From Cineaste, Spring 1996. — J.R.

A dozen years ago, when his second feature, Stranger Than Paradise, catapulted him to worldwide fame, Jim Jarmusch seemed at the height of arthouse fashion. Having already known him a little before then, I could tell that the extent to which he suddenly became a figurehead for the American independent cinema bemused him in certain ways. Given the aura of hip, glamorous downtown Manhattan culture that seemed to follow him everywhere, how could it not? I can still recall a New York Times profile a few years back that was so entranced by his image that it suggested that, simply because Jarmusch chose to live in the Bowery, that neighborhood automatically took on magical, transcendent properties.

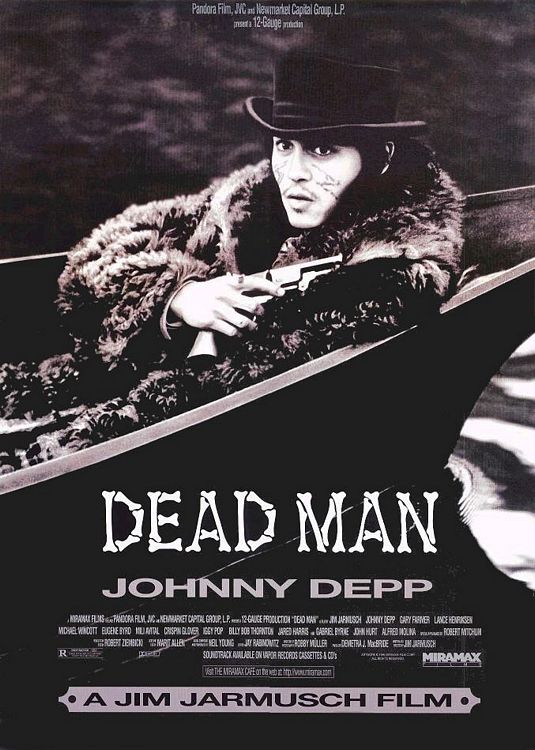

When Dead Man, his sixth feature, premiered at Cannes last year, it suddenly became apparent that Jarmusch’s honeymoon with the American press was over — although his international reputation to all appearances survives intact. There are multiple reasons for this, including Dead Man itself, and before getting around to this visionary, disturbing black-and-white Western — which I regard as his most impressive achievement to date — it’s worth considering what’s happened to the American independent cinema over the past decade, which has a lot to do with Jarmusch’s changed position in the media.

When thinking about today’s ambitious American filmmakers, one of the easiest ways to distinguish between Hollywood employees (current or prospective) and those with more creative freedom is to look for logical and consistent developments from one film to the next — a clear line of concerns that runs beyond fads and market developments. Though it’s possible to see a director such as Alfred Hitchcock developing certain formal and thematic ideas in his Fifties movies, there’s little likelihood of such an evolution being possible in a studio director today, what with agent packages, script bids, multiple rewrites, stars who get script approval and/or say over the final cut, test marketing, and so on. Within such a context, it’s significant that Jarmusch as a writer-director, virtually alone among American independents who make narrative features, owns the negatives of all his films. This means that, for better and for worse, all the developments — and nondevelopments — that have taken place in his work between Permanent Vacation (1980) and Dead Man are of his own making.

This provides one model of American independent filmmaking, but not the one that most of the media are currently preoccupied with. Their model tends to gravitate around the Sundance Film Festival, where success in the independent sector is typically defined as landing a big-time distributor and/or a studio contract — the exposure, in short, that goes hand in glove with dependence on large institutional backing. And though it would be wrong to assume that Jarmusch isn’t himself dependent on such forces to get his films into theaters (Miramax is distributing Dead Man), the salient difference between him and most other independents is that he’s strong enough to afford the luxury of brooking no creative interference when it comes to making production and postproduction decisions. (Dead Man has been trimmed since its Cannes premiere — without apparent injury, in my opinion — but all of the recutting was done without Miramax’s input.)

