From the December 1981 issue of American Film. I was quite unhappy with the way this article was edited at the time, but having discovered my original submitted draft quite recently (in mid-November 2011, 30 years later), I’ve decided to resurrect it here, including my own title. (Theirs was “Looking for Nicholas Ray”.)

My working assumption in restoring original drafts on this site, or some approximation thereof, isn’t that my editors were always or invariably wrong, or that my editorial decisions today are necessarily superior, but, rather, an attempt to historicize and bear witness to my original intentions. It was a similar impulse that led me to undo some of the editorial changes made in the submitted manuscript of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), when I was afforded the opportunity to reconsider them for the book’s second edition 15 years later (available online here) — not to revise or rethink my decisions in relation to my subsequent taste but to bring the book closer to what I originally had in mind in 1980. — J.R.

By and large, the last three decades in the life of film director Nicholas Ray can be divided fairly evenly into three distinct parts. From 1948 to 1958 he directed his first seventeen features, from They Live by Night to Party Girl -– a body of work that includes such films as In a Lonely Place (1950), On Dangerous Ground (1952), Johnny Guitar (1954), Rebel without a Cause (1955), and Bigger Than Life (1956).

Then, from 1959 to 1969, Ray lived mainly in Europe, where he directed his last three commercial features, all of them in 70 mm: a film about Eskimos shot in the Canadian arctic, Greenland, and British and Italian studios (The Savage Innocents, 1959), and two spectaculars produced by Samuel Bronstein in Spain, King of Kings (1961) and 55 Days at Peking (1963).

Ray’s last ten years, 1969, to 1979, were spent mostly back in the United States, during which time he brought only one feature anywhere close to completion: the unorthodox We Can’t Go Home Again, made with college students. (Lightning Over Water — a film about his last months on which he collaborated with young German director Wim Wenders – was edited only after his death.)

What actually happened to Nick Ray, during the sixteen long years that passed between his collapse from a major coronary during the shooting of 55 Days at Peking (which was finished by second-unit directors) and his eventual death from brain cancer? For that matter, what about his prodigious early careers in theater (with Elia Kazan), radio (with John Houseman), and folk song musicology (with Alan Lomax), after studying architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright – not to mention diverse kinds of administrative government work? (While working for the Office of War Information during World War II, he gave painter and film critic Manny Farber his first job, as a “rejuvenator” of toys.)

For better and for worse, the many wanderings and projects of Ray’s life have long been the stuff of legends. Ray has been sentimentalized, vilified, analyzed, worshiped, dismissed and debated for what he was and did to such a degree that it has become difficult to hold him in any close focus or to see him whole. Attempting to learn a few things about certain segments of his last years has been a fascinating yet frustrating task, for no two viewpoints of the man ever quite coincide. What is astonishing, in view of his excesses, is the generosity he often provoked in others.

Like the myths circulated about immoderate poets ranging from Arthur Rimbaud to Dylan Thomas and jazz musicians ranging from Bix Beiderbecke to Charlie Parker, the trail of tall tales that has followed in the wake of Nick Ray has continued to haunt the film community as a whole on both sides of the Atlantic. In part because Ray was lionized by many, considered a social undesirable by many others, and himself actively sought and relished the role of outlaw and maverick, he carved out a rather outsized profile during his final years that perhaps no film of his, finished or otherwise, could have expressed or contained. For fourteen years, one might say he directed films that were bigger than life. After that, Ray mainly led a life that was at once larger and smaller than the films he didn’t direct.

***

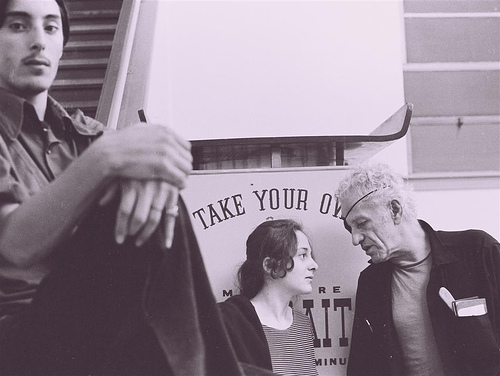

The first time I met Ray was at the Paris Cinémathèque in the spring of 1973. This was at a private screening of the unfinished We Can’t Go Home Again, made with several students at Harpur College in Binghamton, New York -– a radical, multi-image statement of political alienation, filmed in 8mm, Super-8, 16mm, Super-16, and 35mm, whose images are combined with a video synthesizer for most of its duration into one crowded fresco. I saw him again when he showed the film at the Cannes Film Festival shortly afterwards, to a mainly bewildered response.

