From the Chicago Reader (August 26, 2005). — J.R.

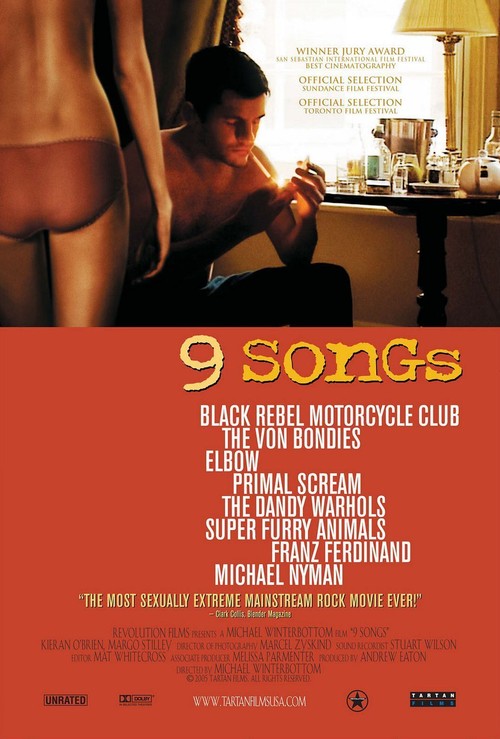

9 Songs

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Michael Winterbottom

With Kieran O’Brien and Margo Stilley

Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll used to be a commercially surefire package that today seems less automatically reliable. Which is presumably why Michael Winterbottom’s 9 Songs arrives in Chicago 15 months after its Cannes premiere — during the dog days of summer, when art-house films that distributors aren’t quite sure what to do with tend to surface. Sex is the main course, the side dishes are nine concert performances given by rock bands, and the spices are a few glancing references to cocaine and prescription drugs.

Even though it has few of the narrative elements we usually expect, this 69-minute movie is surprisingly fresh and original. The mise en scene, the editing (by Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross), and the camerawork by Marcel Zyskind keep it lively and attractive. The lighting is often exquisite, and the actors sometimes seem like inspired jazz players.

9 Songs is intermittently arousing, but though the sex is real, it isn’t really porn. Jonathan Romney offers a pretty precise description in the London Independent: “Essentially, 9 Songs bets us that it can make sex stand for all the other things that routinely convey character.” It’s a scriptless improv for two actors, one professional (Kieran O’Brien), one not (Margo Stilley), and whether what we’re watching when they’re getting it on qualifies as fiction or documentary is part of what keeps the film interesting.

Matt, who’s English, and Lisa, who’s American, meet at a mobbed Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert at London’s Brixton Academy, go back to his place to have sex, then continue to meet for sex over several months. We learn almost nothing about them: their snatches of dialogue are banal, and there’s hardly any story apart from the sex, which ends when Lisa decides she wants to fly back to the States. If this is a love story it’s pretty trite, and only Matt shows any sign of sentiment.

Matt studies glaciers for a living, but we never learn what Lisa does, though we hear that she’s 21 and can easily guess that he’s about a decade older. The action is framed through his narrated memories of her while he’s flying over or trekking across portions of Antarctica. I guess this pretentious framing device, and its supposedly poetic resonance, qualifies 9 Songs as an art movie rather than something more experimental and underground, but it feels tacked on.

Two BRMC songs played at the Brixton Academy — “Whatever Happened to My Rock ‘n’ Roll” and “Love Burns” — serve as bookends to the action. The remaining seven songs consist of bits of concerts Matt and Lisa attend over the course of their affair, at such venues as the Forum, the Hackney Empire, and the Hammersmith Apollo. The couple rarely moves outside the bedroom or the clubs, but a few breathers are provided by one glimpsed visit to the countryside and a pebbly beach and a few short forays to the kitchen.

In the 60s and early 70s movies with rock, hard-core sex, and not much else were what a lot of young people were dreaming about. Thirty years later 9 Songs arrives and is barely noticed, its transgressiveness so slight that it has about as much drama as a naked stripper slowly pulling off her wristwatch.

A friend once idly fantasized about a movie musical in which sex acts took the place of the song and dance numbers. Winterbottom’s film isn’t quite that, because he typically starts each sequence with an onstage rock song, then lets the music play over the sex before cutting back to the concert again. He doesn’t use extended takes or MTV fragmentation, settling instead somewhere in the middle: not entirely respecting the integrity of either the sex or the music, but not wanting to bore the audience with any systematic program.

The only things that are creative and expressive here are the sex and the music, yet both are so conventional they wind up seeming like minimalist performances. The selections, especially by Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, but also by the Von Bondies, Elbow, Primal Scream, the Dandy Warhols, and Super Furry Animals, seem locked into traditions that are decades old — including early Stones and light shows of the same period. My favorite number is Franz Ferdinand’s “Jacqueline,” in which the band’s body language and energy nearly rival O’Brien and Stilley’s. It’s followed by a completely anomalous piano solo by Michael Nyman at his 60th birthday concert, presumably thrown in for the sake of variety.

Ultimately each move toward breaking a barrier or assaulting a taboo is undercut by a reliance on conformity and convention. There’s raw sex, but also fashionable body types — the tense compactness of O’Brien, the lean androgyny of Stilley. To keep his film entertaining, Winterbottom tends to skirt any real sense of danger, anchoring every aspect of the milieu firmly in the generic. Nevertheless, because he dispenses with all the usual psychological and dramatic machinery, the actors’ performances and their interactions with the camera become unpredictable and existential.