My first meeting with Samuel Fuller is chronicled in this interview/essay published in the July 9, 1980 issue of The Soho News and was reprinted in my recent collection Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues. Seven years later, while concluding my academic career at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I was placed in charge of running the film studies summer school program, I was still crazy about Fuller, and invited him to serve as our “visiting artist”, which led to our becoming friends from that summer until his death a decade later. I did my best to try to capture his singular way of talking in this article. For my title, I’m using the headline on that issue’s front page, not the title given inside (“Sam Fuller Reshoots the War”). — J.R.

When I enter his suite at the plaza, he’s finishing lunch, expressing his regret about missing Godard at Cannes, remarking on the absurdity of prizes at film festivals, asking me what Soho News and Soho are. (The one he knows about is in London — he fondly recalls a cigar store on Frith Street.)

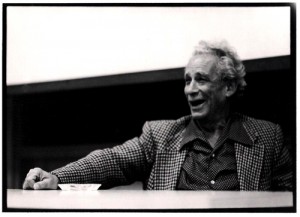

It isn’t hard to figure out why Mark Hamill affectionately calls him Yosemite Sam, or why Lee Marvin simply says he’s D.W. Griffith. Bursting with the same charismatic, comic-book energy that sky-rockets through most of his movies, old crime reporter, novelist, war hero, writer-director and sometime producer Samuel Fuller, almost 69, still moves and talks like his daffy action flicks — like the wild man from Borneo — in quick, short, blocky punches, like two-fisted slabs of socko headline type.

Practically everything he says and does conjures up a potential film sequence — even his descriptions of the ones he didn’t do. “I kept away from the blood in this completely,” he says a little later about The Big Red One, his long-awaited magnum opus about his extensive combat experience during World War II. “It was too easy. I gave it very serious thought. I’m having almost three years of combat in six countries — I mean, you’re wide open to make any normal picture look sick when it comes to violence. I could really knock ’em off their feet if I wanted to.

“I could have that whole beach the way it was in life, all filled with nothing but intestines,” he says dreamily, visualizing that possibility in his mind’s eye. “That’s over 900 yards of just guts. Don’t know who they belong to! Bodies, too — a head here, an arm there, an asshole here, it’s all over the place. But I’m driving everyone out of the theater!” As though to compensate for this uncharacteristic restraint, The Big Red One contains more verbal violence — ordinary soldiers’ profanity — than all of Fuller’s ’50s war films combined (The Steel Helmet, Fixed Bayonets, Hell and High Water, China Gate, and Verboten!), none of it excessive.

“And I was not interested so much in the violence on the screen,” he continues, “as in the violent emotional reaction of an audience.” I’m reminded of one of the few gory details in the film — handled humanely, almost the way Howard Hawks would have done it, as a literal throwaway gag — when a dogface named Smitty, who’s just been ribbed about his low survival potential as a replacement, is sent out for water, steps on a mine, and loses one of his balls. Just like that. (Lee Marvin, the sergeant, is the one who throws it away, reminding him that he can get by with less than two.)

“I don’t like my young men even to try to emote,” Fuller is saying. “I want the audience to emote. Moving relentlessly to another area, another, another. And the reactions are very personal — generally it’s greedy, miserly, highly parsimonious as far as life is concerned: `I’m gonna live.‘ They don’t say it, but `I’m gettin’ my ass outa here!”

Logically, then, The Big Red One is the story of survivors, Fuller included. He sees it that way himself: “These are the guys who made it. Even if they had to use other guys to live, they made it. I kept away from what I think was all the old corn, like a man getting shot when he’s reading a letter from his sweetheart — and don’t forget, I’m guilty of that too, in other pictures. I decided I’ll do something that I don’t think I’ve seen in any motion picture, in any country — where you follow several men, in this case five, and they all live. Have you seen one?”

***

Manny Farber, who more or less discovered Fuller back in the early ’50s, has written eloquently about both his “comic-book lack of self-consciousness” and his conceptual brilliance (“Blunt and abstract, he often measures a scene into stylized positions and chunks of time”). Together these factors contrive to challenge some of our received ideas of what artists and poets are supposed to be like, particularly in rural Manhattan. Fuller’s reputation is that of a primitive, and a friend has rightly called The Big Red One an antique, a ’50s war film. Yet to my mind, it’s also the most intelligent American movie in any genre I’ve seen this year.