So where does Jarmusch belong in the present, reconfigured independent scene constructed around the Sundance myth? One disheartening clue is offered by Sundance star Kevin Smith, the director of Clerks and Mall Rats, who was recently quoted as saying, “I don’t feel that I have to go back and view European or other foreign films because I feel like these guys [i.e., Jarmusch and others] have already done it for me, and I’m getting filtered through them. That ethic works for me.” Another clue is provided by the mixed response of the American press to Dead Man at Cannes.

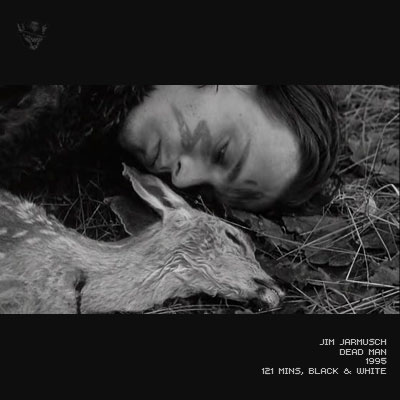

Prior to Dead Man, when Jarmusch’s three features since Stranger Than Paradise — Down By Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989), and Night on Earth (1992) — could be partially taken as light, comic entertainments with serious undertones, it was possible to assume that Jarmusch might have continued in such a vein. But Dead Man –– which might be described as a serious art film with comic elements — flings down the gauntlet of proposing a much more ambitious direction for Jarmusch’s work, daring an audience to follow it. The plot hinges on a recently orphaned accountant named William Blake (Johnny Depp) — though, characteristic of Jarmusch’s white heroes, he’s never even heard of the poet of that name — traveling out West with the promise of a job at a steelworks run by someone named Dickinson (Robert Mitchum in a cameo), only to discover that the position has already been taken. Soon afterwards, in bed with a woman named Thel Russell (Mill Avital), he suddenly finds himself killing her former lover (Gabriel Byrne), who happens to be Dickinson’s son, in self-defense just after he has shot her. Seriously wounded by a bullet in the same skirmish, Blake spends the remainder of the movie dying — mainly in the wilderness, and chiefly in the company of a renegade Native American named Nobody (Gary Farmer) as they proceed through various encounters with strangers, many of them bounty hunters dispatched by Dickinson and seeking a reward.

Even though Dead Man contains many familiar Jarmuschian elements — a “foreigner” (Nobody) who offers a poetic, comic critique on the viewpoint of the other characters (such as the fact that he knows the poetry of William Blake and Blake himself doesn’t); an episodic structure; a starting-and-stopping rhythm punctuated by fadeouts (hypnotic and haunting in this case, if one feels sympathetic to what the film is doing, and accompanied by a powerful and minimalist improvised Neil Young score); and a preoccupation with death (a constant in Jarmusch’s work since Down By Law) — this is the first substantial alteration of the Jarmusch formula since the one that took place between Permanent Vacation and Stranger Than Paradise, in large part because of the changes brought about by a period setting and a Hollywood genre (the Western). And the film’s carefully researched, multifaceted approach to various Native American cultures makes for a sobering contrast to the scary portrait of white America as a primitive, anarchic world of spiteful bounty hunters and bloody grudge matches — a portrait that can be read without much difficulty as contemporary.

Perhaps the film’s most courageous defiance of commercial conventions is a response to the current cinema of violence that is so unsettling that audiences generally can’t decide whether to wince or laugh. Every time someone fires a gun at someone else in this film, the gesture is awkward, unheroic, pathetic; it’s an act that leaves a mess and is deprived of any pretense at existential purity, creating a sense of embarrassment and overall discomfort in the viewer that is the reverse of what ensues from the highly estheticized forms of violence that have become de rigueur in commercial Hollywood ever since the heyday of Arthur Penn and Sam Peckinpah, and which have recently been revitalized by Tarantino, among others.

