From the Chicago Reader (November 29, 2002). Soberbergh’s Contagion confirms his bottomless cynicism, as well as the cynicism of those reviewers who seem to like him because he expresses their jaundiced views. I continue to find that same cynicism lethally dull and all too familiar. — J.R.

SOLARIS

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Steven Soderbergh

With George Clooney, Natascha McElhone, Viola Davis, Jeremy Davies, and Ulrich Tukur.

It’s easy to scoff at Monarch Notes, but before I quit graduate school in disgust I reached for them every time I thought a professor might be ruining a literary masterpiece for me — and vowed to read the work later, on my own time, for my own reasons. As a teacher, I also used them when I suspected a student of plagiarism, and they did help me spot an offender or two. But having read the outlines, I rarely read the works — the crib had robbed me of the desire.

If you haven’t seen Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 SF masterpiece Solaris, can’t see it Friday night, November 29, on Turner Movie Classics, and don’t want to watch the just-released DVD or wait for the Music Box’s rerelease in January, you might find Steven Soderbergh’s remake intriguing and compelling, because the story it tells is certainly haunting. If you have seen the Tarkovsky movie and couldn’t make heads or tails of it, Soderbergh’s synopsis could iron out most of the confusion, though it leaves you with little but the bare bones of the story — until the end, when it decides to get fancy and offer three enigmatic conclusions instead of Tarkovsky’s one.

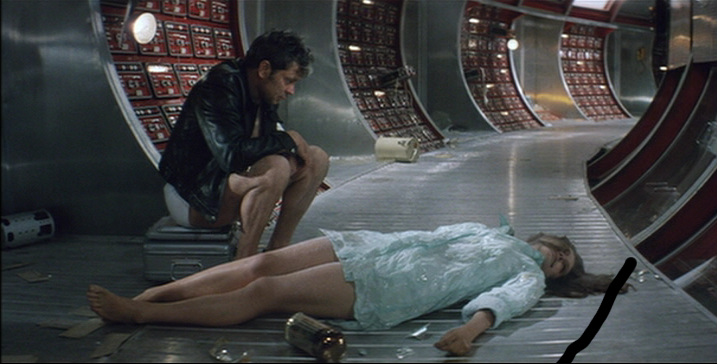

It’s also true that SF art movies — which offer a thoughtful alternative to the usual action-packed SF romps — don’t come along every day, though back in the 60s and early 70s filmmakers as diverse as John Boorman, Jean-Luc Godard, Stanley Kubrick, Joseph Losey, George Lucas, Tarkovsky, and Francois Truffaut all tried their hands at them. Moreover, Soderbergh’s film is deliberately constructed like a dream, with its own peculiar logic and funereal tone — though he hasn’t bothered to ground it enough in everyday life on earth to make the trip into outer space feel like much of a departure. He seems glued to a mood; his notion of reality consists mainly of dank urban rain and gloomy interiors out of Blade Runner, and his sense of outer space is strictly 2001. He starts cribbing from Tarkovsky in earnest only when he gets to the space station that’s the film’s main location.

The problem is, whichever version of Solaris you encounter first may well spoil the other — as well as the book. I saw the Tarkovsky film before I read the 1961 Stanislaw Lem novel it’s based on, which suffered a lot as a consequence. Soderbergh’s Monarch Notes job is several rungs below both. And it doesn’t even cite its key source, Tarkovsky’s film, in the credits. So if you get to it first you’ll probably be cheating yourself; I’d call it “worth seeing” only if you’ve already seen the Tarkovsky.

Soderbergh has one theoretical advantage over Lem and Tarkovsky — terseness — and viewers can have a bit of fun watching him try to squeeze the essence out of Tarkovsky’s meditative poetry. Soderbergh’s film lasts only 99 minutes — 90 minutes less than Tarkovsky’s and much less than it would take to read Lem’s 200-page novel. In Tarkovsky’s film more than 40 minutes elapse before Kris Kelvin, the hero, takes off into outer space to investigate and possibly rescue the scientists on a space station circling the planet Solaris. Soderbergh’s Kelvin arrives there before we’ve even had a chance to get acquainted with him. Just about all we know is that he’s a troubled shrink (no longer a psychologist) who lives alone, but since this time he’s George Clooney — working up a photogenic sweat at every opportunity and going off the deep end before he’s shown us whether he’s playing a good shrink or a lousy one — I guess we aren’t supposed to care.

