From The Soho News (October 27, 1981). — J.R.

It’s no surprise that My Dinner with André (loved by Vincent Canby), now on at the Lincoln Plaza, was one of the most popular films at the New York Film Festival — or that Lightning Over Water (hated by Canby), and now on at the Public, was one of the least popular. It isn’t just that the former movie says something that many of us want to hear, and says it well — nor that the latter says something that few of us want to hear, and says it problematically.

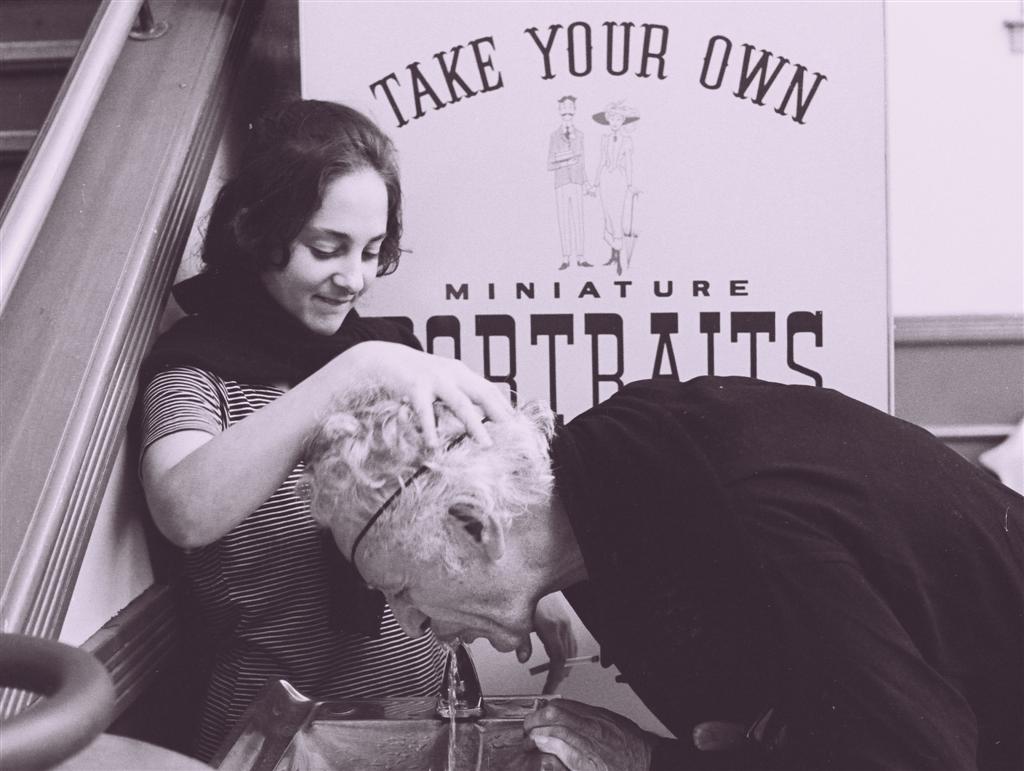

Each movie stars two artists who work in the world of make-believe, playing themselves, and yet the respective positions each pair takes in relation to playing this game couldn’t be more different. For André, director Louis Malle worked from a script by the two performers, playwright/actor Wallace Shawn and stage director André Gregory. For Lightning, film directors Wim Wenders and the dying Nicholas Ray almost concurrently wrote and directed their own performances, after a fashion.

Having once played myself in a film (Peter Bull’s The Two-Backed Beast, or The Critic Makes the Film), at the same time that I was writing a critical memoir that allowed me to play myself in a book (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies), I can well appreciate the subjective factors that enter into any exercise in self- representation. By the same token, I should expose my own slants on André and Lightning by acknowledging my personal links to each artist-performer. I’ve known Wally Shawn intermittently over a 22-year period, and he’s just about as nice as anyone can possibly be to someone he regards as a social inferior. I’ve met André Gregory once, recently, and then only because Wally asked to bring him along to our interview. I’d seen Nick Ray a few times during the last six years of his life, always as a social equal and acquaintance, never as a friend, and I’ve encountered Wim Wenders on similar amicable terms, most recently in connection with Lightning.

