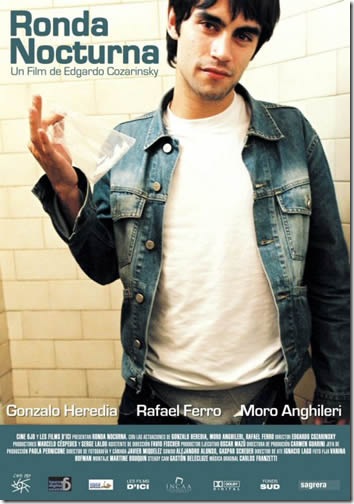

From the September-October 1995 issue of Film Comment. I should stress that this essay is very much out of date once one starts to consider Cozarinsky’s prolific subsequent career as both a writer and a filmmaker — although I’ve anachronistically included a few more recent book covers and film posters as illustrations, as well as a poster and two stills from his most commercially successful film to date, the 2005 Ronda Nocturna, known in English as Night Watch, in part to help make up for the impossibility of finding stills for some of the rarer films of his discussed here.

Let me also quote my Reader capsule review of Night Watch: “With a few exceptions, I prefer the literature of Edgardo Cozarinsky, an Argentinean based mainly in Paris, to his films, and his nonfiction in both realms to his fiction. But this poetic, atmospheric drama, shot in Buenos Aires, challenged my bias, mixing the natural and the supernatural, the cinematic and the literary, with such assurance that Cozarinsky no longer seems like a divided artist. Following a teenage street hustler through the night of All Saints’ Day, he turns a documentary about his hometown and its street life into a haunting piece of magical realism. (The original title, Ronda Nocturna, translates more accurately as Nocturnal Rounds.) In Spanish with subtitles. 82 min.” I should add that Cozarinsky — a friend since he moved to Paris in the early 1970s — spends much more of his time nowadays in Buenos Aires. One of his more recent films, which I saw at the Viennale, both fascinating and haunting, is Notes for an Imaginary Biography [see first photo below], an hour-long montage composed of outtakes from many of his previous films.

I’m happy to add that a Spanish translation of this essay has been added to the Argentinian edition of my collection Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, which came out last year. — J.R.

Ambiguous Evidence: Cozarinsky’s “Cinema Indirect”

Critic and artist, filmmaker and writer, storyteller and essayist, Edgardo Cozarinsky is a Paris-based Argentinean probably best known in this country for his film La guerre d’un seul homme (One Man’s War, 1981) and his books Borges in/and/on Film (1988) and Urban Voodoo (1990). A cursory account of these works would describe the first as a documentary, the second as criticism (by Borges as well as Cozarinsky), and the third as fiction; but a closer look, particularly at the first and third, suggests that things are rarely quite that simple in Cozarinsky’s oeuvre. Working with documentary materials — French Occupation newsreels and passages from the diaries of Ernst Jünger, a German officer posted in Paris over the same period — One Man’s War places itself somewhere between essay and fiction, whereas Urban Voodoo, described by Susan Sontag in her introduction as “an album of postcards made of words only,” consists of semiautobiographical narratives interspersed with quotations from other writers, and might be said to breathe in a similarly ambiguous netherworld.

Born in Buenos Aires on January 13, 1939, Cozarinsky made his first film there, the not-easily-categorizable … (Dot Dot Dot, 1971), before moving to Paris more or less permanently three years later. Since then, broadly speaking, his fiction features — Les Apprentis sorciers (The Sorceror’s Apprentices, 1977, see photo above), Haute mer (High Seas, 1984), and Guerriers et Captives (Warriors and Captives, 1989) — have rubbed shoulders with a dozen documentaries or essays on film or video. His most recent is Citizen Langlois (1995), about the French Cinémathèque’s Henri Langlois.

The following article, written for a [then-] comprehensive retrospective of Cozarinsky’s work curated by Danièle Hibon for Paris’s Jeu de Paumes in spring 1993, can’t claim to be exhaustive; it was written after seeing only seven of Cozarinsky’s films, some of them many years apart. (I later saw The Sorceror’s Apprentices at the retrospective itself.) At best it should be regarded as an interim report on the work of a filmmaker whose methods should be read as a series of strategies for dealing with both marginality and exile — in relation to genres and forms as well as languages and countries.

1

…Where all possibilities are plausible, perhaps none is true?

Around me, private history and public history cross each other without meeting….