The scientists mysteriously broke off all communication with earth some time earlier; Kelvin has been summoned by a cryptic video transmitted by the commander, an old friend named Gibarian (Ulrich Tukur), suggesting that Kelvin’s the only person who can save them. (The video is delivered to Kelvin’s kitchen by a couple of “suited professionals,” as they’re identified in the credits — presumably executives from the private company we eventually discover NASA sold the space project to, though Soderbergh inexplicably makes them look like hoods.) Once he arrives, Kelvin discovers that two of the scientists, including Gibarian, are dead; one is missing; and the other two — a confused young stumblebum named Snow (Jeremy Davies) and a relatively focused black woman named Dr. Gordon (Viola Davis, a PC replacement for a white male in the original) — are in solitary confinement, each wrestling with an unseen personal demon.

Once Kelvin goes to sleep, he’s visited by a personal demon of his own — his late wife, Rheya (Natascha McElhone), whose suicide he feels responsible for. As it turns out, she’s a projection of his memories of her, though she has a somewhat independent will, and the remainder of the story, once he realizes that she’s neither human nor emotionally expendable, basically consists of his tortured struggle with all that she represents. (We only faintly discern Snow’s projected demon, his brother, and the fact that we learn nothing at all about Gordon’s is perhaps the film’s most original and provocative gesture; in Tarkovsky’s version, both demons are barely glimpsed.)

Soderbergh has correctly noted that his biggest departure from the two previous versions lies in the detailed flashbacks about the relationship between Kelvin and Rheya on earth. Unfortunately most of this is closer to a Hollywood wet dream than an encounter between people, and the perverse result is that Rheya’s pieced-together replica is much closer to a character. Yet even here McElhone is severely limited by Soderbergh’s insistence on directing and framing her like a poster girl. (The replica of Rheya also commits suicide, then jerks back to life in an eerie resurrection, which Soderbergh handles more like a special effect than a performance — a stark contrast with Natalya Bondarchuk’s truly remarkable enactment of that process in Tarkovsky’s film, one of the rare moments when he allowed an actress to shine.) Admittedly, all three versions of Solaris include a highly subjective first-person narrative, yet we can’t even start to carve out an objective basis for the fantasy projection in Soderbergh’s version because false Hollywood details keep creeping in from every side — demons of another kind. (If it isn’t Clooney’s bare ass or his glistening sweat, it’s the tear rolling strategically down his nose — all of which seem part of an Oscar bid.)

The story’s too strong for Soderbergh to kill — though he comes close. He tends to place most of the psychological and philosophical material in italics rather than trust an audience’s intelligence, and he creates an overall sense of brusqueness — even Gibarian’s video speech encapsulating the story’s main theme is reduced to a sound bite (”We don’t want other worlds. We want mirrors”) and stuck in the background of a transitional shot. But then Soderbergh has asked the four leads to carry the whole show, letting the two guys “act” up a storm and the two ladies pose (though, as I mentioned above, these activities are often made to seem interchangeable).

By contrast, Tarkovsky gets some of his loveliest and most memorable moments from such everyday details as the tremulous swaying of underwater leaves and the endless rush of an anonymous urban freeway — both poetically shaped to suggest drifting through outer space. The nearest Soderbergh comes to trying for such an effect are close-ups of raindrops hitting a window that are used to frame the action, yet he can’t resist lighting and directing the raindrops as if they were little George Clooneys or little beads of sweat on George Clooney. Several months ago Clooney suggested in an interview that people shouldn’t worry about Soderbergh ruining a classic because Solaris wasn’t one of Tarkovsky’s better pictures. I assume all these vivid splats of moisture are his idea of an improvement.

Published on 16 Sep 2011 in Featured Texts, Featured Texts, by jrosenbaum