We all plays ourselves at times, which should qualify us to understand others doing the same thing on film. But it doesn’t. Too many offscreen facts intervene between us and these people to allow us to see any of them whole, so we settle all too easily into the first fictions about them that come our way. Often we don’t recognize that we’re selecting fiction over fact, or conflating the two into the kind of pseudo-truth that we usually expect from movies.

***

Whatever else one says about My Dinner with André, its technical achievement should not be denied. For the better part of 110 minutes, two friends meet at an expensive Manhattan restaurant and talk; longeurs are not entirely absent, but there aren’t many, and the naturalistic look of a real encounter is deftly maintained. Most of the talk comes from Gregory, recently back from mystical adventures in a Polish forest with an experimental theater workshop. He’s introduced in Shawn’s narration as a brilliant director who’d originally discovered Shawn’s plays, but who had since given up his career and mainly left his family to roam around the globe on various religious pursuits. Shawn listens in wonder, but eventually offers up some comic declarations of rational skepticism. Two seemingly dialectical worldviews are counterposed, and the men part as friends.

At the beginning of André, Shawn shuffles like a downtrodden near-derelict along a scruffy Soho street, complaining on the soundtrack about his life as a struggling, unproduced playwright: “I grew up on the Upper East Side, and when I was ten years old I was rich. I was an aristocrat, riding around in taxis, surrounded by comfort, and all I thought about was art and music.” After Shawn delivers the next line, the audience is squarely in his back pocket: “Now I’m 36, and all I think about is money.”

Most people who respond to this common-man earthiness aren’t aware that he’s the son of William Shawn, the editor of the New Yorker — a fact that has sometimes made me reflect that, given Wally’s social connections, it must be very difficult for him to evaluate his own work and career. My first information about André as a project came from one of his favorite playgrounds, the front page of the Sunday Times‘ Art and Leisure section, in an article about him and his father that was careful to work in tasteful fundraising pleas in the third paragraph and again toward the end.

“Louis encouraged us to treat the script as if we were two actors who received it in the mail,” Wally said at the festival press conference. “It doesn’t remind me of me.” Maybe not. But the movie reminds me of the New Yorker — the return of the repressed? — from beginning to end. Doesn’t Malle already have the same kind of economic/spiritual kinship with that magazine that Roger Vadim has to Playboy? Gregory’s “intimate” monologues about himself and the world are like long J.D. Salinger stories about the Glass family, complete with mystic parables, arch digressions, masochistic yet starstruck self-deprecations, and even toothless satire about the rich and spoiled. Shawn’s reaction-shot grimaces are like cartoons. The restaurant itself is a fair summary of the magazine’s ads, with the consumerist metaphor of the meal serving as a perfect corollary to “Goings On About Town” — the ponderously nonspecific chatter about The State of the Theater (“It can actually help people to come in contact with reality”) done in the anonymous style of any “Talk of the Town” item.

Something like a résumé for both its stars, André is a Hollywood art movie that doggedly flatters its audience, cozily inviting it to feel intelligent and concerned without thinking too much. “Whatever documentary aspect it may have,” Wally told me, “we wanted it to stand on its own feet as fiction. That, for instance, is different from Lightning, where obviously no attempt is made to create that illusion.”

Unlike the narcissistic self-hatred of Shawn’s play Marie and Bruce — which ends on a note of soppy uplift cribbed from the last pages of Ulysees and Franny and Zooey — André affirms something: friendship. Yet its equally conservative appeal invites identification, recognition, and confirmation, not discovery or reflection. No fewer than 40 people are listed in the credits for the realizing of this precious dialogue, shot in 16mm and blown up to 35.

***

“In the Wim Wenders movie,” Gregory told me, “which I admired enormously, “I felt that a problem was that the audience becomes separated in a way, and isolated by certain confusions.” “I’m never going to be finished with this movie,” Wenders was quoted as saying in the September 30 Variety. “Each time it’s shown, I still feel as if it needs the same kind of energy from me it needed when we were filming.”

People who denounce Wenders for exploiting Ray in Lightning don’t seem to realize that if the film hadn’t been made, Ray would have probably wound up dying in a charity ward. (He was virtually broke, having burned a lot of bridges behind him, and the production immediately took over his expenses.) “I did my part to help Nick a lot,” Tom Luddy told me about Ray’s last years, “and so did many others. But nobody did what Wim did, which was to really allow him some decency.”

