It seems that I wrote (or completed) this in October 1999, for the American Movie Classics monthly magazine (I don’t recall which issue). — J.R.

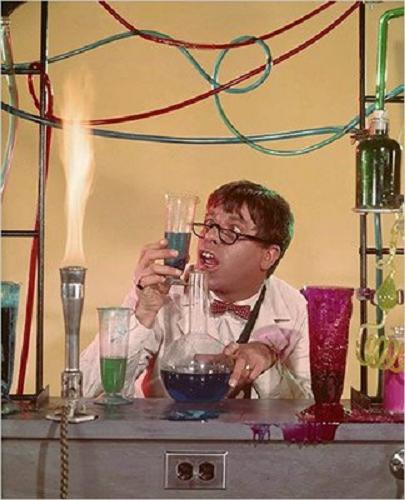

The Nutty Professor (1963) — Jerry Lewis’s fourth and in some ways best constructed feature as writer-director-performer — is one of the finest versions of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story that we have, and not only because it happens to be the funniest. (It’s also the one with the best music: Les Brown’s band, and memorable versions of both “Stella by Starlight” and “That Old Black Magic”.) A good deal subtler than the raucous Eddie Murphy remake (1996), it illustrates the troubling perception that most of us prefer egotistical bullies to shy, sweet-tempered klutzes. It also provides us with an excellent opportunity for reassessing a multifaceted artist who has seldom received his due in this country.

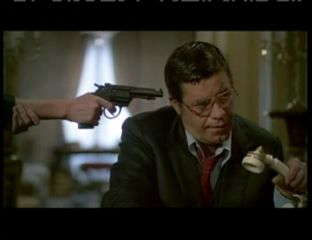

Critical opinion has often described the overbearing Buddy Love, Lewis’s Mr. Hyde, as a reincarnation of Dean Martin, six years after the decisive breakup of the Martin and Lewis duo. Superficially this sounds like an ingenious notion, but in fact it misses the mark. Part of what’s so disturbing about Buddy Love — making his belated entrance about a third of the way through The Nutty Professor as a romantic stand-in for Julius Kelp, Lewis’s bumbling version of Dr. Jekyll — is that Lewis clearly knows him like the back of his hand. The movie’s spirit is much closer to autocritique than it is to revenge, and when Lewis went on to play another caustic version of himself twenty years later — an unpleasant talkshow host in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy — the relation of Jerry Langford to Buddy Love bordered on the uncanny.

If it’s the duty of comic performers to make us feel comfortable with ourselves — with our social skills, our confidence and authority in confronting the world, and our capacity to think and behave like adults, not to mention the existence and coordination of our own bodies — then Lewis has to be regarded as a failure. But it might be argued that all the greatest screen comics — Chaplin, Keaton, Tati, Laurel and Hardy, and indeed Lewis — delve to some degree in our discomforts and uncertainties. Even the more verbally oriented funnymen like Bob Hope and Woody Allen, protected by a certain smirking superiority to their derisive targets, derive part of their humor from their status as fall guys and their pathos as losers, though they never threaten us in the same way that Lewis does.

It seems that American taste in movie comedy is periodically subject to bouts of amnesia. Memories of Charlie Chaplin’s American fame between the teens and the mid-1940s often elide the fact that the U.S. government, with the support of the press, forced him into exile during the 1950s because of his leftist politics and his sexual behavior. American disenchantment with Lewis between the 1960s and the present hasn’t been quite so harsh or as punitive as that, but it’s displayed a similar evolution from unreasoning infatuation to an equally irrational rejection. This isn’t of course to claim that a significant number of diehard Jerry fans don’t remain today, as evidenced, among other things, by the highly successful recent tour of Damn Yankees. But the fact that Lewis starred in this stage musical as the Devil — a character with a distinct relation to Buddy Love — helps to pinpoint the troubled place he continues to hold in the American imagination.

Maybe this is because Lewis gets under our skins by revealing too much. Part of the 1950s animus against Chaplin stemmed from the fact that he wasn’t American; and I suspect that much of the post-1950s animus against Lewis stems from an unconscious perception that he shows the world just how embarrassing being an American can be. Adolescent brashness and hysteria, nouveau riche vulgarity, sexual panic, and social maladroitness combined with an aggressive compulsion to perform Good Works: it’s an exceptionally creepy portrait of the American loudmouth abroad, the boorish yahoo set loose in the world, and no one displays it as vividly or as consistently as Lewis does.

So it becomes easy for us to forget that an estimated 80 million people saw Sailor Beware (1951), Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis’s fourth feature, and that their ninth, Living It Up (1953), made more money than Singin’ in the Rain, On the Waterfront, or The African Queen. The fact that the monster impact of Martin and Lewis on American society of the 1950s briefly preceded that of Elvis Presley improbably suggests that, in their own manic fashion, Dean and Jerry helped to usher in the youth culture of the 1950s. (Lewis’s best French critic, the late Robert Benayoun, pointedly entitled his first major piece about him “Simple Simon, or the Anti-James Dean”.)

Relative to this impact, there’s little point in speaking about the alleged French craze for Lewis, which peaked over two decades ago and never came close to equaling his early American fame. According to Lewis himself, he’s more popular these days in Australia, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Spain than he is in France. And to give some notion of how his French reputation has faded, let me cite a recent personal experience. When a trendy French rock weekly ran an interview with me about American movies in 1997, this was prefaced by a banner describing me in part — just to show how iconoclastic I was — as an “original critic who prefers Jerry Lewis to Woody Allen.”

Back when there was something of a French vogue for Jerry in the 1960s and 1970s, maybe it was the French trait of respecting Lewis as a technically and formally innovative film director and as a highly inventive writer that outraged Americans. But strange as such an attitude might appear to some, it was Lewis in fact who invented the video assist on his first feature as a director — the idea of mounting a small video camera beneath the movie camera and connecting it to a closed-circuit monitor, used by most commercial directors in the world today.

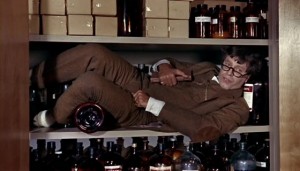

The French critics were also more careful than their American counterparts to distinguish between the Lewis comedies directed by Lewis and those directed by his comic mentor, Frank Tashlin. Tashlin, a former cartoonist who transposed his taste for loud colors to movies, was a conscious satirist of the excesses of American culture who used Lewis to make many of his best points. (A good example of Tashlin’s vigorous style can be found in The Disorderly Orderly, released one year after The Nutty Professor and also showing on AMC this month.) By contrast, Lewis as a director is usually more psychological and abstract, more open to ideas that are strange and nightmarish than to social criticism. Yet one finds some vestiges of Tashlin’s influence in The Nutty Professor‘s erotic voltage (expended here on the winsome Stella Stevens — in contrast to Tashlin’s emphasis on opulent 50s goddesses such as Jane Russell and Jayne Mansfield) and in the garish comic book colors. What remains pure Lewis is the manic-depressive mood swings between Kelp and Love — a kind of terrifying contrast between perpetual victim and perpetual victimizer, and a marriage of opposites that threatens to explode.