From the Chicago Reader (September 16, 1988). — J.R.

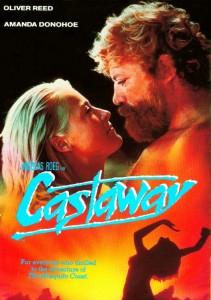

CASTAWAY

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Allan Scott

With Oliver Reed and Amanda Donohue.

ASSAULT OF THE KILLER BIMBOS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Anita Rosenberg

Written by Ted Nicoleau, Rosenberg, and Patti Astor

With Christina Whitaker, Elizabeth Kaitan, Tammara Souza, Mike Muscat, Nick Cassavetes, Dave Marsh, and Patti Astor.

A RETURN TO SALEM’S LOT

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Larry Cohen

Written by Cohen and James Dixon

With Michael Moriarty, Samuel Fuller, Andrew Duggan , Ricky Addison Reed, June Havoc, Evelyn Keyes, and Ronee Blakley.

The three movies listed above are all probably playing in Chicago this week, but not in any local theaters; they’re available in video rental stores and playing on home screens. Recent releases that have never opened theatrically, and presumably never will, they represent a growing breed of movie, at once omnipresent and unacknowledged.

Ever since the fairly recent time when the amount of money spent in this country on video rentals began to exceed the amount spent on movie tickets, notions about moviegoing have become even more specialized and limited. In contrast to moviegoing in the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s, when individual movies provided national experiences that were public and shared, moviegoing in the 60s, 70s, and 80s has increasingly become a less communal activity. The audience itself first subdivided in the 50s, when teen culture pulled away from the “general audience” mainstream and developed a separate market of its own; then the studios produced further cultural divisions by systematically targeting separate audiences and interest groups; and finally the advent of movies on tape has taken them from a public forum and placed them firmly in the private sector.

Thanks largely to this change, two separate movie cultures have taken shape. Most of the space in the media accorded to movie reviews is commanded by the old movie culture of theatrical releases. The new movies-on-tape culture is dealt with more sporadically and haphazardly–rather the way theatrical movies were handled in the press in the teens and 20s. Outside of a few video magazines and trade journals, new movies like Castaway, Assault of the Killer Bimbos, and A Return to Salem’s Lot, which are released in the U.S. almost exclusively on tape, get no attention at all. Unlike the media blitzes that accompany movies greased by expensive publicity machines, the media blackouts accompanying only-on-video releases are welcome in a way: video audiences are freer to follow their own whims, without critical and promotional prodding, and those with a spirit of adventure can make discoveries on their own.

In other respects, though, the silence of the press about these releases warps and limits our sense of movies as a whole. Just because a film fails to get a theatrical release, there is no reason to assume that it is any less important, less interesting, or less entertaining than the ones that hit the theaters. (Movie marketing strategy is often regarded as a science, when in fact it’s usually closer to astrology or roulette.) In fact, all three of the movies reviewed here are better than the average run of theater releases that I’ve seen over the past few months. They’re all less boring than Eight Men Out, less sentimental than Stealing Home, less empty than A Summer Story or Young Guns, less pretentious than A Handful of Dust, and less stupid than Cocktail or Arthur 2: On the Rocks.

Castaway, based on a nonfiction book by Lucy Irvine, follows a man and a woman who voluntarily spend a year together on a desert island. The man, Gerald (Oliver Reed), places a classified ad in the London listings weekly Time Out; we see him drafting it in the opening shot, behind the credits: “One year on a desert island. ‘Wife’ 20-30 needed to accompany man 45.” (Gerald crosses out “45″ and replaces it with “35+,” which already clues us in to some of the problems he will have to face later.)

The film’s opening adroitly charts, with intercutting, the separate lives of Gerald, a publisher, and Lucy Irvine (Amanda Donohue), an Inland Revenue clerk; Gerald is seen in a pub and with his young sons at home, Lucy on her way to work and with her female flatmate in their cramped apartment. Glimpsed newspaper headlines and overheard TV news stories hint at a general disturbance in traditional sexual roles, and when Lucy finally phones Gerald in response to his ad, both have TVs tuned in to the same movie about marital discord (The Pumpkin Eater); to enhance the rhyme effect, after the call both Lucy and Gerald report that they’ve been speaking to a friend.