Then, late one rainy morning in Paris, walking past the Café aux Deux Magots, I found him huddled in front, getting completely soaked and looking rather pathetic. I had already heard talk about the quantities of alcohol and amphetamine he had recently been consuming, and they had both visibly taken their toll. Wearing a black eye patch over his right eye — whose sight had been lost due to an embolism he had suffered in Chicago a few years earlier, while filming portions of the 1969 Conspiracy Trial for a never-completed project — he seemed more vulnerable than ever at 61, and virtually a derelict.

There seemed to be only one thing to do. I invited him inside for a drink; he warmly accepted, and promptly ordered a tequila with a beer chaser. I was in the midst of writing an article about him at the time [for Sight and Sound], and was full of questions I wanted to ask. Yet despite his friendliness and willingness to help, most of my queries were met with protracted pauses and blank stares.

Having grown up in a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in Alabama, and knowing that Ray had studied with Wright at the latter’s Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin in the early Thirties, I was eager to get Ray’s impressions of the man. But my efforts to pry any responses at all out of him were in vain. I felt like a safecracker at work without the right combination.

I had better luck when I mentioned having attended Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee – a radical stronghold he had known well in the Thirties, when it had centered on organizing labor, and I had known in the early Sixties when its focus was civil rights. (The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the use of “We Shall Overcome” as a movement anthem had both taken shape there.) But, as in many such encounters, we devoted most of our conversation to hunting for such links rather than knowing what to do with them once we’d found them. In addition, he spoke so slowly and haltingly that it was hard to know at times when he had finished saying something.

The conversation turned to his films. I remarked on what a pity it was that he had never directed a musical, considering how closely certain moments in his films seemed to verge on that form: James Dean’s knife-fight outside the planetarium in Rebel Without a Cause, for instance, which reminded me of something like West Side Story. He replied that, in fact, the idea of making a modern-dress musical out of Romeo and Juliet had been a dream of his long before West Side Story had ever taken shape.

I’m sure that my conversation with Ray was prototypical of countless ones that he had with young admirers over the years. Some of the original fans had, of course, been members of the New Wave – Godard, Truffaut, Rivette. Rohmer and others in the Fifties – which had filled the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma with extravagant panegyrics for the personal passion they had found in Ray’s movies, forged like a swirling, macho signature into the corporate studio styles of Columbia, Fox, MGM, Paramount, Republic, RKO and Warners. Prior to that, a generation of young English critics, headed by Penelope Houston and Gavin Lambert (who later worked for Ray as a scriptwriter), had applauded his debut as a film director at age 37, in They Live By Night –- which, like the subsequent Rebel Without a Cause, dealt with a romantic teenage couple on the run.

When he got up to leave, Ray invited me to accompany him to the novelist James Jones’ place on the Île St.-Louis; I regretfully had to decline due to a prior commitment. It was still raining fitfully along Boulevard St.-Germain as we walked together for several blocks, in the direction of Boulevard St.-Michel. I offered the shelter of my umbrella, but he politely refused, saying that he had a phobia about umbrellas and their pointed ends because of his single eye.

I later discovered that my conversation with Ray was typical of countless ones he had had with young admirers over the years, when his responses were often minimal or separated by protracted pauses. His early fans included members of the French New Wave -– Godard, Rivette, Truffaut, Rohmer, and others –- who in the fifties filled the pages of Cahiers du Cinéma with extravagant panegyrics for the personal passion they found in Ray’s movies, scrawled like a swirling signature across the studio stamps of Columbia, Fox, MGM, Paramount, Republic, RKO, and Warners. Prior to that, a generation of young English critics, headed by Penelope Houston and Gavin Lambert (who later worked for Ray as a scriptwriter), had applauded his debut as a film director, at age thirty-seven, with They Live By Night –- which, like the subsequent Rebel Without a Cause, dealt with a romantic teenage couple on the run.

***

“He was a terrible ham – a lousy actor,” I was recently told by critic Myron Meisel, who directed Ray in some sequences of I’m a Stranger Here Myself (1974) – a documentary portrait of Ray whose title comes from a line delivered by Sterling Hayden in Johnny Guitar. “He could be very good if you were strict with him; otherwise he’d get very flamboyant. And he had no sense of rhythm as an actor,” Meisel went on, reminding me of Ray’s slow speech patterns. “Editing was another matter. Put him on a movieola and he had great rhythm – it was all in the feet.”