My phone interview with Jarmusch took place in April, eleven months after the Cannes premiere of Dead Man, and two months after I saw the film a few more times in its final form at the Rotterdam Film Festival. In part because we’d already discussed the film more casually the previous August, the interview often took the form of a conversation, with me offering some of my reactions to the film and then getting his responses to them. — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Cineaste: I know that the main passage from William Blake that Nobody quotes — “Every Night & every Morn/Some to Misery are Born…/Some are Born to sweet delight/Some are Born to Endless Night” — is from Auguries of Innocence. But I’ve heard you say that some lines are quoted from Proverbs of Hell, and I don’t recall any.

Jim Jarmusch: Nobody says, “The eagle never lost so much time as when he submitted to learn of the crow.” And when he and William Blake meet again toward the end of the film, he says, “Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.”

Cineaste: The funny thing is, they sounded like Indian sayings in the film.

Jarmusch: Yeah, that was the intention. Blake just walked into the script right before I was starting to write it. There were a bunch of other quotes that didn’t get into the film that seemed very Native American: “Expect poison from the standing water.” “What is now proved was once only imagin’d.” “The crow wish’d every thing was black, the owl that every thing was white.” And Nobody quotes from “The Everlasting Gospel” when they’re at the trading post: “The vision of Christ that thou dost see/Is my Vision’s Greatest Enemy.”

Cineaste: How long was the rough cut that Neil Young improvised his score to?

Jarmusch. Two and a half hours. He refused to have the film stop at any moment. He did that three times over a two-day period. Neil asked me to give him a list of places where I wanted music, and he used that as a kind of map, but he was really focused on the film, so the score kind of became his emotional reaction to the movie. Then Neil came to New York to premix the stuff and we thought in a few places we’d slide it around a little, but it almost never worked — in general it was married to where he played it.

Cineaste: Was your final editing influenced by what he did?

Jarmusch: No, oddly enough. Or maybe it was, subconsciously. The final movie is two hours long and very little of Neil’s music is missing, so we didn’t cut much where there was music. But it wasn’t a conscious decision.

Cineaste: One thing I really like about Dead Man is that it’s the one film of yours, apart from Stranger Than Paradise, that really establishes a rhythm all its own, one that’s not the rhythm of any other film. It seems that part of this has to do with the fadeouts.

Jarmusch: Yeah, I think you’re right. But I’m the worst person to analyze the stuff and I hate looking back at it. I unfortunately had to look at Stranger again recently to prepare the laserdisc release in the U.S., which was really painful; I hadn’t seen it since 1984. But I think there is something similar to them in that they do have very particular rhythms that seem to grow out of the stories themselves. It doesn’t seem imposed in the same way that it might in Down By Law or the more formally episodic ones. It does have a very odd rhythm. I think of it — and I don’t know if this is accurate at all, it’s just in my mind — as being closer to classical Japanese films rhythmically. We had that in the back of our minds while shooting, that scenes would resolve in and of themselves without being determined by the next incoming image.

Cineaste: When Blake is traveling west on the train and sees other passengers firing at buffalo, there’s a line that says “A million were killed last year.” Was there a year in which that many were actually shot?

Jarmusch: I think in 1875 well over a million were shot and the government was very supportive of this being done, because, “No buffalo, no Indians.” They were trying to get the railroad through and were having a lot of problems with the Lakota and different tribes. So that’s factual I even have in a book somewhere an etching or engraving of a train passing through the Great Plains with a lot of guys standing upright on the top of cars firing at these herds of buffalo, slaughtering them mindlessly.

Cineaste: I’ve heard that Nobody speaks four languages in the film — Blackfoot, Cree, Makah, and English. How did you write the Indian dialog?

Jarmusch: Well, Michelle Thrush, who’s in the film, spoke Cree and is Cree. We wrote some dialog together and then she translated it with someone else who was even more fluent.

Cineaste: As I recall, none of the native American dialog is subtitled.