In spite of a marked difference in their ages and attitudes (Gerald awkwardly informs Lucy at their first meeting, “You’re definitely going to be on my shortlist,” and generally comes on like an old-style chauvinist), the two hit it off, sleep together, and make preparations for traveling to Tuin, an island off the northern coast of Australia. They encounter their first serious problem when they learn that immigration laws require them to get married first; Lucy isn’t happy with this, since it effectively removes the quotation marks around “wife” in Gerald’s ad, but she reluctantly complies. A female journalist accompanies them to their tropical paradise, but soon they’re left alone — at which point the real trouble begins.

A pivotal point of contention is Lucy’s refusal to have sex with Gerald again (although she goes around seminude or nude for most of the film). Her reasons are never fully spelled out, although it’s evident that her irritation about Gerald’s laziness in building a shelter and his reluctance to lead a more structured life on the island has something to do with it. Gerald spends much of his time reciting obscene limericks, mainly to himself, and reading self-improvement books, although he does plant a vegetable garden and teach Lucy how to fish. Despite Lucy’s refusal to put out, she treats Gerald with consideration in most other respects; when he is badly stung by bees, for instance, she conscientiously nurses him back to health. A day’s visit from a couple of young men who are census takers unleashes some of Gerald’s rage and sexual frustration, but otherwise nothing essential changes between him and Lucy. Eventually they both become seriously ill, and nuns from Badu, a neighboring inhabited island, rescue them; afterward, Gerald takes periodic trips from Tuin to Badu to help the local populace as an all-around mechanic and also, apparently, to satisfy his sexual appetites. His increasing absences finally goad Lucy into sleeping with him again (and, more than that, into turning herself into a sex object a la Playboy in order to seduce him). After more than a year on Tuin, Lucy returns to London and Gerald decides to remain with the islanders on Badu.

The fact that all of this is based on a true story gives the film an air of uncertainty: one is never clear how much of the story is being invented or extrapolated from actual events. But Roeg is clearly nonjudgmental in the way he treats each character, and the ambiguities and densities of a real relationship are suggested throughout. (One even suspects that the factual basis of the story, as in Bresson’s A Man Escaped and Scorsese’s Raging Bull, adds to the sense of mystery rather than detracting from it, because the filmmaker respects the material too much to grossly “interpret” it.) Though the overall treatment is realistic, there are certain scenes that aren’t clearly real or imagined — and if they’re imagined, one can’t be certain whether it is Lucy or Gerald who is imagining them. Most of the scenes are brief, and they typically end inconclusively, with quick fade-outs; Roeg often cuts away to underwater shots to punctuate the dialogue (the film is resplendent with water imagery, majestically shot by Harvey Harrison), as if to suggest that the unspoken and unseen undercurrents between the couple are every bit as important as what we see and hear.

Castaway is the first Roeg movie since Don’t Look Now (1973) that’s scripted by Allan Scott, and the first Roeg movie since The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) that doesn’t feature his wife Theresa Russell. It is his second feature to be denied an American theatrical release (after the 1981 Eureka), and it already seems possible that his latest film, Track 29 — which was originally slated to open theatrically this summer, but has been repeatedly held back — won’t open in Chicago theaters either. [Postscript: It did.] Yet there are few contemporary English-speaking filmmakers around who are as consistently serious, adventurous, and interesting as Roeg is even when he fails (which is often), and few with a sense of style and form as well-defined as his. In some respects, his quasi-maverick status recalls that of John Boorman, at least before Boorman became respectable with Hope and Glory.

Oddly enough, the prototypical Roeg film, and in some ways the best, predates his directorial career: Petulia (1968), which was signed by Richard Lester. Roeg was Petulia’s cinematographer, and it seems likely that he found the basis for his own fast-cutting style and mosaic form in that picture, which retrospectively seems to fit very snugly within his oeuvre.