“He had a marvelous charisma as a speaker,” I heard from László Benedek, director of The Wild One and four years Ray’s senior, who knew him from the time that they were both directing their first features in Hollywood, and met at Gene Kelly’s house. (Nearly thirty years later, as chairman of the graduate film department at New York University’s School of the Arts, he hired Ray to teach directing courses.) “He knew how to be surprising, and I often teased him about that – that when he was asked something, he started saying a sentence and then broke it off and there was a long, long pause. And I said, ‘You know, you can’t kid me, you are faking that. Because after a long pause, anything you say sounds deep and brilliantly formulated!”

Shortly after I saw Ray in Paris, he directed and acted in a semicoherent avant-garde sketch about a theater janitor for a Dutch movie called Erotic Dreams, but then wasn’t able to edit the results. The following fall, when he was back in the United States on the East Coast, Tom Luddy of Pacific Film Archives in Berkeley invited him out to California for a retrospective of his films. “He came out for three weeks,” Luddy recalls, “and then it became apparent that he had no place to go, and that he wasn’t returning to where I’d invited him from, and he felt like staying. So he stayed on, and we helped him stay on.”

Eventually, Ray had the uncompleted We Can’t Go Home Again shipped out west. Then, as Luddy tells it, “two guys showed up, students, and talked Francis [Coppola] into giving them the editing rooms of The Conversation from midnight to eight in the morning. And Nick would sleep in the screening rooms at Zoetrope in the daytime, and then emerge around midnight to edit We Can’t Go Home Again on Francis’s machines.”

Over the next month or so, however, many problems cropped up. The old Zoetrope was in a warehouse district of San Francisco, and had a very complicated burglar alarm system that had to be disengaged every time someone went out between midnight and eight. “And whenever Nick went out for drinks and stuff, he always managed to trip the burglar alarm,” recalls Luddy, who works today as special projects director for Coppola’s Zoetrope. “Every time it cost money. And large expenses started appearing on phone calls made between midnight and eight, and the burglar alarm kept going off, and then the editing machine broke and the editors complained, and it became impossible for Francis to support him there.”

Luddy spoke next with a collective called Cine Manifest — a group that later went on to make the independent feature Northern Lights — which was also located in the warehouse district. “I was minimizing to them the problems they would encounter with Nick and encouraged them to help him. They had an extra space, and they allowed him to have a couch there and an editing table. Hr continued working there for a while, and it didn’t work out too well: disorderliness, chaos, drinking. I used to go back there to see him, and he’d be zonked out with a gallon of White Almadèn Mountain Rhine wine. Things would break — he’d get into funny situations with things like keys and doors.

“Then he managed to find a situation in Sausalito for a while which was very odd. It was a big warehouse space with sewing machines and seamstresses, and in the middle of this — there were no partitions — was suddenly a couch, a refrigerator, an editing table, tins of film, and Nick Ray. Right in the middle of a clothing factory!

“Nick would sometimes sit there nearly passed out and say, ‘Tom, you don’t know where I can find $36,000 do you?’ I’d say, ‘No, Nick, you asked about that last night.’ And he’d say, ‘How about six dollars? If I had six dollars, I could buy a hamburger and a bottle of Almadèn.'” “On and off,” László Benedek told me, “drinking was always a problem with him. There was also a lot of talk about drugs – I have no knowledge of that whatsoever. But drinking was a problem practically all along his career.”

Ultimately, Luddy once again helped Ray to relocate himself, this time through a friend in Los Angeles who worked in a lab that agreed to extend Ray credit. “Finally it got really out of hand and they stopped, I think, and wouldn’t release any of the material until they paid some of the bills.” The lab in question, CFI, stills holds a print of the film today. Susan Ray, the director’s widow, owns another, and has been trying to raise money to complete the film.

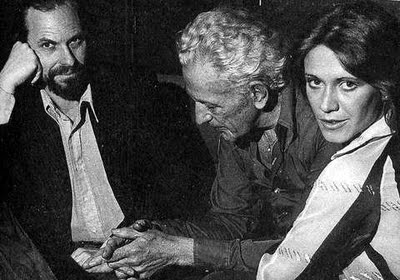

“When I first saw We Can’t Go Home Again,” Wim Wenders told me, “Nick showed it to me on an editing table. (Wenders was editing his film The American Friend at the time, in which Ray played the part of an art forger.) “I thought it was pretty revolting. I mean, I was shocked by the amateurish aspect of it. Also the sense of destruction that was in there — both together.”

