From the Chicago Reader (May 24, 1991). What prompted me to repost my thoughts about Andrew Dice Clay in 2017 was, oddly enough, the Summer issue of the French quarterly magazine Trafic, which arrived in yesterday’s mail and where the lead article, about our Madman-in-Chief, cites J. Hoberman’s excellent analysis of Trump, which alludes pertinently to Clay. — J.R.

TRUTH OR DARE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Alek Keshishian

With Madonna.

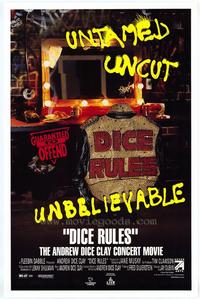

DICE RULES

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Jay Dubin

Written by Andrew Dice Clay and Lenny Shulman

With Andrew Dice Clay.

“I know I’m not the best singer or the best dancer. I’m interested in pushing other people’s buttons.”

— Madonna in Truth or Dare

“I have no tolerance for anyone or anybody.”

— Andrew Dice Clay in Dice Rules

Madonna’s Truth or Dare and Andrew Dice Clay’s Dice Rules are performance films about sex and defying taboos that are clearly conceived as statements from and about their stars. The movies are radically different, but they have a few things in common: an adolescent sense of outrage spurred by adolescent fans and energies, a postmodernist reliance on movie-star models, a preoccupation with narcissism and masturbation, and a painstaking effort on the part of their stars to “explain” themselves.

Truth or Dare, which comes on as if it were truth and dare, sets out to give us both the “real” offstage Madonna, shot in grainy black and white, and the performing Madonna during her “Blond Ambition” tour, shot in color. But our sense of documentary reality is limited in a number of ways: by offscreen past-tense narration from Madonna identifying and contextualizing what we see, by jazzy crosscutting between color and black and white that prevents us from fully taking in either (occasionally the film breaks its own rules by offering brief offstage segments in color), and by Madonna’s relentless determination to theatricalize her life — or at least those parts that are lived in front of cameras.

By contrast, Dice Rules opens and closes with two blatant fictions. The first is an awkwardly staged narrative segment called “A Day in the Life,” scripted by Lenny Schulman from a story by Clay and starring Clay — “Dice,” as he’s known — who is the reverse of Clay’s stage persona. As the more familiar Clay explains to us in interpolated shots, this story is meant to show us how he got to be the way he is. Dice is a fumbling, hapless, infantile nerd, a cross between Jerry Lewis’s idiot persona and Pinky Lee, tyrannized and beaten by his monstrously obese and vicious wife (a John Waters gargoyle), and gratuitously and sadistically persecuted by everyone he encounters — a bank teller, an older Jewish friend he runs into on the street, a couple of grocery clerks (one of them Indian), a black filling-station attendant, and a fat doctor. Then he sees a leather jacket in a window display inviting him to “Be a Real Man,” and is persuaded by a store salesman (also played by Clay) that “Leather makes it happen.” (Specific allusions are made to Marlon Brando and James Dean.) When he comes home leather-jacketed and smoking a cigarette, he’s a changed man, capable of ordering his wife around, insulting her, and rendering her awed and breathless after a long, passionate kiss. (It’s a bit like one of those Charles Atlas “I was a 99-pound weakling” ads, except that at the end the hero winds up not with a curvy blond but with the same monstrous wife.)

The remainder of the film consists of Clay’s performance for 20,000 spectators at Madison Square Garden, and the second fiction is the conclusion of that performance: Clay singing a song in which he imitates Elvis and doing comic impersonations — some adroit, some not so good — of Sylvester Stallone, Robert De Niro, Eric Roberts, Al Pacino, and John Travolta that record their responses to various animals at a zoo.

There’s another, much more subjective contrast between the Madonna and Clay movies. Even though I regard Truth or Dare as something of a con game — neither truth nor dare in any rigorous sense, but a skillful promo — I was charmed, entertained, and won over by most of it. But even though I regard Dice Rules as grotesquely straightforward about its own agenda, I found it horrifying, saddening, and ultimately sickening — though by no means uninteresting.

