This was written in late 2012 and early 2013 for Film Comment, but this magazine’s editor at the time loved to improvise the contents of every issue at the last moment, and this article had already been edited, scheduled, and then pulled from two separate issues. For me, it had currency and some immediacy because of the release of a Delvaux box set in Belgium; from the editor’s more land-locked Manhattan perspective, it could be published any time without making much difference. Rather than run the risk of this delay happening a third or even fourth time over the remainder of that year, and because I believed that jonathanrosenbaum.com (now jonathanrosenbaum.net) may have had a larger readership than Film Comment anyway, I decided to make a last-minute editorial decision of my own and posted it there, originally in August 2013, forfeiting the expected fee for the piece. (Like all my other texts, it subsequently got transferred here half a year later, at jonathanrosenbaum.net.) — J.R.

Part of the strength of André Delvaux (1926-2002) as a filmmaker is that, like the otherwise very different Samuel Fuller and Jacques Tati, he was already pushing 40 when he directed his first feature — having by then studied music, German philology, and the law, and also taught Germanic languages and literature before he became a pioneer in teaching film at Belgian state schools, where Chantal Akerman and Hitler in Hollywood’s Frédéric Sojcher (who has written a short book on Delvaux) were among his pupils, meanwhile playing piano to accompany silent films at the Brussels Cinémathèque.

In various ways, Delvaux’s cultivated and detached, standoffish protagonists tend to reflect this multidisciplinary background — the pianist hero of Rendez-vous à Bray, for instance, is seen at one point accompanying a contemporary screening of Fantômas — although these portraits, never wholly sympathetic, sometimes register as critiques (or autocritiques) of these characters’ passive-aggressive traits. (A friend of Cinémathèque director Jacques Ledoux, Delvaux wound up marrying the latter’s secretary, Denise Debbaut, who went on to become both a major force in Belgian television and an invisible collaborator on her husband’s work, reportedly as important to his filmography as Alma Reville was to Hitchcock’s.)

One reason why Delvaux isn’t better known outside his home turf, where he’s widely regarded as the greatest and most Belgian of Belgian filmmakers, is our difficulty in navigating (as well as sometimes distinguishing between) Flemish as well as French strands in that country’s culture — and part of Delvaux’s distinction comes from his roots in both. Born in a Flemish-speaking part of Belgium, he entered a French-speaking school at age six when his family moved. And the day before he died, at an international conference in Valencia, he spoke ruefully and at length about the potent cultural mix that characterized his country before it became a federal state where subsidies supporting Belgian filmmaking had to come from either the French or the Flemish community but never from both — a move which effectively banished Flemish cinema from most people’s awareness.

Delvaux’s first and still best-known feature, The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short (1965), is Flemish; his next three — Un soir, un train (1968), Rendez-vous à Bray (1971), and Belle (1973) — are French, but the first of these freely adapts a story by Johan Daisne, the Flemish writer whose novel Delvaux had adapted in his previous film, and the conflicts between Flemish/Dutch and French speakers (including the lead couple, played by Yves Montand and Anouk Aimée) are central to the plot; similarly, shifts between languages crop up frequently in the other shorts and features. Delvaux’s next two films — With Dieric Bouts (an extraordinary short essay from 1975, juxtaposing painting with film and past with present, in which Delvaux’s contrapuntal use of sound is particularly remarkable), and Woman in a Twilight Garden, a 1979 feature — were co-written in Flemish with Ivo Michiels, and the second of these broached the then-taboo subject of Flemish (and Belgian-Catholic) collaboration with Germany during World War 2. Delvaux next followed that feature’s French lead actress, Marie-Christine Barrault, to the U.S., to make a feature-length documentary in English about her next film, Stardust Memories, entitled To Woody Allen, From Europe with Love (1980) — the only Delvaux film mentioned above that I haven’t yet seen — followed by a feature mostly in French with Fanny Ardant and Vittorio Gassman (Benvenuta, 1983), set mostly in Ghent as well as Milan, and a final feature in French partially set in Flanders (L’oeuvre en noir aka The Abyss, 1988).