“Since then, I’ve seen it six or seven times,” Wenders went on to say. “Finally I got to see a new print — at least the image was new, the sound track is just as lousy as ever — where the image is really brilliant and absolutely mind-blowing. You just have to imagine the sound in order to appreciate it, and realize just what a great movie is hidden in there. Not even hidden, it’s there — you see it.”

***

There are many standard Nick Ray stories that make the rounds. One involves Ray driving a car in Paris’s Latin Quarter during the student uprisings of May ’68 and picking up a couple of radicals. At one point, goes the story, he reaches into his glove compartment, pulls out a gun, and says, “James Dean gave this to me, and I’m passing it on to you because you’ll know what to do with it.”

Another story is that in the very last shot of Rebel Without a Cause, after all the characters have gone, the lone figure who’s glimpsed walking up to the planetarium is Ray himself. “You think it’s the astronomer, but actually it’s Nick,” Wenders said. “At least he told me it was him. In a way, it’s no different from his appearance in We Can’t Go Home Again, trying to kill himself twice. It is in a way on the same level. Because it is totally different from the walk-ons Hitchcock would do. It made me realize how highly private, or, rather, personal his films always were.”

“To what extent was We Can’t Go Home Again a collective film?” I asked Tom Farrell, one of Ray’s students in Binghamton who worked on the film — and who also served in several capacities on Lightning Over Water, including as an actor.

“Well, Nick was the guiding light because we were all students. It was all new to us, we listened to him because of his experience. We were all in awe of him, at least for a time, and then gradually people got turned off by Nick’s megalomania. He had a free labor pool, you know, and at the beginning everyone was willing to work all day long. But he took advantage, he was asking too much of everyone.”

Despite these and other misgivings, Farrell recalls some work on the film as a strong and positive experience, akin in certain respects to psychodrama: “In a lot of the film we were able to express really personal things. We had that audience, and it was a kind of psychological healing. I can’t explain it – he was able to bring it out of you, in mysterious ways.” “Just as with actors who worked with him in Hollywood,” Benedek told me, “there was a following at NYU who understood and admired Nick and remembered every single thing that he said.”

Farrell recollects when, in a fit of personal and political anguish, shortly after the Democratic National Convention in Miami in 1972, he decided to shave off his beard, and Ray decided to film him in the act of doing it. “I said, ‘You’re crazy, no one ever did anything like that.’ I had no idea I was going to cry or anything, but then, with all this mood he created on the set, I went into this womb of intensity. And I looked into the mirror and said, ‘That’s me.’”

Wenders spoke to me about Ray’s own final sequence in Lightning Over Water, a ten-minute closeup that runs for an entire reel and was completely improvised on the spot, with a similar kind of wonder. “During the shot he made up his mind that this was the end for him on the movie, that he didn’t want to go on, and he got it together once more. And I think for me, still, whenever I see that shot, it is the most daring thing he has done in the whole movie — or that anyone has ever done for me, in front of a camera, ever.”

“I think in America there is a certain puritanism that an artist has to comply with,” Chris Sievernich, the German producer of Lightning Over Water, told me. “It’s reflected in contracts — you can get fired for being drunk or for using obscene language. In a way, I think, in Europe, there’s somehow more generosity towards the freaky artist, the drunken artist, the crazy artist. Here there’s a tendency for a person like that to be clean and straight and have a straight sense of business. You can fight with your lawyer, but you never hand out bad words to your producer. Nick just wasn’t that type — he was a man of discussions, of endless, riotous discussions.”

“Even in the good old days,” László Benedek said, “when he worked with Bogart [on Knock on Any Door and In a Lonely Place] and made regular, commercial Hollywood films, he had the reputation of being a difficult director — meaning he didn’t take orders willingly from the production department. But as long as these people made money, one could get away with that.”

“As much as Nick said that the artist has to expose himself,” Tom Farrell insisted, “he was deathly afraid of exposing himself. And when he realized afterwards that he had exposed a lot of himself, he tried to keep it from being seen. Without Wim, Lightning never would have been finished, because Nick would not have allowed it to be shown. It was another of those things — he had a block against showing his own work.”