Broadly speaking, one might say that Madonna’s message boils down to a complex truce between love and narcissism, while Clay’s message boils down to a compound of hate and a form of narcissism that often seems indistinguishable from self-loathing. Madonna exalts and celebrates sex, identifying it with pleasure; Clay simultaneously brandishes and trashes sex, equating it with both bravado and disgust. Both performers seem unusually preoccupied with “attitude” and striking poses, and both clearly see part of their role as challenging the censors.

Madonna purports to be presenting her true self, warts and all — Madonna Louis Ciccone, who hails from a middle-class Catholic family in Detroit. Though her R-rated movie can be credited with a certain amount of candor, it’s important to bear in mind that she financed it herself and it is fully under her control. Clay, by contrast, has often insisted that the persona he presents onstage — and presents here, in a NC-17 movie — is not his true self but a fabrication; assuming that this is accurate, we have no access at all to the real Andrew Clay Silverstein, who hails from a working-class Jewish family in Brooklyn. What we get instead is “A Day in the Life,” which, apart from being the clumsiest piece of filmmaking I’ve seen this year, is striking mainly for its utter lack of believable social reality. The only allusion to his ethnic background is the Yiddish that punctuates the rap of his older Jewish friend and the urban setting, which loosely resembles Brooklyn. But the behavior that everyone exhibits, while it may illustrate some vague emotional principle, makes Jerry Lewis look like a naturalist.

Lewis, I should add, is crucial not only as a model for Clay’s nerd persona. Lewis’s Buddy Love, the vain greaser he plays in The Nutty Professor, is the principal (if unacknowledged) model for Clay’s onstage persona — leather jacket, cigarette, jewelry, manelike black hair, and all. Clay actually mentions Lewis at one point in his public performance, but pointedly not as a role model (unlike the eight non-Jewish stars he cites or imitates). Significantly, he claims that “Chicks when they have an orgasm sound like Jerry Lewis.” It’s a classic instance of the return of the repressed, because I think one can argue that it is Clay’s fear of his own femininity — or at least what he consciously or unconsciously perceives or misperceives as his own femininity — that forms the basis for his act. It’s a fear that might be said to come in two forms: fear of the ineffectual and passive Dice, who is obviously important enough to warrant a whole awkward section of this movie; and fear of the bossy, narcissistic, glamorous, and strutting Clay, whose preoccupation with his own image as a sexual object puts him within hailing distance of Madonna.

***

One of the hallmarks of pop postmodernism is a plundering of the past that nonetheless persuades the audience it’s watching something brand-new. This is more or less what Truth or Dare does. Many reviewers have noted that the overall look and form of the movie owe a lot to Don’t Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker’s 1967 documentary about Bob Dylan’s 1965 concert tour of England. Then there’s Madonna’s use of Marilyn Monroe as a role model, principally in her offstage manner, attire, and makeup. It’s a reductive use, paring away the multiple and contradictory levels of Monroe’s best performances (like her character’s simultaneous stupidity and guile in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), settling on the softness and vulnerability that were always the most obvious parts of the Monroe persona and which serve here mainly to counterbalance the opposite traits in Madonna’s personality.

Many of the highlights of the movie are being heralded as if nothing remotely like them has ever been seen on the screen before. This is patent nonsense, though given the enforced amnesia brought about by the media conveyor belt that passes along every “unique” product (each designed to supplant and abolish its predecessors), it’s a routine and understandable kind of nonsense. Two gay men passionately French-kissing? Check out Jack Hazan’s beautiful and long-neglected A Bigger Splash (1974), an English documentary with fictional interludes about the painter David Hockney. Madonna using a bottle of mineral water to show how she gives head? Take a look at what Jane Fonda does with a saxophone mouthpiece in Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown (1967), which happens to be playing in Chicago this week. Still, I can’t recall another movie whose heroine recites an “Ode to Farting,” so credit Madonna with a first in that department.

