From the Chicago Reader (September 8, 2006). — J.R.

13 (Tzameti)

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed and written by Gela Babluani

With Georges Babluani, Olga Legrand, Philippe Passon, Aurelien Recoing, Vania Vilers, and Nicolas Pignon

An English-language remake of this French thriller is already in development. But the film recycles so much I’d be surprised if it doesn’t get recycled in turn.

Fight Club has been cited as one of the key models for Gela Babluani’s 13 (Tzameti), but Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975) seems far more relevant, at least for its first half. In The Passenger an American journalist (Jack Nicholson) on an aborted assignment in North Africa encounters the corpse of a man he met earlier in his hotel and decides on impulse to take over the man’s identity, turning up for all of his appointments and seeing what happens. They lead into espionage and arms sales for a terrorist group, and as the journalist proceeds to Spain to keep the appointments, he does his best to elude people who are chasing him down in one or the other of his two identities.

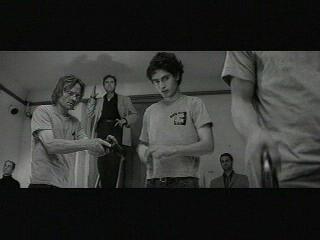

The hero of 13 (Tzameti), a 22-year-old Georgian laborer named Sebastien (Georges Babluani, a younger brother of the filmmaker), struggling in a French seaside town to support his family, is replacing the roof of a neighbor’s house when he overhears that the neighbor (Philippe Passon), a feeble morphine addict, is expecting a package in the mail that will make him and his wife (Olga Legrand) wealthy. When the man dies of a drug overdose Sebastien, learning that he probably won’t be paid for his work, intercepts the package and impersonates the man, following the instructions inside, which involve a train ticket to Paris, a hotel reservation, and more travel after he arrives. Meanwhile he has to dodge the police who’d been watching his neighbor.

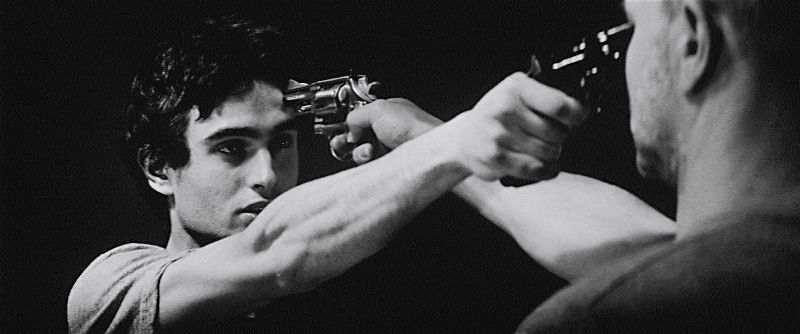

In the second half much of the film’s interest lies in viewers not knowing what’s coming, so you might not want to read further. For this section Babluani’s model appears to be Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) — specifically, the Russian roulette game that captured American soldiers in Vietnam are forced to play by sadistic Vietcong officers. Sebastien is obliged to play a similar sort of game, though here there are 13 players, each of whom has to point his gun at another player and pull the trigger while a few wealthy spectators bet on the winners and losers. Two bullets are inserted in the chambers of each survivor’s gun in the second round of the game and three in the third, and the player or players who are still alive at the end get to walk off with part of the winnings. (To calm their nerves the players are invited to shoot morphine between rounds, which may be what turned Sebastien’s neighbor into an addict.)

13 (Tzameti) might seem allegorical, but it’s too cynically concerned with what works as entertainment to offer larger truths about human existence. It’s not surprising that The Passenger and The Deer Hunter, both of which unfold in some kind of allegorical space, display a similar expediency. The Passenger comes from a period just after Antonioni abandoned the social realities of Italy — the subject of almost all his work between 1943 and ’64 — for metaphysical parables set in London (Blowup, 1966) and the American southwest (Zabriskie Point, 1969) and a documentary about China (1972). The Russian roulette game of The Deer Hunter was an effective if mechanical cheap shot, a suspense device invented by Cimino rather than an observation about the war in Vietnam.

Still, The Deer Hunter at least had a few things to say about working-class America before and after Vietnam. 13 (Tzameti) is supposedly set in France, and everyone speaks French, except when Sebastien and his family speak Georgian to each other. But the social and political climate, like the visual style of the black-and-white ‘Scope cinematography, is eastern European — especially the constant police surveillance, the omnipresent despair associated with poverty, and the gallows humor in response to capitalist corruption. And the defeatism of the final ten minutes is so pronounced we could just as well be watching a Russian gangster film.

Up to a point, The Passenger is true to an outsider’s view of North Africa and portions of Europe. 13 (Tzameti) could have told us something about what France looks like to a Georgian, but the elements that might have provided a precise social reality are instead being used simply to provide entertainment. And so a suspense sequence is just a suspense sequence. The English-language remake could make the gamblers Middle Eastern terrorists and it would hardly make a difference — at least as long as the relation to the real world is superfluous.