— Edgardo Cozarinsky, Boulevards du crépescule

Apart from a brief summary of Ernst Jünger’s life and career up to 1940 (when he was posted as an army officer in Paris), the first section heading, “1. Andante con moto,” and the opening credits, the first two verbal texts we encounter in One Man’s War — the two bread slices sandwiching the three elements cited above — concern the “documentary” texts that comprise the film’s two principal ingredients: weekly newsreels and personal notebooks, both dating from the early Forties. The brief printed text about newsreels, written by Cozarinsky, tells us that in a period before television, when cinema attendance was massive, weekly newsreels were the only opportunity for a very large public to see moving images of current events. And the opening spoken text by Ernst Jünger about his personal notebooks and diaries, read offscreen by Niels Arestrup, tells us that he keeps them locked in a steel safe in his hotel room -– a safe provided to him to house confidential files about disputes between French army and Nazi officials. Objects such as these safes, he notes dryly, are only symbols of personal status, and if this status should ever be questioned, such precautions would become meaningless.

In the dialectical play between these two texts about texts — a dialectical play involving public versus private (and hence advertised versus secret), the masses versus the individual, onscreen versus offscreen, printed versus spoken, supposed “objectivity” versus supposed “subjectivity,” and open spectacle versus fear of discovery — the “cinema indirect” of Edgardo Cozarinsky has already begun to take shape. Whether taking the form of popular, everyday spectacle or of private reverie, the two basic texts of One Man’s War are mechanisms for normalizing and justifying the intolerable, and the means by which Cozarinsky chooses to expose these mechanisms are those of indirection. “I am only interested in `cinema indirect,’ if it exists,” he remarked parenthetically to Thomas Elsaesser (the emphasis is mine) in an interview about One Man’s War — an interview significantly carried out in both Berlin and Paris.

Why “cinema indirect” and not “cinema direct”? Because, from one point of view, the films, stories, and essays of Cozarinsky all tend to drift around the delicate and paradoxical issue of how to deal with fiction and fantasy without lying, and “cinema direct,” a form of film rhetoric and style that for many viewers automatically becomes a signifier of truth and the “real,” falls too easily into the practice of lying. (Jean Rouch undoubtedly had this point in mind when he employed “cinema direct,” a technique central to his ethnographic films — many of which unabashedly incorporate elements of fiction –- in his only pure fiction film, Le Gare du Nord [see photo below], his contribution to the 1964 sketch film Paris vu par…) And as the Mythologies of Roland Barthes (among related enterprises) remind us, “news” and “documentary” can all too easily cloak their myths — their ideologies and other unstated suppositions –- behind related signifiers of actuality.

From this point of view, the newsreel footage and the diary entries that rub shoulders in One Man’s War are two forms of self-justifying fiction, and the motivation for juxtaposing them is the desire to bear witness to the “real” sources and provocations they have in common. Like the multiplication of two minus signs yielding a plus, this multiplication of two fictions yields a common concealed space that each fiction strives to rationalize and domesticate. Cinema indirect becomes the means for bringing this concealed space to light.

Like the deliberately artificial and unstable spaces created between Paris and Buenos Aires in much of Cozarinsky’s work, between fiction and nonfiction, between literature and cinema, between “postcards” and quotations, between native tongue and exile tongue, and ultimately between politics and art, this cinema indirect is quite literally founded on a theoretical impossible space –- a realm of intervals, of in- betweenness, paradoxically defined by its own conscious marginality and lack of definition. Its only certainty, one might say, is a complete absence of certainty.

As Richard Porton has noted of One Man’s War:

A currently fashionable tenet advocates the view that history can only be evaluated within a textual framework, but this film moves beyond that by-now moldy truism to demonstrate the instability and outright mendaciousness of textual evidence. The newsreel sources are fascinating relics of societal bad faith, and this gargantuan exercise in self-deception is mirrored in the diary entries of Jünger that provide the film’s ectoplasmic voice-over narration. (As Thomas Elsaesser remarks, the film is interesting precisely because we know less after watching it than we did before.)

One reason why we know less is that even the satisfaction of being told a linear narrative is disrupted. Although the film begins with Jünger’s early days in France and ends with the Liberation of Paris, the achronological arrangement of many of the diary entries that figures in between confounds any possible sense of progression or development in his thought. (In some segments, the entries even proceed backwards: in one portion devoted to 1941, we move from December to October to June to January.) And the nature of Cozarinsky’s mosaic structure of both text and newsreel material, not to mention his juxtaposition of the two -– counteracted in turn by his disjunctive uses of “Aryan” (Hans Pfitzner, Richard Strauss) and “degenerate” (Arnold Schönberg, Franz Schreker) musical accompaniment, and his division of the film into four chapters marked by musical indications –- compels us to regard the film-as-a-whole as an abstract composition at least as much as a collection of documents. Thanks to these strategies, as the film advances, our awareness of what it leaves out and refuses to say becomes every bit as important as what it includes; it is in all the unstable spaces between Cozarinsky’s elements (newsreels, diary entries, music, punctuations of black leader) that his darkest and “truest” meanings take shape.