To my surprise, I found myself enjoying the offstage Madonna much more than the concert Madonna, largely because the material is much fresher. The numbers onstage suffer from being twice dismantled and reassembled: music videos that are “re-created” on the stage are splintered again by director Alek Keshishian’s music-video strategies; the effect is not to bring them back to square one but to serve up a third-generation spin-off. Intercutting this footage with the black-and-white documentary footage only further fragments whatever dramatic continuity the original number had. (A fancy cutter in the MTV mold, Keshishian manages his best effect in a backstage segment, when he cuts from a movement of Madonna’s masseuse to a crack of thunder outside.) Most of what we see onstage and off is about sex, but it’s debatable how sexy the numbers themselves are. The sweaty gymnastics and struck poses are more cerebral than suggestive on any visceral level; it’s the idea of stardom as orgasm more than the style or the content of the performances that constitutes the erotics — another unexpected trait that Madonna has in common with Clay.

Madonna’s aim throughout appears to be to straddle the barrier that separates the merely show-offy from the outrageous without falling squarely on either side — which may help to explain why she and her gay dancers gleefully chant that they want this to be an X-rated movie. Consequently, her solidarity with gay activists shines through the movie as a relatively unmediated sentiment, while her stance of refusing to censor her “Like a Virgin” number at a Toronto concert is undercut by whatever concessions were made to avoid getting an NC-17 rating.

I found her slinky glamour poses on her mother’s grave site a bit on the tacky side, but most of her other “outrages” are good-natured adolescent mischief — a desire to be naughty rather than dangerous (such as when she flashes her breasts at the camera while her father waits in an adjoining room for her to change clothes). And when it comes to playing mother hen to her staff, she’s responsible as well as silly. Most of the time, she’s playing the familiar star’s game of inviting you to join her pajama party while keeping aloof and exclusive, so that both positions ultimately become part of the act.

***

It’s easy to trash Dice Rules because the spectacle it offers is the closest thing I know in American movies to Nazi hate rallies — though I don’t know of any Nazi rallies where Jews applauded and cheered, and applauding and cheering women are quite visible in Clay’s audience. (Even the ones in the audience whom he openly objectifies — “Get up and show us your tits” — seem happy to go along.) In fact, it’s the documentary value of the shots of Clay’s enthusiastic public — a weird and significant sociological phenomenon in its own right — that earns this movie its only star from me; by contrast, the few shots of Madonna’s audience in Truth or Dare are instantly forgettable.

It’s important to bear in mind that, as Frederic Paul Smoler pointed out in the Nation last year, Clay’s routine is clearly being offered and accepted as a class statement. But going along with this gag — allowing Clay’s class to take all the heat for the misogyny and other forms of intolerance in this country — seems more than a little unfair. The damage done to women and women’s rights by the federal and state governments seems a lot more serious and lasting than the threat posed by the powerless and voiceless people who constitute Clay’s audience and cheering section. But in the case of Dice Rules, as well as in Alan Rudolph’s recent Mortal Thoughts and the new release Thelma and Louise (a movie I happen to like a lot), it’s the already exploited and already dumped-on working class that bears the full brunt of middle-class blame for the abuse of women in this culture — and those whose misogyny is more insidious and upscale are granted a free and guiltless ride.

I don’t consider myself blameless in this respect. When Presumed Innocent came out last year, I found its upscale misogyny much less deserving of censure than I do the blatant woman bashing of Dice Rules; like other middle-class people, I’m more susceptible to the iron hand when it’s cloaked in a velvet glove.

There’s a peculiar tendency in this media-happy culture to value the word or the image over the actual deed. Through some awful process of misplaced emphasis, we wind up showering more abuse on a comedian who spouts hate than we do on the actual rapists and wife beaters Clay is being held somehow responsible for, many of whose deeds go unremarked and unpunished. Clay becomes the fall guy because he’s much easier to target; the sheer coarseness of his routine, which is what endears him to his audience, is a lot more threatening to middle-class taste than Madonna’s make-believe sexual frolics with her gay dancers on her bed. But lavishing attention on him by turning him into a pariah — as the Loews theaters chain recently did by banning this movie from its 866 screens — may divert attention from the offenses that really matter.