Jarmusch: No, I didn’t want it subtitled. I wanted it to be a little gift for those people who understand the language. Also, the joke about tobacco is for indigenous American people. I hope the last line of the film, “But Nobody, I don’t smoke,” will be like a hilarious joke to them: ‘Oh man, this white man still doesn’t get it.’ …Makah was incredibly difficult; Gary [Farmer] had to learn it phonetically and read it off big cards. Even the Makah people had trouble, because it’s a really complicated language.

Cineaste: Why did you make Nobody half Blood as well as half Blackfoot?

Jarmusch: Well, I wanted to situate him as a Plains Indian, so I chose those two tribes that did intermix at certain points historically but also were at war with each other. So his parents in my mind were like Romeo and Juliet; there was even a reference to that in the original script.

Cineaste: The funny thing about the tobacco joke is that, like so much in the movie, I took it as a commentary on America right now. Like the fact that Dickinson hires three bounty hunters to go after Blake and then sends other people out, too. Kent Jones said to me that was like the way Hollywood studios hire screenwriters.

Jarmusch: [Laughing] Good point — that’s true. But to talk about tobacco, there were indigenous to North America some forty strains of tobacco that are far more powerful than anything we have now. I have a real respect for tobacco as a substance, and it just seems very funny how the Western attitude is, “Wow, people are addicted to this, think of all the money you can make off it.” For indigenous people here, it’s still a sacrament, it’s what you bring to someone’s house, it’s what you smoke when you pray. Our cultural advisor, Cathy, is a member of the Native American Church and even uses peyote ceremonially.

We used to go up on these hillsides sometimes early in the morning before shooting, usually with just the native people in the cast and crew, and pray and smoke. She’d put tobacco in a ceremonial pipe and pass it around, and you’d wash yourself with the smoke. She prays to each direction, to the sky, to the earth, to the plants and all the animals and animal spirits. And what cracked me up is, as soon as the ceremony was over, we’d be walking back down the hill and she’d be lighting up a Marlboro. She was very aware of the contradiction herself because I used to tease her about it.

Cineaste: It seems like a key exchange when Blake asks Thel why she has a loaded pistol and she says, “Cause this is America.” I believe you had a gun as a kid, didn’t you?

Jarmusch: I still have guns. And I’m not into killing living things, you know, but I’ll always have guns. It seems so ingrained in America, but — well, the country was built on an attempted genocide, anyway. Guns were completely necessary. I find it very odd that the amendment about the right to bear arms, laws that were written so long ago, still pertain and don’t get adjusted properly. Because the right to bear arms doesn’t mean automatic weaponry designed specifically for human combat. I think people should have the right to bear arms, but they should be limited as to what kinds of guns they can have.

Cineaste: In a recent essay about the dumbing down of American movies, Phillip Lopate writes, “Take Jim Jarmusch: a very gifted, intelligent filmmaker, who studied poetry at Columbia, yet he makes movie after movie about low-lifes who get smashed every night, make pilgrimages to Memphis where they are visited by Elvis’s ghost, shoot off guns and in general comport themselves in a somnambulistic, inarticulate, unconscious manner.”

Jarmusch: I don’t know, man. Once I was in a working-class restaurant in Rome with Roberto [Begnini] at lunchtime. They had long tables where you sit with other people. We sat down with these people in their blue work overalls, they were working in the street outside, and Roberto’s talking to them, and they started talking about Dante and Ariosto and twentieth-century Italian poets. Now, you go out to fucking Wyoming and go in a bar and mention the word poetry, and you’ll get a gun stuck up your ass. That’s the way America is. Whereas even guys who work in the street collecting garbage in Paris love nineteenth-century painting.

I don’t know, am I supposed to put on a false voice and say, “Here are the rare exceptions, and we should be like them?”

Cineaste: A subjective impression I had when I first saw Dead Man at Cannes is that it’s your first political film. The view of America is a lot darker than in your previous films.

Jarmusch: I think it is a lot darker. You know, you can define everything as being political and analyze it politically. So I don’t really know how to respond to that because it wasn’t a conscious kind of proselytizing. But I’m proud of the film because of the fact that on the surface it’s a very simple story and a simple metaphor that the physical life is this journey that we take. And I wanted that simple story, and that relationship between these two guys from different cultures who are both loners and lost and for whatever reasons are completely disoriented from their cultures. That’s the story for me, that’s what it’s about.