2

Over the most pedestrian images of Buenos Aires…the commentary speaks of Calcutta and a 30s dance band plays a Russian song. The commentary is delivered in the fake Spanish of Fitzpatrick travelogues distributed in Latin America; behind that, one can make out a fake English, a “made in Hollywood” Hindu.

— from a sequence-by-sequence description of … (my translation from the French)

It surely isn’t by chance that Cozarinsky’s first film, made in Argentina, is named after an ellipsis. “Le regard de l’outsider” (“The Gaze of the Outsider”), the title given to his brief critical study in Cahiers du cinéma of the role of ellipsis in Lubitsch — an article that begins suggestively by citing the careful “reading” of dirty dinner dishes by Lady Barker’s servants in Angel in order to intuit the precise mental states of the diners they are serving -– is an expression reflecting the particular and central roles of ellipsis and synecdoche found in his own work. Not having seen … for roughly two decades, I would be incautious in attempting any detailed analysis of this independent, “underground” feature, but one general observation about its structure seems worth making. Like Godard’s 1+1, Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism [see photo below], and Mark Rappaport’s Casual Relations — among many other characteristic works of roughly the same period — Its overall method is to juxtapose disparate texts and discourses rather than attempt to synthesize them. These texts and discourses, one might add, are ones in which fiction and nonfiction are accorded an equivalent and perhaps even interchangeable status — an attitude that is to recur often in Cozarinsky’s subsequent work, in film as well as in prose. (Admittedly, most of the film’s 17 sequences are devoted to an episodic narrative involving the same nameless male protagonist; but if memory serves, the overall effect of the film’s breakdown into discrete sequences is still largely one of gaps and discontinuity.)

This method of dealing with cultural and textual overload — a specific legacy of the political, philosophical, sexual, and artistic upheavals of the Sixties, perhaps best exemplified in the Sixties films of Godard – invariably evokes some notion of synthesis and praxis while simultaneously acknowledging the absence of any single unifying system that might bring about such a fulfillment. This articulated impasse is reflected in the very titles of these films, which refer to simple addition, “mysteries,” “casual relations”…and, finally, intervals, the spaces in between. (Significantly, the use of black leader as a form of cinematic punctuation — an important element in One Man’s War — was first becoming widespread during this period.)

Eighteen and 21 years later, after two decades of political exile, Cozarinsky’s two Argentinean “homecoming” films, Warriors and Captives (1989) and Sunset Boulevards (1992) — are both concerned with the emigration of French citizens to Argentina, thus comprising a precise reversal and mirror-image of Cozarinsky’s own emigration and exile. This is explicitly acknowledged in Boulevards — not only in shots moving from the Eiffel Tower to a sign indicating “Rue Buenos Ayres” and, conversely, from the Argentine métro stop to the Arc de Triomphe, but also in Cozarinsky’s own offscreen narration:

I went looking for traces of Falconetti and Le Vigan. What were they looking for so far away? Perhaps, very simply, they were chasing the most obstinate of mirages, trying to start over at zero. The same thing that pushed me to make the opposite voyage. As a young man, I dreamt of living in Paris. Today in Paris, I think of the city of my adolescence…the cinemas which have now disappeared, where I learned to recognize another world full of promises….Today the only films which make me dream are those I want to make….

On the other hand, as the deconstruction of a “Buenos Aires” travelogue in …, described above, suggests, Argentina was already “somewhere else” for Cozarinsky, even before he became a literal exile — a cultural melting pot, as it already was for Borges, of European and North American as well as more indigenous South American elements. Like much of Cuba during the Sixties, it can be read as a cultural crossroads whose whose overlapping influences, like a set of transnational filters, yields a sustained cosmopolitan irony with certain ties to a camp sensibility.

