to have the earmarks of an old-fashioned classic. Curiously enough, this came from neither Hitchcock nor Fellini nor Skolimowski nor Altman, but from john Huston — a director who has remained in limbo for so long that, until Fat City, it was hard to remember he still existed. Fat City may not be a great film, but it has the uncommon virtue of achieving practically everything it sets out to do.

Working in the U.S. for the first time since The Misfits, Huston returned to a milieu of failed boxers in Stockton, California, that he knew intimately as a young man, shot his story (from Leonard Gardner’s novel) in continuity, and wound up with what may prove to be his definitive statement.

One could go on at length about the finely tuned ensemble acting of Stacy Keach, Jeff Bridges, Candy Clark, Nick Colasanto, and Curtis Cokes (among others), and Conrad Hall’s beautiful lit color photography, which tells us things about crummy bars in the late afternoon and car interiors at night that we haven’t seen since the 40s — in black and white.

But the overriding triumph of Fat City is the nearly faultless direction, which uses these beauties not as distractions but as facets of a single vision. “I hope the boxers represent all the losers in life,” Huston remarked in his wonderfully hammy press conference, recapitulating a theme that has dogged his career since The Maltese Falcon.

But ultimately Fat City is less about losing than about growing old. In the final scene, as Tully and Ernie sit disconsolately at what looks like the world’s last lunch counter, and Huston suddenly cuts to a silent, static shot of the card players behind them, a sense of death and waste breathes across the film’s compassionate surface like an icy wind. As with Eugene O’Neill in Long Day’s Journey into Night — and, to a lesser extent, Robert Rossen in The Hustler — one feels that Huston has finally arrived at the one subject he can speak about without stammering.

***

Skolimowski’s King, Queen, Knave, which probably elicited more boos and jeers than anything else I saw at Cannes, was another pleasant surprise. For those who were expecting a respectable adaptation of Nabokov’s early novel, or an art-house classic to hang next to Le Départ and Deep End, the disappointment may have been warranted. The film is a reductio ad absurdum of Skolimowski’s favorite theme, manic adolescent horniness — carried to delirious and deadly extremes it has previously only suggested.

Stylistically, King, Queen, Knave frequently looks like an uncanny reincarnation of Frank Tashlin — a director who died in Hollywood less than a week before the film was screened.Not only are the loud colors, bitter comic book caricatures, and spirited vulgarity Tashlinesque; one also feels that Gina Lollobrigida takes over the Jayne Mansfield part in The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, while John Moulder Brown is made into an even more spastic Jerry Lewis.To defend this overkill is not to deny the charge of bad taste, but to argue that “bad taste” — much like “good taste,” and unlike absence of taste — can be a useful instrument of discovery: sometimes, given the subject, the only possible one. On a related plane, The Music Lovers may be precisely the sort of film Tschaikovsky deserves, and Such Good Friends a just rendering of what passes for urbanity and humanity in Manhattan.

Skolimowki’s theme has always had certain unstated affinities with teenage and pre-teen pornography (Little Annie Fanny, Wonder Woman, Esther Williams, et al.), but it is only in King, Queen, Knave that he carries this tendency to its logical-hysterical apotheosis: the Sex Goddess as Object, or, literally, a life-size Gina Lollobrigida doll. Since this sort of tackiness is largely a matter of ungainliness, it usually embarrasses anyone who identifies with it, and in order to approach this style profitably, one has to welcome the challenge of being embarrassed. For those unwilling to accept this challenge, the film may seem like a violation or a bloody nuisance. I liked it.

***

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Summer Soldiers, an odd and arresting fiction film about American army deserters in Japan, displays an open intelligence about its characters and issues that keeps them in a state of perpetual flux: every time we think we’ve pinned the situations down, the film does something to surprise us. Following a Southern deserter as a he roams uneasily across Japan, Teshigahara makes each of his encounters an unpredictable adventure and small comedy of manners. On the one hand, a lonely Memphis youth with scant knowledge of Japanese and a restless claustrophobia; on the other, a series of well-meaning Japanese citizens, equally bemused by the American, and usually at a loss to know what to with him.

Failed communication was already an important element is Teshigahara’s earlier Woman in the Dunes, but here it becomes the basis for a joint critique of American and Japanese insularity. (It would be interesting to see Summer Soldiers in a Japanese audience, to discover if the laughter occurs in different places.) The Southerner’s tragicomic odyssey is intercut with statements by another, Mexican-American, deserter, and the contrasts between the two broaden Teshigahara’s picture still further beyond the bounds of easy paraphrase. Such is the film’s openness that we respond both to the Japanese and American concepts of character reflected, respectively, in the direction (Teshigahara) and script (John Nathan — who I presume is American). The fact that this is Teshigahara’s first film not scripted by the novelist Kobo Abe may have something to do with its unusually free viewpoint. If it signals a new direction in Teshigahara’s work, one imagines that it will be an exciting path to follow.