Castaway, to my mind, qualifies as one of his better recent works — a film that explores the mysteries of a contemporary relationship and actually manages to make a virtue of its detachment and open-endedness. The performances of Reed and Donohue are both richly detailed, and the film’s adept handling of the passage of time and the subtle developments in both characters keep it absorbing — which is no small achievement considering the overall absence of a clear “dramatic” agenda.

No such claims can be made for the likable but modest Assault of the Killer Bimbos, a first feature and low-budget exploitation item whose chief virtues are its unflagging cheerfulness and its unpretentious efforts to express some semifeminist attitudes in a genre of filmmaking where they’re hardly expected. The action centers on a waitress named Lulu (Elizabeth Kaitan) at the Aladdin-a-GoGo in Los Angeles. When one of the go-go dancers fails to show up, Lulu offers to fill in, but her act proves to be a disaster. The artificial fruit decorating her bikini flies off and hits various customers, and her general lack of expertise elicits jeers from the sleazy clientele. Shifty Joe Malone (Dave Marsh), the emcee and boss, calls her a bimbo and fires her on the spot. When Peaches, the main dancer, objects to this epithet, she and Lulu are both given their walking papers. As they’re preparing to leave, Shifty Joe is shot in his office by a hit man named Big Vinnie (Mike Muscat), who hands his gun to Lulu before he splits.

Needless to say, because Lulu is seen with the gun, she and Peaches become the prime murder suspects, and they immediately set out for Mexico in Peaches’s convertible. (”From now on, it’s us against the world!”) Dogged by radio descriptions of them, they stop to change clothes before entering a roadside cafe, where Lulu’s hot pants cause a commotion. There they meet a trio of beach bums (including Wayne-O, played by Nick Cassavetes, whom Lulu falls for) and befriend the beleaguered waitress Darlene (Tammara Souza). When a cop enters and tries to arrest them, Peaches holds her own gun to Darlene’s head and the three women take off in the car. It turns out that Darlene welcomes the excuse to leave her boring job, and after a few more chases and other adventures, the “killer bimbos,” the surfers, Big Vinnie and his girlfriend Poodles (Patti Astor), and the cop all miraculously converge at the same sleazy “no-tell” motel in Jalapeno, Mexico.

Part of my affection for this little movie is its revival of the kind of good-natured, semimindless romp that was much more common in the 60s and 70s, usually on the bottom half of double-bills at drive-ins. Flavored with peppy lines (like Peaches’s “Eat lead, bozos!” and Lulu’s “Put the pedal to the metal!”), Assault of the Killer Bimbos breezes along on its celebration of female camaraderie and everyday concerns (there’s a great deal of discussion, for instance, about whether or not “good-looking babes” need to wear makeup), usually to the churning accompaniment of pop songs on the sound track. (The featured single is “Don’t Call Me Bimbo.”) Undeterred by its lack of a theatrical release, the video includes a breathless promo for such spin-off items as a sweatshirt, a sound-track album, and a poster (”Join the Bimbomania . . .”), and even a sequel is threatened: “Bimbo Barbeque . . . the sizzling saga continues.”

A Return to Salem’s Lot, another exploitation picture, is a good deal more ambitious, albeit a bit choppier as well, with bargain-basement special effects and a rather shaky plot. Director and cowriter Larry Cohen is widely regarded as one of the unsung heroes of low-budget genre filmmaking — there’s a useful critical survey of his prolific output by Robin Wood in his book Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan — but for reasons that elude me, not many of his efforts seem to have made it onto video. I admired Cohen’s script for last year’s Best Seller, and was intrigued by his 1977 The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover, but otherwise my acquaintance with his work is cursory at best. His present effort is a sequel to Salem’s Lot — a 200-minute made-for-TV opus, based on a Stephen King novel and directed by Tobe Hooper — which I haven’t seen. (According to Leonard Maltin, the overseas theatrical version of the Hooper film, 88 minutes shorter yet more violent, is available on tape here and turns up on cable as Salem’s Lot: The Movie.)