Like most of the middle-class, I fear and despise Clay’s constituency; they remind me in many ways of the more vociferous supporters of George Wallace I encountered when I was growing up in Alabama. But when we start to single them out for blame for the worst aspects of our culture, like misogyny and racism, I think we go much too easy on ourselves and the goons we keep in office. A populist like Clay, Wallace inspired love in voters not for holding back integration but for standing in the door at the University of Alabama and pretending to hold it back — putting on a show, in other words, for frustrated, misguided people by giving voice to their rage. I’m not saying he didn’t do any damage to black people (or white people) in the process, but I doubt that he did a fraction of the harm done by J. Edgar Hoover or Ronald Reagan. What he did do was shout a lot, making him a perfect target for complacent, nonshouting Yankees who were perfectly content to go with the racist flow, as long as it had the right pedigree.

By the same token, I think it’s a bit skewed to grant to every real-life gesture Madonna makes the status of art, or to grant every performance gesture Clay makes the status of a real-life offense. I happen to agree with most of Madonna’s social agenda and disagree with all of Clay’s, but surely part of the point of the Bill of Rights is that everyone has a right to his or her opinions and attitudes, jerks included. The recent infringements on free speech on many college campuses may silence a certain number of jerks, but unless you’ve got a frighteningly efficient thought police at your disposal, you don’t get rid of opinions or attitudes by censoring them — you merely force them to go elsewhere. Dice Rules is one of those elsewheres — a Frankenstein monster that some of us may have helped to create.

Like Madonna, Clay clearly wants to be naughty and outrageous; unlike her, he isn’t interested in scaling that desire down to R-rated proportions and he’d probably lose whatever dubious singularity he has if he did. (I say “dubious” because, judging from the ten minutes I’ve seen of Eddie Murphy’s Raw — which wasn’t banned from Loews theaters — Clay is no more morally offensive than Murphy.) Consequently, Clay devotes his monologue to such topics as “bushes” (he doesn’t like them shaved or doused with cologne), “ass eating” (he impersonates Nixon doing same and grunting, “Be the pig that you are, baby”), and the contempt and malice he feels in general for women (all of whom he equates with whores), Japanese people (“Thank God for Donald Trump or the Japs would own everything,” though they do “know how to fold shirts” — a wisecrack that seems intended to show that he can’t distinguish them from the Chinese), people with disabilities (he democratically includes midgets, hunchbacks, twitchers, and stutterers in this category), and birds (he dreams of poisoning them).

What does he like? Himself (or so he claims), America (“the greatest country in the world”), funerals (“a good place to pick up chicks”), and obscene nursery rhymes. The nursery rhymes are the show’s true centerpiece; most of them are delivered in unison by the audience, giving a ritualistic feel to the proceedings that, like the rest of the performance, seems to have more to do with fellowship in bile and despair than with genuine laughter.

I’ve heard it argued that a hate mongerer like Clay can actually provoke violence against women; I’ve also heard it argued that he can prevent violence against women by allowing potential perpetrators to let off some steam. Both arguments ultimately strike me as begging the issue. In the screwed-up culture that we inhabit, all sorts of things are capable of provoking or preventing violence against women, and singling out Clay as either a scapegoat or a savior in this regard is tantamount to burying one’s head in the sand — the very option that most of the mass media is designed to offer.

Neither Truth or Dare nor Dice Rules dares to leave open any of the questions it raises. They offer themselves as flat assertions, and most reviewers follow suit by offering flat assertions about them — I have too, by assigning star ratings to each of them. How much truth is gained in the process? It’s questionable whether any of these flat assertions will alter the status of sex or tolerance or censorship or the social effects of art in anyone’s mind. At most, each movie will become a rallying point for an opposing constituency (though it’s hard to imagine that any constituency supporting Dice Rules will have a critic to call its own, unless Joe Bob Briggs decides to step forward). Eventually both movies will be forgotten, and new products will come along to make and elicit similar flat assertions. Meanwhile, as we let more movies persuade us that we’re dealing with important issues by arguing about them, more women will be raped and beaten, minorities will continue to be persecuted, and concerned citizens will call for new suspensions of the Bill of Rights.