***

For the second year in a row, the boldest new work I saw at Cannes was by Pedro Portabella. Umbracle, a multi-faceted statement of political despair from Franco Spain, is far more ambitious and open-ended than last year’s Vampyr, and even harder to encapsulate. The eerie, spectral imagery of Vampyr —- slightly over-exposed footage with bleeding whites and grays, where the light almost seems to come from another age, or planet —- persists in parts of the new film, when Christopher Lee takes hallucinatory trips across Barcelona, or visits a museum of stuffed birds in glass cages. Other sequences include a series of statements about Spanish film censorship, a Buñuelian tour of a shoe store, a traditional clown act filmed in toto, a lengthy clip from a Spanish patriotic-religious war film of 1948, a parade of chickens plucked clean in an automated slaughterhouse, and intercut snatches of Keaton, Chaplin, and colleagues played against a throbbing electronic composition with voices.

The use of asynchronous sound, already witty and suggestive in Vampyr, is here often turned into a blunt instrument of aggression: few directors since Hitchcock and Resnais have played so ruthlessly with unconscious narrative expectations to bug us. A silent image of a couple conversing in a living room is accompanied by loud knocks on a door that grow increasingly hard and abrasive, until we nearly scream that one of them answer the door.

This dislocation is an apt metaphor for the political frustration Umbracle deals with. (The title is Spanish for “wooden shutter”. After helping to produce Buñuel’s Viridiana and protesting the torture of political prisoners, Portabella has been denied a passport by the Franco government for the past four years.) Earlier in the film, a phone keeps ringing and no one answers; and in the penultimate scene, when a woman puts on a record of Beethoven’s Pastoral and moves towards a telephone, both record and image become “stuck” —- the same four notes endlessly repeat themselves while several shots show the fingers reaching, in separate angles, for the dial they will never reach.

Portabella travels a continuous treadmill that is contemporary Spain, that cannot be escaped, and can only be expressed by a scream. Umbracle, using a variety of means and tonalities, is a precise rendering of that scream.

***

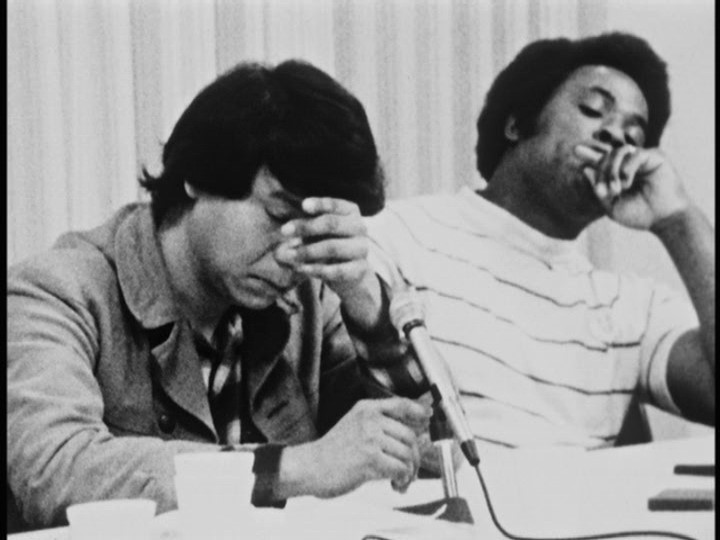

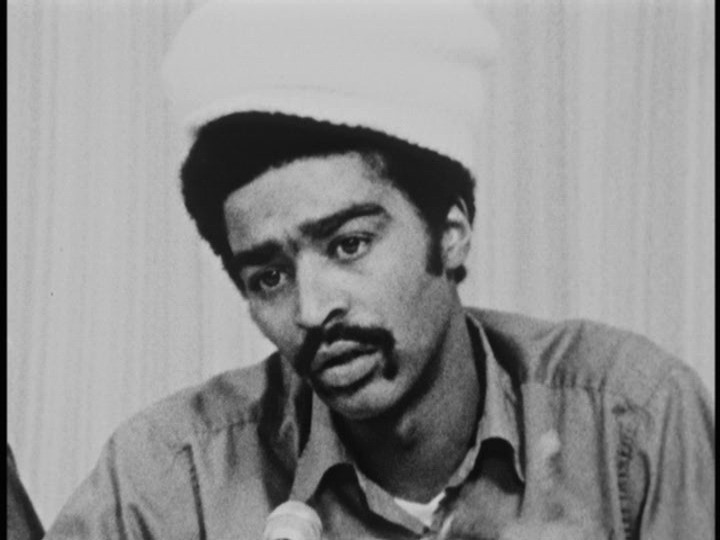

Winter Soldier — a straight recording of the confessions of war crimes given by American veterans in Detroit last winter — had an explosive impact on the international press. But the horror of what these ordinary, likeable veterans recount, and the courage they show by admitting to the blood on their hands is an experience every American owes himself, no matter how sick he is of hearing about the war. If these are the acts we are committing, we should at least take the responsibility of knowing about them.

As a significant example of how far we are from knowing, consider the reaction of Thomas Quinn Curtiss in the International Herald Tribune: “The witnesses disqualify themselves to some extent by their appearances…seeming on sight to be members of fanciful Bohemia. But if there is truth in their testimony, all reputable people will be deeply disturbed.” Reputable people are presumably those who wear ties, shave, go to film festivals, and are thus eminently qualified to comment on the crimes of Vietnam, unlike the badly-groomed slobs who committed, witnessed, suffered, and confessed them.

If there is truth of a representative kind in this reaction, then perhaps it is too late for this film — or film festivals — to have much meaning. But if any nerves or morals are left to be educated, Winter Soldier demands to be seen.

— The Village Voice, June 29, 1972