Joe Weber (Michael Moriarty), an anthropologist labeled by one of his cohorts as “a cold-blooded son of a bitch,” is called away from fieldwork in South America by his ex-wife (Ronee Blakley) in order to assume custody of his teenage son Jeremy (Ricky Addison Reed), a rebellious problem child. Joe drives with Jeremy to a broken-down bungalow in Salem’s Lot, Maine, willed to him by his Aunt Clara, whom he visited as a child.

It doesn’t take Joe and Jeremy very long to discover that Salem’s Lot, formerly known as Jerusalem’s Lot, is a village of vampires who originally settled there as pilgrims in the early 17th century, Joe’s Aunt Clara (June Havoc) among them. During the day, while the vampires sleep in their coffins, the town is run by human drones with no apparent will of their own. The leaders of the vampire community, Judge Axel (Andrew Duggan) and his wife (Evelyn Keyes), want Joe to use his ethnographic skills to write a “true” chronicle of their community — a “history” and “bible” that will become public in another 200 years, when the general public is ready for it. Although Joe is understandably reluctant to go along with this, he is eventually persuaded to embark on the project both by his son Jeremy (who likes the place and takes a shine to a young female vampire) and by his childhood sweetheart Cathy (who, like the other vampires, hasn’t aged and who seduces Joe and becomes pregnant by him).

If the above sounds a little cockeyed, the film becomes even screwier as it develops, and it suffers as well as benefits from this overall flakiness. Many of the background details are either fudged or kept blurry–perhaps an acquaintance with Salem’s Lot would help to straighten some of them out — and the script abounds in continuity problems. But the apple-pie Americanism and the alleged purity and Republican-like rectitude of the vampires makes for some effectively grisly satire. “We’re all dairy farmers in these parts,” Judge Axel points out to Joe while taking him on a tour of a barn, coming on rather like Ralph Bellamy in Rosemary’s Baby with his homespun folksiness. “You outsiders grow stock for meat, we grow ‘em for blood. See, human blood is still the best, but the way things are going nowadays, it’s not quite good for you, what with drugs and alcohol, hepatitis, and this AIDS virus going around.” Meanwhile, hapless human passersby are being sucked dry by the local populace, but Axel argues that the vampires subsist mainly on blood from the cattle.

What originally attracted me to A Return to Salem’s Lot, and what turns out to be its most winning feature, is the presence of filmmaker Samuel Fuller. He plays a human character, a compulsive Nazi-hunter and -killer named Van Meer who turns up belatedly but subsequently dominates the film and its remaining action. One of the surviving giants of Hollywood filmmaking, still working in his late 70s as a writer-director and novelist in Europe, Fuller has been appearing as a highly charismatic character actor in films by Jean-Luc Godard, Dennis Hopper, Steven Spielberg, Wim Wenders, and others since the 60s, and this low-budget effort provides him with his most extensive role to date. One of Fuller’s most distinctive traits as an actor is that he never memorizes lines; seeing himself mainly as a script doctor, he locates what he considers to be the “holes” in a script, in collaboration with the filmmaker, and then improvises a performance (or, in some cases, a cameo) designed to fill the holes.

In the case of A Return to Salem’s Lot, the holes that Fuller fills make up the narrative drive of the whole latter portion of the movie and provide a welcome gust of reality as well. Van Meer drives into Salem’s Lot looking for a former Nazi, but he quickly takes over the faltering Joe’s role as a moral and patriarchal force — teaching Joe how to discipline his son and leading him on a mission to destroy the vampires, which for him are the equivalents of Nazis. Fuller charges through this patchwork movie — a jumble of intriguing but disconnected and unstructured notions — like a crusader. If he doesn’t quite plug up all the gaps in the continuity, he does give the whole movie a shape and direction that it badly needs.

Published on 30 Aug 2011 in Featured Texts, Featured Texts, by jrosenbaum