From The Soho News, July 18, 1980. Also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995). — J.R.

John Cassavetes, Filmmaker and Actor Museum of Modern Art, 20 June — 11 July

Nineteen years ago, when I was a high school senior making one of those boring, difficult adolescent transitions — from being a social outcast in my hometown in the Deep South to being a social outcast as a southerner at a New England prep school — I had the good fortune to discover John Cassavetes’s SHADOWS at the New Embassy at Broadway and 46th. It was near the beginning of my spring vacation, which meant that I could return to this movie again and again, during the same week or so when I was getting my first looks at BREATHLESS, THE RULES OF THE GAME, ROOM AT THE TOP, SPARTACUS, THE MISFITS, and TAKE A GIANT STEP.

Art in our time, Harold Rosenberg once wrote, appeals either to other artists or “to introverted adolescents, to people in crises of metamorphosis, a small-town girl who has met an intellectual, a husband forced to give up drinking, a business man who feels spiritually falsified, all these being, like the audience of artists, more attentive to themselves than to the work.” And D. W. Griffith, Annette Michelson once reminded us, was a contemporary of Picasso. So it shouldn’t be all that curious to see simultaneous retrospectives of two artists, Picasso and Cassavetes (a contemporary of Jackson Pollock), at MOMA this month.

Back in 1961, in a $40,000 movie called SHADOWS, there was a warmth in what happened between people that could bring me close to tears. Part of this was an incestual warmth between siblings — played by Hugh Hurd, Lelia Goldoni, and Ben Carruthers — that reminded me of J. D. Salinger’s Glass family, another team of neurotic actors. But it was a warmth that went further (and was more radical, I thought) by being interracial as well as incestual, and it had none of the hard crust of Salinger’s New Yorker upper-class snobbery.

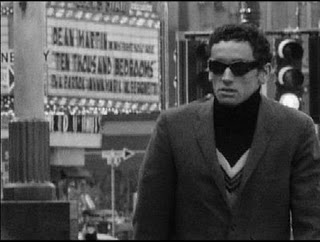

There was also Charles Mingus’s lovely, plaintive jazz score, offering a similarly unbridled emotional nuzzle. I soon grew to cherish every sign of vulnerability that the movie wore on its tattered sleeve — even the misspelling of “saxophone” in the opening credits, or the much-discussed closing title (“The film you have just seen was an improvisation”), accompanied by a ShafI Hadi sax solo, which appeared over Carruthers walking aimlessly past the old Colony Record Shop on 49th, not far from Birdland.

These signs of vulnerability ranged from effective/cornball Method riffs — like Tony Ray pausing just a beat between two words in his seduction of Lelia (“You’ve got the softest lips I’ve ever…felt”) — to more subtle stuff between a would-be nightclub crooner (Hurd) and his would-be manager (Rupert Crosse), so delicately and sweetly nuanced that it became a veritable lesson in ways that people could behave decently toward one another. (If a certain amount of crude, anti-intellectual bullying turned up in other sequences, this could easily be overlooked.)

I was such a good pupil that the following year, when I was a freshman at New York University (NYU), I went all the way to the Brooklyn Paramount to get my first look at Cassavetes’s second film, TOO LATE BLUES, made in Hollywood. A flawed, mawkish, and fitfully beautiful film about jazz musicians with Bobby Darin, Stella Stevens, and the unforgettable Everett Chambers, it was getting lambasted by practically every critic in sight, yet still had some improbable powerful moments — both musical and actorly — in the midst of all its bathos. And a year later, I saw Cassavetes’s other abortive Hollywood project, A CHILD IS WAITING, back in my hometown.

Five more years passed before FACES premiered at the New York Film Festival. If, as one of Rosenberg’s introverted adolescents, I was mainly attentive to SHADOWS for all the things it said about me, I’m sure that many other, differently oriented spectators were seized by Cassavetes’s first commercial hit in precisely the same way. Despite the loss of the jazz motif in Cassavetes’s subsequent work, the new crop of buffs — like me in 1961 and 1962 — were all too happy to confuse “freedom” and “reality” with whatever had been socially repressed in them. And so it has gone, with diverse peaks and valleys, in the five features directed by Cassavetes since FACES: HUSBANDS, MINNIE AND MOSKOWITZ, A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE, THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE, and OPENING NIGHT.