The first of these “homecoming” films, a bilingual Western (though perhaps it should also be called, given its geographical setting, a Southern) and French-Swiss-Argentinean coproduction, set near the Patagonian border around 1880, is perhaps the Cozarinsky fiction film that could most plausibly be called “classical”. Yet it is a “classicism” that, properly speaking, still exists between quotation marks -– which is not surprising insofar as its scenario and dialogue are credited “in homage to Borges” (one of Cozarinsky’s two most famous teachers, the other being Barthes.*) The film shares with Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West both an outsider’s look at the Western genre and a preoccupation with the “coming of civilization” to the wilderness that is quite distinct from the garden-wilderness dichotomy found in the Westerns of Ford. For “civilization” in this case largely refers to both Europe and the U.S., not only to Buenos Aires, and the transactions between these forces and influences are fundamentally what the film is about. Thus Marguerite (Dominique Sanda), the new French wife of Colonel Garay, wants to escape her European past, while her husband wants to turn Argentina into the most modern country in the world — “modern” in this case meaning “as powerful as the U.S. and as civilized as Europe”. And Madame Yvonne (Leslie Caron), who establishes the first capitalistic brothel on the front, gives her half-breed prostitutes French names in order to attract customers with her own brand of ‘civilization”.

But these transactions are mainly dealt with thematically rather than formally, apart from the bilingual dialogue and the generic references. As in Cozarinsky’s two other fiction features, The Sorcerer’s Apprentices and High Seas, the task of telling a story with actors and mise en scène, which entails the viewer’s suspensuion of disbelief on some level, necessarily obliges one to suspend part of the radical questioning of documentary authenticity that lies at the heart of his more essayistic features. (It might be added that Cozarinsky is on the whole more comfortable in dealing with texts than with actors, as some of the awkward performances in both films suggest. One reason, perhaps, why Warriors and Captives suffers less in this respect is that Sanda and Caron are both partially used as texts — that is, bearing the freight of their previous screen appearances.) Clearly Cozarinsky is himself aware of this problem, as his recourse to certain documentary materials and methods in both of these European features suggests.

In High Seas, indeed, it appears to be actuality itself that produces the need for fantasy. I’m thinking not only of the newsreel images of paratroopers that appear at the beginning of the film and recur later, but even more of the literal assault of the news on the protagonist, a Swiss insurance salesman named Eric Lint (Andrzej Seweryn) vacationing with his wife in Rotterdam: the radio bulletins and the newspaper headlines about the CIA, the KGB, “France to Arm Chad Against Libya Threat,” and so on, all of which distract him from his wife’s chatter and seem to create a whirlpool of torment that a mysterious redheaded woman (Willeke van Ammelrooy), a captain on a three-masted schooner, turns up to rescue him from — a figure out of Isak Dinesen (perhaps by way of Tay Garnett and Albert Lewin) who promptly whisks him away into adventure. Like the blue-sheeted bed on the schooner where he makes love with La Capitaine, which promptly turns white as soon as he gets up, the surfaces of this film are in a way as mutable as thought itself — and just as apt to evaporate on a moment’s notice. A comparable relationship can be felt between the paranoid terrorist plot of The Sorcerer’s Apprentices, the interpolated scenes from Danton’s Death (played by Niels Arestrup, jean-Pierre Kalfon, and Pierre Clementi), and the more documentarylike rendering of Paris in fall 1976 underlying the main narrative –- as if three separate blocks of material were all competing for supremacy, each in turn overtaking the other two.

At the heart of the matter, it would seem, is a deep-seated conviction that actuality and fantasy are both matters of selecting and editing endless reams of material — the practice, in short, of a writer and a filmmaker. In this respect, it is worth citing the last two sentences in a brief autobiographical text written by Cozarinsky for inclusion in a Ph.D. thesis on One Man’s War by Henry McKean Taylor — a statement that acknowledges the degree to which Cozarinsky’s sense of his own identity is a matter of editing choices:

…I always felt somewhat of a displaced person and once since I chose to live in Paris, city of displaced people, I have been able to feel as Argentine as I do, because I no longer have to put up with all the negative aspects of that country and am able to keep only those that I’m fond of. A notion, of course, highly comfortable, even a luxury, but I’ve paid for it by having put up with both incarnations of Peronism — its original populist, mildly-fascist one, and the second, senile, would-be Maoist farewell performance.

3

The second “homecoming” film, Boulevards du crépescule, is a personal essay, though one whose gaps and occasional ambiguities suggest at times some of the procedures of fiction. The film’s subtitle —

on Falconetti, Le Vigan and a few others

…

in Argentina

— accurately describes its subject. Yet the ellipsis of three periods, appearing on the screen in a separate line between “a few others’ and “in Argentina,” almost subliminally introduces a sense of indeterminacy at the same time that it evokes, appropriately, the title of Cozarinsky’s first film, where the rudiments of this indeterminacy are already established.