But at the same time, unlike my other films, the story invited me to have a lot of other themes that exist peripherally: violence, guns, American history, a sense of place, spirituality, William Blake and poetry, fame, outlaw status — all these things that are certainly part of the fabric of the film, that maybe unfortunately, at least for the distributors, work better when you’ve seen the film more than once. Because they’re subtle and they’re not intended to hit you over the head with a sledgehammer.

Cineaste: Incidentally, why is the smoke that you see coming from the Dickinson Steelworks animated?

Jarmusch: I wanted it to look more realistic, and I didn’t have enough budget to do that matte shot to my satisfaction, so the smoke looked kind of cartoonlike. But I couldn’t redo it and I didn’t want to not have the smoke.

Cineaste: In the Sixties and Seventies, there was an attempt at a sort of makeshift genre that might be called the Acid Western, associated with people like Monte Hellman, Dennis Hopper, Jim McBride, and Rudy Wurlitzer, as well as movies like Greaser’s Palace; Alex Cox tapped into something similar in the Eighties with Walker.

Jarmusch: Yeah, I think of them as peripheral Westerns.

Cineaste: Dead Man struck me as being a much-delayed fulfillment of that dream. Part of it has to do with certain literary ideas about the wilderness and traveling from the East to the West. And if you think of all the white people that Blake and Nobody run into, they all seem to fit into two categories — some version of capitalism or some version of the counterculture, sometimes the two mixed together.

Jarmusch: Yeah, they coexist somehow. And the counterculture is always repackaged and made into a product. It’s part of America. If you have a counterculture band, you put a name on it, you call them beatniks, and you can sell something — books or bebop. Or you label them as hippies and you can sell tie-dyed T-shirts.

Cineaste: But then there’s also Iggy Pop in a dress. What’s disturbing about Dead Man is that the whole sense of society — which is always pretty attenuated in your films to begin with — is pretty nightmarish whenever it turns up. And some of the film’s stylistic ruptures evoke Acid Westerns as well, like that creepy yet strangely beautiful moment when the bounty hunter, Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen), crushes the head of a dead marshal under his heel, as if it were a rotten watermelon. Was that a homage to Sam Raimi?

Jarmusch: Not specifically Sam Raimi, but I was aware of that genre of films, whether it be something from The Evil Dead or even Raul Ruiz. I was definitely conscious that it was somewhat out of style in relation to my previous films, and maybe this film, too, but I left it in. It’s stylistically over the top, but it seems to fit with that guy’s character. The cannibalism, too, is over the top.

Cineaste: You get the feeling that between these isolated outposts of civilization, anything can happen. You can’t always distinguish between what’s interior and what’s exterior, what’s real and what’s inside your head.

Jarmusch: Yeah. And I think when Blake encounters the trappers [Iggy Pop, Jared Harris and Billy Bob Thornton], it’s the same thing. It’s like here is a trace element of the family unit that has gotten so perverted out here, because these guys live out in the fuckin’ nowhere. Yet there’s some slight thread of a family unit that they’ve adapted between themselves — which is absurd on one level, but on another level it’s exactly what you’re saying. They’re way out there.

I don’t know if you can hear it, but when Iggy’s trying to load his shotgun, he’s complaining, “I cooked, I cleaned…” Incidentally, I recently came across this interesting Sam Peckinpah quote: “The Western is a universal frame within which it’s possible to comment on today.” Of course, I only saw this quote after I made the film.

Cineaste: I’m reminded of that 1972 Robert Aldrich Western, Ulzana’s Raid, which a lot of people said at the time was really about the war in Vietnam.