As noted above, we usually confront Belgium’s bilingual culture by ignoring the Flemish part — as I just did in the previous paragraph, by giving English titles to all the Flemish films — and sometimes confusing the country with France. But now that an excellent Belgian DVD label, Cinematek, has brought out most of Delvaux’s major work with English subtitles, in slim, handsomely designed trilingual editions (go here) — six of his seven fiction features, and four of his major shorts (with other extras, including part of the speech he gave the day before he died) on a seventh disc — this situation will hopefully change. The only missing fiction feature — my second favorite, One Night, a Train, which remains unavailable due to rights issues — is currently available at http://thepiratebay.se, but its presence on YouTube tends to fluctuate. (Most recently, I could find only a brief excerpt there.)

***

It’s both tempting and limiting to call Delvaux a Belgian surrealist — or, as many prefer, “magical realist”. French Surrealism is an actual movement but the other two categories are at most tendencies. For me, one significant difference between French and Belgian surrealism is that the former is in rebellion against the bourgeoisie while the latter virtually equates the bourgeoisie with the cosmos — but this latter position can’t really be identified in national terms, because Franz Kafka and Sadegh Hadayat, among others, seemed to share it.

Un soir, un train, the Delvaux film that comes closest to both Kafka and Hadayat, follows a Flemish linguist (Yves Montand) as he departs on a train to give a lecture in another town — first quarreling with his longtime French partner (Anouk Aimée), who walks away from him shortly before he leaves, but later unexpectedly joins him in his compartment, then mysteriously disappears from it while he dozes off. After the train stops in a desolate wasteland, things become progressively stranger as he gets off with an older and younger man and they eventually wander into a mysterious town. I’ve recently discovered that the “incomprehensible,” untranslated language they hear in this town is in fact Farsi — which has made me wonder whether certain affinities of the story with Hedayat’s nightmarish novella The Blind Owl might have prompted this inclusion.

***

More generally, Delvaux’s seamless transitions from waking life to dreams tend to follow an emotional logic that retroactively seems logical, even inevitable. In the same film, for instance, the hero’s failure to have a child and his inability to find his father’s gravesite together seem to have some relation to the younger and older men who turn up as the hero’s companions in the story’s increasingly terrifying second half. And the overall narrative development in The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short from normality to insanity is comparably unnerving. The schizophrenia of the hero in Daisne’s novel — a middle-aged lawyer with a family who teaches at a local high school, and is quietly obsessed with a graduating girl pupil — is established by presenting his story as a flashback from a mental asylum, but the film, far less guided by its first-person narration, introduces this schizophrenia so incrementally and ambiguously that we’re held in a queasy kind of abeyance, and can’t even be sure at the end whether or not he’s murdered his former pupil, after running into her at a hotel years later. (Meanwhile, he’s quit his job to become a court clerk and attended an autopsy, in both cases with obscure motivations.) The fact that he barely looks at her during their climactic dialogue in her hotel room is only part of what’s so weird about the scene. There are odd hints about his condition throughout the film, from his behavioral tics to Delvaux’s unconventional edits, but the fact that we can’t distinguish between his mental reality and our objective perceptions is a constant.