“With Fuller, one always finds both a war correspondent and a mad educator,” writes Serge Daney in a recent Cahiers du Cinéma. “He takes off from an implicit idea: the spectator knows nothing — or practically nothing.” Thought out and reflected upon over 30-odd years, shot mainly in Israel, mucked around with by Lorimer (who hated and discarded his own two-hour cut), and now in the process of opening, Fuller says, “all over the world,” The Big Red One is a distillation that remains simple and crude on some levels, densely felt and thought on several others. The fact that it deliberately includes no overviews of war, no basic training or flashbacks to home life, is one of its strongest points conceptually.

On the one hand, it’s as didactic as a film by Godard or Rossellini (Les Carabiniers and Germany Year Zero both spring to mind), telling us that War is X and Y and Z — every scene has a specific point to make. On the other hand, it’s lunatic poetry that has a lot more to do with feelings than with facts. “When you can’t tell the crazy from the sane, that’s pretty hard for a soldier,” admits Zab (Robert Carradine), the film’s narrator and Fuller’s autobiographical dogface stand-in, in a line ironically not written by Fuller, “but it’s good material for a novelist.” [2009 footnote: This line was written by filmmaker Jim McBride.]

This comes right after some skirmishes in a madhouse, filled with apparently feckless refugees from Fuller’s Shock Corridor (and Stéphane Audran as a Resistance spy). One of them picks up a stray machine gun during a battle in the mess hall and starts to shoot people gleefully at random, boasting, “I am one of you! I am sane!” “To make a real war movie,” Fuller boasts in the movie’s pressbook, “would be to fire at the audience from behind a screen” — hastily adding that, “Anyone seeing The Big Red One will survive.”

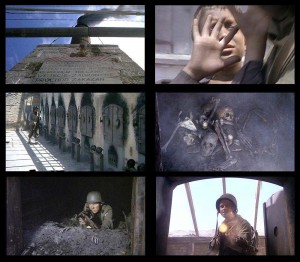

Consider his standard method of directing a shot, which sounds like a dime-store definition of existentialism: firing a gun loaded with blanks to start a take, then saying “Forget it” to the actors and crew in order to end it. Consider, too, the surrealist images that keep cropping up in The Big Red One: ants crawling out of a large, wooden crucified Christ on a battlefield; a procession of U.S. soldiers through a field of rubble, led by a Sicilian war orphan with a brightly colored cart carrying his dead mother; repeated glimpses of a wristwatch on a corpse at Omaha Beach in Normandy on D-Day, covered each time by increasingly blood-soaked waves (like the stream in Jancsó’s Red Psalm).

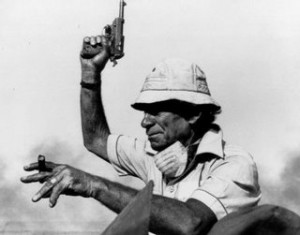

One of Fuller’s original concepts that seems obscured somewhat in Lorimar’s release version is the use of the benign father sergeant figure (Lee Marvin) as a symbol of death. “In my mind, he is death and so’s the German officer,” Fuller says when I bring this up. “It’s the idea of death versus death, ’cause that’s war. It’s not man versus man. Who the hell does win if it’s death fighting death? You don’t win and you don’t lose. Either way you die, so it’s all horseshit.”

There’s a very strange, virtually silent sequence between a Marvin and a mysterious anonymous little boy whom he finds in a liberated concentration camp in Czechoslovakia near the end of the war. Eerie and totally unconvincing on a naturalistic level, it reminds me more of the Princess Wakasa episode in Ugetsu Monogatari than anything else — a love scene with a ghost.

It occurs shortly after Griff (Mark Hamill), who has heretofore been portrayed as a coward afraid to shoot, finds human bones inside a crematorium, then a live German solider inside the next one — and proceeds to fire at the latter again and again, coldly and maniacally, at a funeral-march tempo. The refusal of Fuller to cut away from Griff to a second shot of his target is very disquieting: “That’s for you to feel what’s happening to that body on the skeleton. I don’t want the audience to see it — I want them to feel it.”