Jarmusch: In Hollywood Westerns even in the Thirties and Forties, history was mythologized to accommodate some kind of moral code. And what really affects me deeply is when you see it taken to the extent where Native Americans become mythical people. I think it’s in The Searchers where John Ford had some Indians who were supposedly Commanche, but he cast Navajos who spoke Navajo. It’s kind of like saying, “Yes, I know they are supposed to be French people, but I could only get Germans, and no one will know the difference.”

It’s really close to apartheid in America. The people in power will do whatever they can to maintain that, and TV and movies are perfect ways to keep people stupid and brainwashed. In regards to Dead Man, I just wanted to make an Indian character who wasn’t either A) the savage that must be eliminated, the force of nature that’s blocking the way for industrial progress, or B) the noble innocent that knows all and is another cliché. I wanted him to be a complicated human being.

Cineaste: Right, but he’s an outsider too, even to his own tribe. And given where we’re at in terms of Native American consciousness, it somehow seems significant that in order to give him coherence, you have to route him through Europe.

Jarmusch: I don’t know. Like the slaughtering of buffalo, that was based on real accounts that I read. I read accounts of natives that were taken all the way to Europe and put on display in London and Paris, and paraded like animals. I also read accounts of chiefs that were taken east and then murdered by their own tribes when they got back because of the stories they told about the white man — which becomes part of Nobody’s story.

Cineaste: The notion of what Nobody calls “passing through the mirror” seems to have a lot to do with the way the movie is structured: there’s the industrial town at the beginning and the Native American settlement at the end, the train ride and the boat ride…

Jarmusch: Yeah, and they do somehow connect with that abstract idea that Nobody has to pass Blake through this mirror of water and send him back to the spirit level of the world. But what was more fascinating to me is that these cultures coexisted only so briefly, and then the industrialized one eliminated the aboriginal culture. Those specific Northwest tribes existed for thousands of years and then they were wiped out in much less than a hundred years. They even used biological warfare, giving them infected blankets and all kinds of stuff — any way to get rid of them. And then they were gone. And it was such an incredibly rich culture.

I don’t really know of any fiction film where you see a Pacific Northwest culture. I know there’s the film The Land of the War Canoes made by Edward Curtis, the early twentieth-century photographer — he shot some Kwakiutl people, but it’s sort of a Nanook of the North deal where he used them pretty much as actors. But their culture was so rich because where they lived provided them with salmon, and they could smoke that and exist all winter long without having to hunt very much. Therefore they spent a lot of time developing their architecture, their carving, their mythology, and their incredibly elaborate ceremonies with these gigantic figures that would transform from one thing into another, with all kinds of optical illusions and tricks. That’s why the long house opens that way in Dead Man, when Nobody goes inside to talk to the elders of the tribe and eventually gets a sea canoe from them. It seems to open magically, but it’s based on a real system of pulleys that these tribes used.

Cineaste: It’s interesting how Blake picks up bits and pieces of his identity from other people in the film, including Nobody.

Jarmusch: Yeah. He’s also like a blank piece of paper that everyone wants to write all over, which is why I like Johnny [Depp] so much as the actor for that character, because he has that quality. He’s branded an outlaw totally against his character, and he’s told he’s this great poet and he doesn’t know what the hell this crazy Indian guy is even talking about. Even the scene in the trading post where the missionary [Alfred Molina] says, “Can I have your autograph?” and then pulls a gun on him, and Blake stabs him in the hand and says, “There, that’s my autograph.” It’s like all these things are projected onto him.

When Nobody leaves him alone after taking peyote, Blake is left to go on his own vision quest briefly, whether he knows it or not, because he’s fasting — not because he wants to but because he doesn’t know how to eat out there. That’s a really important ceremony of most North American tribes — a vision quest where you’re left alone to fast, usually for a three-day period.

Cineaste: How many Native Americans have seen Dead Man so far?

Jarmusch: At this point very few. But it’s going to show in Taos, and I know there’s a big Native American contingency that goes there. Gary Farmer’s having a benefit in Canada, and I’m going to take the film eventually to the Makah reservation to show them. And then Gary and I are going to make sure that videos are distributed to every reservation video store we can get them in. That’s really important to us.