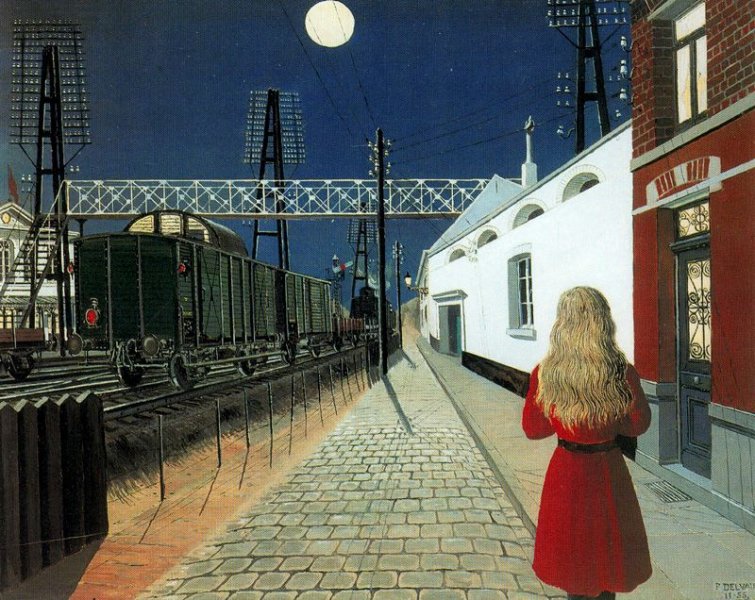

There’s a similar tendency in other Delvaux films, Belle especially, to switch from apparent objectivity to subjectivity and back again without clarifying when or how the transitions occur — although one of the more remarkable facets of Appointment in Bray is that it contains no literal fantasy, even in the Fantômas clip, yet virtually all of it feels magical. To cite Delvaux himself about the two best known Belgian surrealist painters (speaking to Dan Yakir in 1977), what he found striking in René Magritte was “the way he uses real elements in an illogical way,” and in his namesake [Paul] Delvaux, “the use of mystery, or settings I know well, old places with much charm, where people live as if they weren’t there.” At least two famous Delvaux paintings, Soledad (1955) and Trains du soir (1957), seem to have inspired a female nude on a railway platform in Belle, first seen in a dream with the title heroine (who may not even be real), and then evoked with the hero’s grown daughter in the “real” world, whose upcoming marriage and his anxiety about it is tied somehow to Belle’s unexplained appearances.

But Delvaux’s relation to music, informed by his virtually career-long collaboration with composer Frédéric Devreese, runs still deeper than his relation to painting. His art is largely composed of subtle structuring devices that work via emotions more than ideas (one of his many affinities with Alain Resnais), and sometimes their subversiveness is so subterranean that it seems to reach us via osmosis. Like Delvaux’s first feature, Belle and Benvenuta are both films about the central character’s sexual obsession, and the fact that this is related to incestuous impulses — the hero’s towards his daughter in Belle, Benvenuta’s towards her father — is partly conveyed through visual rhymes in the first case, editing patterns in the second. (Moreover, Benvenuta’s passion for an older man and father figure, played by Vittorio Gassman, who becomes her lover, is juxtaposed with the relation of an older woman [Françoise Fabian], a novelist, recounting Benvenuta’s fictional story to a younger man [Mathieu Carrière], a filmmaker, who wants to adapt it into a screenplay.) If we consider juxtapositions between repressed normality and kinky desires, a possible parallel between Belgium and Canada is suggested, at least if one considers the films of David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, and Guy Maddin. There also seems to be a common preoccupation with death and decay — ranging, in Delvaux’s case, from the rotten fruit at the end of the opening sequence of his first feature to his last film, the 8-minute 1001 Films (1989), included on Cinematek’s shorts DVD — dedicated to the Belgian Cinémathèque and largely preoccupied with the deterioration of celluloid.

***

My first encounter with his work was Appointment in Bray, which I now regard as his masterpiece (it was Delvaux’s favorite as well). It is his most subtle and delicate film, and is the hardest to describe. Based on a Julian Gracq novella, “Le Roi Cophétua” (an English translation of which is still in print), it has a dense Gothic atmosphere and even denser erotic texture that defy any synopsis — perhaps because, as Delvaux has pointed out, it is structured more in musical terms (specifically as a rondo) than as a narrative. It concerns a young pianist and musical journalist, Julien (German actor Mathieu Carrière), in 1917 Paris, receiving a telegram from his composer friend Jacques (Roger Van Hool) — who is in the air force-–inviting him to his country house in Bray, only a short distance from the battlefront. On the train, Julien — a noncombatant from neutral Luxembourg whose German accent provokes some hostility from the French — begins to recall various prewar encounters with Jacques and a fellow musician, Odile (Bulle Ogier, in one of her most delightful and inventive comic performances); there are hints of a potential ménage à trois that evoke Jules et Jim, albeit with far more sensual (and homoerotic) imagery; Jacques and Odile are already involved, but Julien seems to shy away from her sexual interest, and it’s suggested that he’s a virgin. Arriving at Jacques’ roomy mansion, Julien is greeted at by a mysterious woman (Anna Karina, at her most luminous) who says that Jacques hasn’t yet arrived, and serves him tea and then dinner. In fact, Jacques never turns up and the woman eventually takes him to her bed, but we never discover either her relation to Jacques or the reason for his absence, and in the morning Julien heads back to the train station, where he lets the train leave without him, then hesitates about his next move.