Is that why he never finished We Can’t Go Home Again? Farrell thinks so. “Even when he talked about finishing during the course of that film, you could tell he was afraid to do it. Because for the first time, Wim actually offered to put up the money, to raise it — he had the resources. And for a while Nick was excited about that, about the possibility of finally finishing. And he had no excuse not to, for Wim offered that. But then he was afraid, he was withdrawing.”

A related interpretation of Ray’s character can be found in John Houseman’s Front and Center, the second volume of his memoirs. As someone who worked extensively with Ray in theater and radio, and produced two of his best early features, They Live by Night and On Dangerous Ground, Houseman has a sense of Ray’s origins that is more detailed than most:

From his year’s apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright, Nick had acquired a perfectionism and a sense of commitment to his work which were rare in the theater and even more rare in the film business. But in his personal life he was the victim of irresistible impulses that, finally, left his career and his personal relationships in ruins. Brought up in the Depression, one of a generation with a strong anti-Establishment bias, he had been taught to regard hardship and poverty as a virtue and wealth and power as evil. When success came to him in its sudden, overwhelming Hollywood way and he found himself, almost overnight, living among the rich and powerful with a six-figure income of his own, he was torn by deep feelings of guilt, for which his compulsive, idiotic gambling ($30,000 lost in one night in Las Vegas) might have been a neurotic form of atonement.

***

What about all of Ray’s unrealized film projects during his final years? There was an adaptation he wrote with Gore Vidal of a Dylan Thomas film scenario, “The Doctors and the Devils,” in 1965, not long after he opened a restaurant and nightclub in Madrid. The film was to be produced by Ray himself in Belgrade, with Warner Brothers providing part of the backing. But according to film historian Bernard Eisenschitz, who is researching a detailed biography of Ray [subsequently published in French in 1990 and in Tom Milne’s English translation in 1993], “The project fell through, apparently because the director walked out when the sets had already been built and Maximilian Schell had been signed for the leading role.” Among several European projects in the late Sixties was “In Between Time,” a thriller to star Terence Stamp that was prepared over the better part of a year with fledgling French producer Stéphane Tchalgadjieff (who went on to produce major works by Robert Bresson, Marguerite Duras, and Jacques Rivette, among others, including The Devil, Probably, India Song, Out 1, and Duelle).

“He was a great liar,” I was told by producer Chris Sievernich, who knew Ray only during the final months of his life. “He lied about everything one could lie about — it was a game somehow, I always felt. He just wanted to try out people. I think he conned a lot of people into money and projects and advances on projects. He traveled around, you know, and since he was Nick Ray, it was fairly easy to survive, I believe, within the European film community, where he was highly respected and regarded.”

Perhaps the most often discussed unrealized Ray project back in the United States were his film about American justice (which led him to Chicago to film the Conspiracy Trial and material relevant to the murder of Fred Hampton, where he met his future wife, Susan Schwartz) and “City Blues” (with Rip Torn and Marilyn Chambers) in the mid-seventies. Yet despite Ray’s intermittent work as an actor in The American Friend and Hair (where he played a U.S. army general), none of his countless plans for directing films ever took shape. Even after he joined Alcoholics Anonymous and stopped drinking in 1976, it was too late for his luck to change; as many have pointed out, he had simply burned too many bridges by then.

In Lightning Over Water, Ray in his Spring Street loft in Soho describes to Wenders the film he would like to make — the film that he initially hoped Lightning would be: “This is a film about a man who’s an artist, sixty years old. He’s made a lot of money in the art world on his early paintings. He’s not been able to sell his current output, and he has another great need, besides money, which is to regain his own identity as fully as he can before he dies. He is fatally ill with cancer and knows it. To regain his own paintings, he steals them, as well as forging his work and trying whenever possible to replace what he steals from museums with his forgeries. This is what he enjoys doing the most.”

“If you look into it analytically,” I was told by Benedek, who was present during part of the shooting of Lightning, “I think this idea for a film has something to do with all these fantasies he had about making films — at a point where he knew subconsciously that this was a fantasy.” According to Sievernich, “He lived on his projects. I think in a way he was very creative in developing and expanding ideas, but maybe he didn’t have the follow-through energy any more. It takes a lot, once you’re completely out of the grind. And I don’t think he was uncomfortable with his situation; I think he enjoyed tremendously being the rebel.”