The key historical event of Boulevards, the “mirror-image” (or reverse-angle) of the event concluding One Man’s War, is the celebration of the liberation of Paris on August 24, 1944, in Buenos Aires’ Plaza Francia. The event is first evoked in the film by Adolfo Bioy Casares, then by Gloria Acorta, then by Cozarinsky himself, who notes other events occurring on the same day, including a performance by Falconetti in The Children’s Carnival at the Casa del Teatro. But it isn’t until roughly halfway through the film, after the same celebration is recalled by Andrée Tainsy, another actress who knew Falconetti in Buenos Aires, that Cozarinsky incidentally reveals that he too was present at the same event: “Hanging onto the hands of my parents, I did not understand people’s joy, nor their relief. I heard singing in a tongue that I did not yet understand.” Just before he speaks these words offscreen, over the offscreen voices of Tainsy and Acorta recalling the same event, we see Cozarinsky looking at an array of photographs spread out on a table. When he arrives at his own memomy to complement theirs, the camera moves forward to a boy in the crowd seen in one of the photographs — a specific image to go with his recollection. But is this boy in the photograph in fact Cozarinsky? We have no way of knowing, yet the fact that Cozarisnky immediately goes on to say, “Nevertheless, the child I was would grow up in a country seduced by some quite cheap illusions,” alerts us to the possibility that we have just been seduced by a cheap illusion ourselves.

A little later on, after the film’s focus has shifted from Falconetti to Robert Le Vigan — another French actor who spent his last years in Argentina,in his case escaping from the scorn and other repercussions of having been a Nazi collaborator — Cozarisnky plays an even more elaborate trick with his documentary materials. In the course of interviewing the writer Nestor Tirri, a casual neighbor of Le Vigan in Tandil who is recalling his fleeting impression of the man, the film suddenly cuts to footage of Le Vigan walking through the woods in the same town, seen from behind. Then we see Cozarinsky himself in front of the house in Tandil where Le Vigan lived for over fifteen years, interviewing two of his former neighbors about their own recollections. In the midst of their replies, he cuts to footage of Le Vigan at the same location, saying goodbye to his wife before taking a short stroll, and the voices of Cozarisnky and the neighbors are allowed to run over part of this footage. Still later, the film includes an actual interview with Le Vigan in Tandil and then shows Cozarinsky visiting the gravesite of both Le Vigan and his wife.

From one point of view, this coexistence of “past” and “present” tenses in the same locations is a standard documentary device. But to confess to a certain naïvité on my own part, my initial assumption in viewing this film was that Cozarisnky had employed an actor to play Le Vigan; it was only after I asked him about this that I discovered he had drawn on an earlier television interview with Le Vigan that had never been shown.

Part of the significance of my error is simply the propensity of viewers to produce their own images to correspond to events that are being recounted in films, regardless of whether the films in question are documentary or fiction. Yet the passivity of the usual film-viewing experience is such that if the film itself furnishes an image to “replace” the imagined one, the viewer is likely to accept that replacement without protest, either symbolically or literally. This is well illustrated by Cozarisnky’s interview with two former French students of Le Vigan, both of them women, which is held in a former Tandil movie theater that is now a discothèque. Cozarisnky informs us at the beginning of the interview that another former student of Le Vigan, the writer Jorge DiPaola, “would be joining us,” and the point at which he appears in the balcony, when one of the women below is describing to Cozarinsky Le Vigan’s plans to build a chicken coop, there is a brief moment or two when DiPaola becomes the figurative “stand-in,” or double, for Le Vigan himself.

Considering the degree to which Falconetti and Le Vigan are both presented to us as “lost” figures, historically speaking — formerly famous actors whose last years can only be dealt with in fragmentary glimpses and impressions, mainly through the accounts of people who knew them only slightly — it is we, in any case, who have to furnish most of the images, and the most that a documentary filmmaker can do in this process is to guide us in this activity. Yet as my initial example demonstrates, Cozarinsky as a young child in Plaza Francia on August 24, 1944 is every bit as inaccessible today, even to Cozarinsky himself. Acknowledging such a mystery is, properly speaking, the point at which his enterprise begins — the moment of calculated reticence when “cinema indirect” takes shape.

_______________________________________________________

Footnote

*Significantly, Cozarinsky’s own study of gossip (“Le récit indéfendable,” published in Communications No. 30, 1979) was developed under the tutelage of Barthes.

——————————————————————————————

— Film Comment, September-October 1995