A perfect and exquisite work filled with question marks that somehow thrives on its multiple mysteries, Appointment in Bray leaves such a pungent aftertaste that, in spite of my reverence for Akerman, if I had to select a single Belgian film to take to a desert island, I’d pick this one in a flash. Undoubtedly part of what makes it so satisfying is the sheer musicality and dialectical charge of its eroticism — the way that the story in the present and its implied ménage à trois seem to resolve the sense of incompletion in the flashbacks without resolving much of anything in the storyline.

***

In the early 60s, Delvaux made four documentary miniseries for Belgian TV about Fellini, Jean Rouch, Polish cinema, and Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort, and these experiences undoubtedly helped to shape his subsequent features. A wonderful 40-minute episode from the latter, Behind the Screen, is included in Cinematek’s DVD of Delvaux shorts; in it we get to see Demy directing Gene Kelly and working with Michel Legrand on the score, plus a dance rehearsal and joint interview with Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac. Delvaux met the lead actress of his first feature, Beata Tyszkiewicz (Andrzej Wajda’s wife), in Poland, and from Rochefort he recruited an executive producer (Mag Bodard), cinematographer (Ghislain Cloquet — a Belgian who’d also done major work for Bresson and Resnais), and sound technician (Antoine Bonfanti, who’d also worked extensively for Resnais and Godard) who would all work with Delvaux a number of times.

With the exception of Belle — an original script written before Bray, but realized afterwards — all of Delvaux’s features are inspired by the fiction of contemporary authors with whom he corresponded, freely adapting their work with their approval. Reportedly at least half the plot of One Night, a Train is Delvaux’s own invention, and in Bray, he converts Gracq’s hero from a wounded French World War 1 vet into a Luxembourgian civilian who no longer narrates, and adds lengthy flashbacks that include an invented character (Odile). Like Stroheim working from McTeague to produce Greed, you could call Delvaux an adaptor more faithful to the spirit than to the letter of his sources, using his chosen texts as starting points for his own inventions.

***

Reading most of the few accounts of Delvaux’s work written in English — especially those by the late Tom Milne, probably his most sympathetic critic — one often gets the impression that all his features after his first were relative disappointments. This is the drift of Tony Rayns’ recent appreciation of The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short, and even Milne regarded the political turn in Woman in a Twilight Garden, a film about a Flemish Catholic youth leaving his French wife to collaborate with the Nazis, as a lapse (although arguably Delvaux was already critiquing Belgian society in The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short, One Night, a Train, and Belle, and would also critique its Catholicism in Benvenuta and The Abyss). These aren’t my biases, even though I’d concede that Delvaux’s last three available features are weaker than his first four.

The Man Who Had His Hair Cut Short may indeed be his most significant contribution to Belgian cinema, and it’s clearly a major advance over his 1962 short School Days, beautifully filmed but relatively slight. But I can’t say I love it the way I cherish Appointment in Bray, One Night, a Train, Behind the Screen, and With Dieric Bouts. (I haven’t yet seen either his experimental 1985 feature Babel Opéra ou la répétition de Don Juan or his 1986 short that grew out of it, La Fanfare a cent ans.) The feature that has so far engaged me the least is Delvaux’s final one, The Abyss — a grim tale about a Flemish doctor and alchemist in flight and in hiding during the Spanish Inquisition — but even this might well warrant a closer second look. No two Delvaux films are alike, and within my experience, they all prove to be far richer than they first appear.