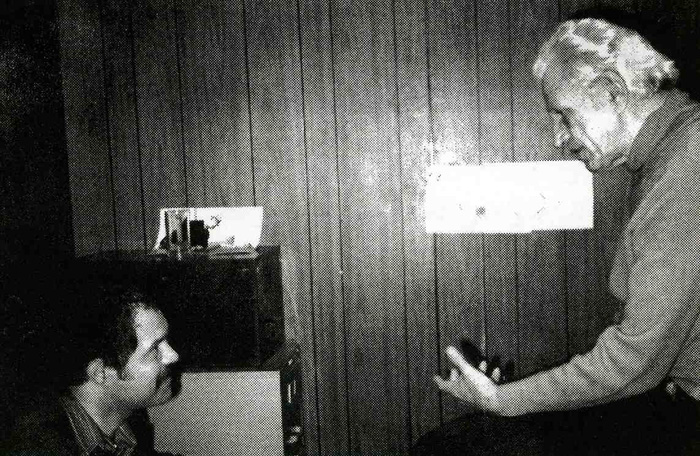

When Benedek invited Ray to teach a summer school directing workshop in 1977 — a course which Benedek himself had designed, which involved working with actors — a cautionary meeting was held with the two of them, the associate dean and the head of the undergraduate film school. “Not more than two minutes went by,” Benedek recounted, “when Nick said, ‘Gentlemen, I know exactly why you want to see me. So let me put my cards on the table. I’m not drinking. I’ve been to AA and I’m still going, so let’s just have this question out of the way.’ Of course, I was deeply moved by this, because I knew it wasn’t easy.”

After that summer, Ray was offered a more regular job at NYU teaching third-year film production students. By that time, he had already been operated on for lung cancer. “The trouble was, his health deteriorated much faster than he or we thought it would,” Benedek said. “It was difficult for him to keep the schedule of assigned hours. What helped a great deal was that three or four students really fell in love with him, picked him up at home, took him to school, and helped him physically in every way.”

“And what happened in class was that — I must tell you — he was absolutely brilliant,” Benedek said to me forcefully. “His function as a teacher was in a way limited by his physical weakness, and concentration for two hours was very difficult for him. But certain people profited a great deal, and were inspired by him — mostly the kind of students who didn’t keep asking, ‘What do you think will sell now in Hollywood?’ — nor the ones who thought they knew it all. The freedom and respect that he gave to actors was actually — I don’t want to be highfalutin’, but it was a spiritual teaching. Anyone who was willing to take that benefited a great deal from Nick.”

***

The last time I ever saw Nick in a social situation was the first encounter I had with him after our meeting ’73 in Paris. This was in late December 1977, less than half a block from his Soho loft. A mutual friend and I had just seen Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, and the friend proposed meeting Nick and another friend for dinner at the Spring Street Bar.

When Ray arrived at the restaurant with the other friend – the manager of a punk rock group who had once planned to publish a theoretical film journal called Bigger Than Life — I found the differences in his appearance and manner startling. In place of the gypsylike outfits he had favored in Paris, he was dressed in a conservative blue suit, wearing glasses instead of an eye patch, and his speech patterns were reasonably brisk and ordinary. He was full of enthusiasm for at least a couple of film projects, and most of the conversation remained light and inconsequential.

At one point, one of the friends reminded Nick of my having grown up in a Frank Lloyd Wright house. Some time later, with much encouragement on our parts, he proceeded to relate the story of his tempestuous falling out with Wright while studying with him in his early twenties — a rift that was apparently patched up to some extent afterwards.

It was a classic Nick Ray anecdote, full of macho hyperbole and braggadocio – yet another example of youthful rebellion against patriarchal authority. It involved a fairly modest architectural suggestion or question on Ray’s part that had provoked the full wrath and rage of the great man’s conceit. This curious thing about this tale now, as I try to remember it, is that the actual details of the encounter between Ray and Wright, which somehow involved manipulating architectural models, remain only shadowy sketches. What persists with extraordinary vividness is Ray’s performance of those details, using mainly his voice and his hands — a kind of expressionist mise en scène of temperaments and emotions, abrupt and staccato and full of his and Wright’s sound and fury, delivered with remarkable restraint and economy in a few bold gestures.

Only much later did it occur to me that, by finally fulfilling my initial request for a Wright anecdote, three and a half years later, Nick was at the same time exposing the vanity of my corny desire to hear one in the first place. What he gave me had nothing permanent about it, and that was both its poignancy and its power. With a few deft strokes, he had created an imaginary Nick Ray movie, as passionate as Johnny Guitar, that quickly vanished into empty space.