It seems significant that Fuller is currently being courted by Serge Silberman, the producer of Buñuel’s recent surrealist films. “Yaah!” he hollers, rebel-style, when I mention Buñuel’s name. “That’s why I had a hard-on for him, boy, he puts all the loot up for Buñuel, and I love that man. I’m seeing him in July. He came to see me in Cannes, he came to see me in Paris. It’s a project called The Tunnel; it’s been a best seller in France the past six months. It’s a big picture, a big book — it’s very thick.”

And in Fuller’s own novel of The Big Red One, just published by Bantam, along with some characteristic Fuller oddities — like naming all his French officers after French film critics (Moullet, Lourcelles, Chapier, Tavernier) who’ve championed his films — there’s a brief quote, in introducing the section set in Belgium, that’s as vivid as a line from Lautréamont: “`Why are you crying?’ — an insane child to a burning tank.”

Park Row — being shown at the Public Theater at 10 p.m. on July 16, with Fuller in attendance — is a cornerstone in George Morris’s welcome and ongoing Fuller festival, which ends on the 20th. It’s Fuller’s favorite among his own pictures, and mine too — financed out of his own pocket on a shoestring, and chronicling several events in early tabloid journalism in New York.

There’s an agreeable, demented effort to work the title into practically every major speech, which seem to take place every ten minutes or so. It’s the film that comes closest to summing up Fuller’s experiences as a reporter. When I mention that The Big Red One often reminds me of it — because both are about the interaction of a group of people — he says, “You’re right exactly, it’s a squad.” And, referring to the newspaper editor, Phineas Mitchell (Gene Evans), “He’s the sergeant with the squad.”

Describing his own cold-bloodedness as an editor, on his two-hour cut of The Big Red One that Lorimar rejected, Yosemite Sam says, “My little girl Samantha had a scene that’ll knock you off your ass, a scene in a barn with Mark Hamill and the other guys — a wonderful scene, fresh. Out! Stopped my tempo. I tried to explain it to her.

“My wife Christa had one of the best scenes in the picture — everybody admitted that — with the German. A very important scene to explain why people went for Hitler. Simple, very simple. Money. M-O-N-E-Y. `I don’t wanna lose my house or my bank account, house or bank account.’ The whole world is the same all over. All over! Forget about countries: money, bank account, money, house, home, earth, bank account.

“That’s the crux of civilization. Always remember that. Always remember — it’s the reason for killing, it’s the reason for fucking, it’s the reason for living: loot. I don’t care if it’s the church using it — ugh, that’s horrible, using that and death, it’s terrible, big fiasco. But the bottom line — it’s like Billy Graham, can you imagine him saying, `I wanta speak to all you people and I only want a dollar a year’?”

He laughs raucously. “So this other cutter did a very good job, except, for my money — this is no secret — I like 90 percent. The 10 percent was all right for any cutter, but not to the writer. Forget the writer. The quick little thing, chopped off — he would never know about it, how would he? There’s no blame. But that’s why I wrote it, for that quick little thing.”

Fuller’s first cut was four hours and twenty minutes long. “Second cut, two hours. Second cut they hated. They wanted the elements of the four hours and twenty minutes. Sizewise, impossible. In my cut, I took out sequences — I don’t circumcise or shorten scenes. That’s when they hit the ceiling, see. The general thing is to boil down the scene — like a man on a horse galloping up to the ranch house. If you cut the goddam cop getting into the car and driving through New York City, that’s easy to cut, ’cause that’s padding.

“I don’t write padded scenes. I never did. Good or bad, whether you like my copy or not — unimportant. I always hit the hard thing right away. It’s very tough to get that. The easiest thing is to build. When you’re padding, you’re chicken. Always remember that.”

So it isn’t coming out exactly the way he wanted it to — but it is coming out. Sam the Man is back in business, and if you want to know why expensive masterpieces can’t get made anymore, check out Pauline Kael’s industry piece (“Why Are the Movies So Bad? or, The Numbers”) in the June 23 issue of The New Yorker. Meanwhile, check out The Big Red One for more eccentric, juicy personality per square inch than can be found in all the diverse disco parlors of The Empire Strikes Back, Urban Cowboy, and Crazy Eddie. More intelligence, too.

— The Soho News, July 9-15, 1980