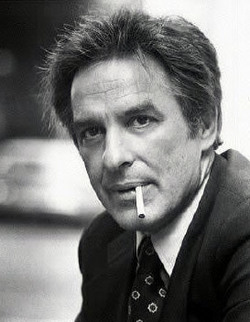

As Picasso has his blue and pink periods, Cassavetes as a director can be said to have his jazz and Gena Rowlands periods — the latter cycle encompassing everything from A CHILD IS WAITING to OPENING NIGHT except for HUSBANDS and THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE, the only films not featuring Cassavetes’s talented wife. As an actor, he seems to have only one period, black and white, although he’s usually most effective as a straight villain — think of ROSEMARY’S BABY and THE FURY. The latter film and Elaine May’s abrasively brilliant MIKEY AND NICKY are two unfortunate omissions in the museum’s season, which otherwise seems satisfyingly full: all nine of his directed films, and as many independent samples of his career as an actor (including some television work).

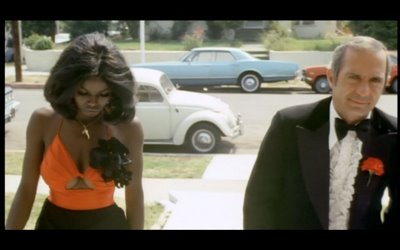

In their very different ways, HUSBANDS and THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE show Cassavetes at his most freakishly mannerist. The loutish, self-ingratiated misogyny in the former was so offensive to me when I saw it several years ago that it threatened to make me swear off Cassavetes forever. (Earlier this year, reading Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, I was unpleasantly reminded of HUSBANDS, threatening to swear off Bellow forever.) Softer and more charismatic, THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE is an unexpected genre film that, even more unexpectedly, turns out to be a kind of personal testament, a film that movingly sums up Cassavetes’s sloppy, lovable, stupid brand of humanity and cinema — underlined by hero Ben Gazzara’s theme song, “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” — as succinctly as THE TESTAMENT OF ORPHEUS sums up Cocteau’s.

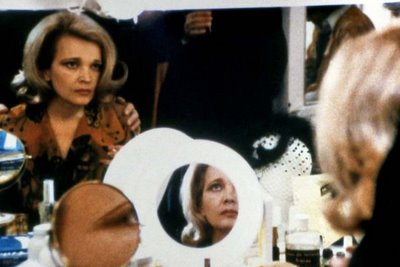

What are we ever going to do with a temperament as brutally obstinate, as sprawling and unwieldy, as Cassavetes’s except turn it into a Rorschach test for our own passionate forms of vanity, a sounding-brass for the tyranny of our own precious sensitivity? Yet like any obsessive fisherman who casts his nets wide — a Whitman, O’Neill, Pollock, Mingus or any other stammering, hollering counterpart — he occasionally comes up with some pretty fancy catches. His latest film, OPENING NIGHT — the first Cassavetes film about an actor, with a virtuoso performance by Rowlands — pushes forward a kind of frenzied psychodrama already set forth by A WOMAN UNDER THE INFLUENCE, which, in turn, repeats a narrative event — a woman attempting suicide in a man’s presence — already seen in TOO LATE BLUES and FACES.

For many critics, the height of absurdity in TOO LATE BLUES is reached when Bobby Darin forces Stella Stevens’s face into a sink after such an attempt, and there is a sudden cut to her face under the faucet as seen from the vantage point of the sink drain. Cassavetes’s refusal to tear away from an actress’s face at a crucial moment, regardless of all the technical gaucheries and jeers that this will cost him, is largely what his awful, irritating integrity is all about. Tons of it can be seen in MOMA’s retrospective.