Los Angeles critic Myron Meisel described Lightning to me as “an act of witness for Nick’s sake. It was made to be made, not made to be seen.” I would describe the first, [then] unreleased version of Lightning edited by Peter Przygodda [now known as Nick’s Movie and available in Europe] — which showed publicly at Cannes and Venice in 1980, before Wenders withdrew it and re-edited it into the present version — as an act of witness for the truth’s sake, however indigestible the truth of that tense, grim shooting might have been for the people involved. As it stands now, the film is an unholy jumble of things, some of them moving, some appalling, some in between the two (like Ray and Wenders playing themselves badly), some naive, some protective shields (like Wenders’ brittle film noir narration, which wasn’t in the first version) — all united, perhaps, by the disturbing yet revealing phenomena of what happens to certain people when you place a camera in front of them.

The fact that Lightning begins with a self-conscious, artificial restaging of something that really happened (Wenders arriving by cab in Soho to make a film with Ray), while Shawn’s convincing schlep and subway ride across town to meet Gregory for dinner is a fabrication, only begins to describe the different codes of etiquette that apply. The same goes for privileged information. Of the five participants and three observers on Lightning that I’ve spoken to, not one has ever told me anything in confidence, or intimated that there were any “inside” stories to dig for, despite all the real traumas that the shooting occasioned. But Shawn was divulging production secrets to me even before our interview started, indicating that he wanted to keep the real location of the restaurant a mystery. Big deal. [2011 footnote: It was in Richmond, Virginia, where I’m currently retyping this article.] If, as he puts it in the movie, all he thinks about is money, maybe that’s the major difference.

What do we need to know in order to make sense of Lightning, either as a work (modernist scrapbook documentary) or as a deed (act of witness)? It helps if you know that 16 years have passed since Ray collapsed on the set of his last Hollywood feature, and he has not even brought his one surviving independent/maverick production, We Can’t Go Home Again, to completion; also that, after a lifetime of alcoholism, Ray joined AA and quit drinking in the late 70s, only to find that he still couldn’t finance a production of his own, and had terminal brain cancer besides. At this point, Wenders was able to mobilize enough money for a low-budget West German/Swedish coproduction.

When people say that Lightning was monstrously misconceived, it’s hard for me to know what they mean. Are they saying that Ray should have had the good taste to die without even trying to justify his last 16 years — or that Wenders should have had the good taste to prevent him from trying? Or are they implying, rather, that Ray had a perfect right to make a movie about facing death, and to ask us to face it in turn — as long as he made it entertaining, like André, with the right box office values?

As a feminist friend points out, playing with oneself is the subject of both movies, an activity from which ladies are basically excluded. According to Canby, the only people in Lightning who “come off sympathetically” are the directors’ spouses, Ronee Blakely and Susan Ray. I agree that the failure of both versions of Lightning to deal with Susan’s relation to Nick, whether willed or not, is almost total, and a serious flaw. But when I reflect on all the resentment I’ve heard from people who worked on the film about the star-turns imposed by Blakely, on a project that she was initially related to only because of her marriage to Wenders (now a thing of the past), I can’t feel quite so indulgent as Canby, who describes her “gamely” attempting “to improvise a most peculiar sketch with Mr. Ray,” when it appears that the game was chiefly hers.

Both Lightning and André are available in book form, although only the latter (Grove Press, $4.95) is represented in its original and longer version. The former, published by Zweitausendeins for $15, is to my mind worth far more than that. Coproducer Chris Sievernich rightly speculates that Lightning may work better as a book than as a film — not only because the dialogue is easier to grasp and absorb that way, but also because the more casual eye of a reader makes the subject matter somewhat less relentless and more subject to reflection.

André, by contrast, has less to offer in book form, intellectually or aesthetically. Without the charismatic direction or performances to give the words life, they lie flat on the page, the issues never advancing very far beyond those of a high school debate — blocked as they are by unending torrents of self-ingratiation.

“Suppose you’re going through some kind of hell in your own life,” Shawn muses, “well, you would love to know if your friends have experienced similar things. But we really don’t dare to ask each other.”

“No,” says Gregory. “It would be like asking your friend to drop his role.”

It’s a conversation that could only take place between show-biz types. In any case, no one in André is ever asked to drop his role — not even the spectator.