From the Chicago Reader (March 4, 2005). — J.R.

Chain

*** (A must-see)

Directed and Written by Jem Cohen

With Miho Nikaido and Mira Billotte

Chain, the first solo feature by film and video artist Jem Cohen, is a strange mix of documentary and fiction about malls and similar commercial spaces. It’s meditative rather than action packed, and the creepiness it exposes has as much to do with absence as presence. But it deserves more attention than the single local screening it’s getting at Columbia College. I suspect it’s not getting more because it was partly funded by European television, because distributors never know how to package films that merge documentary and fiction, and because it belongs to the netherworld between film and art (it’s playing in conjunction with the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s exhibition “Manufactured Self”). It hasn’t even made the art-house circuit, which is a loss: it’s highly ambitious, has plenty to say, and is far from inaccessible.

Chain was shot in 16-millimeter over six years in hundreds of malls around the world — Atlanta, Dallas, Orlando, Berlin, Paris, Warsaw, Melbourne. That it’s impossible to tell the malls’ locations is part of the point. “I began the project,” says Cohen in his press notes, “by deciding to focus on the corporate and commercial landscapes that I had previously ‘framed out’ in my filmmaking, and to try to understand how these places were affecting the people within them. Wal-Mart, for example, opens a new store roughly every two days and yet the actual sites of such developments often take on a strange invisibility. Their presence can begin to seem inevitable and even natural. Rather than examining this phenomenon through the facts, experts, and arguments of the traditional documentary, Chain tells the stories of two women as this environment shapes their lives.”

The environment is aural as well as visual: over shots of urban details we hear a male British voice describing foreign investment trading through bank hookups between New York and Tokyo, and later we hear telemarketing ads left as voice messages. That we don’t know who’s receiving these messages contributes to the film’s eerie ambience.

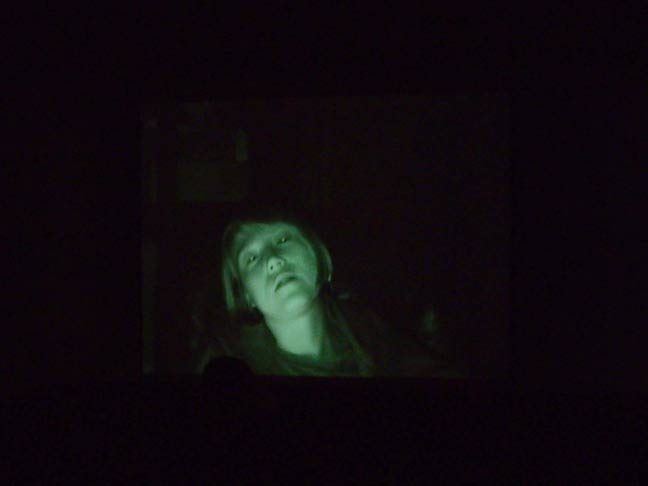

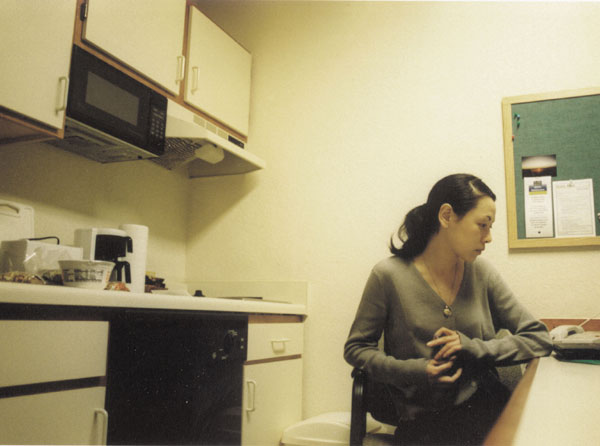

The two young women are shown almost exclusively as solitary figures. The first is Tamiko, a 31-year-old Japanese executive “set adrift by her corporation while studying the international theme park industry”; she’s played by professional actress and dancer Miho Nikaido (a Hal Hartley regular). The second is Amanda (Mira Billotte, of the New York band White Magic), a much younger, homeless American runaway who’s hitchhiked cross-country and run out of money and is now hanging out in a mall during the day and sleeping wherever she can at night, including a construction site. Tamiko’s story is titled “Business Trip,” Amanda’s “The Mall.” Both characters are fascinating, but if this film has a serious flaw, it’s that only Amanda seems fully realized and believable.

The two characters are conceived somewhat didactically as alienated zombies who embody different classes and cultures, convenient pegs on which Cohen can hang his observations and feelings about malls. He sees malls functioning as private, noncommunal spaces that isolate people from each other — one reason he shows his heroines alone, trapped in their own private worlds. (Cohen shot most of the film without the malls’ permission, which may have informed his depiction of Amanda’s fear of being observed and Tamiko’s spiritual isolation.)

It’s startling to learn that Tamiko is an unabashed racist: she speaks of “so much wasted space and so much [racial] mixing” and says that “without a pure race it will be difficult to have a pure goal for business. In the U.S., factories are built where there will be less mixing and more racial harmony.” As we hear her saying this offscreen, we see her walking across a lawn toward the camera, shortly before we see three black people cross the screen in a different direction. But her remoteness from her surroundings is complicated by a desire to relate. It’s funny to hear her report that some Americans think of Sony as an American company. “Maybe we share Sony the way that America shares Disneyland,” she concludes.

Despite such details, I can’t fully accept Tamiko as a fictional character. Cohen (whose work includes films on Fugazi and Elliott Smith) is a documentarist at heart, like the two filmmakers his film is aptly dedicated to, Humphrey Jennings and Chris Marker. And although he’s a seasoned world traveler, he still clearly can’t understand a Japanese character as well as he can an American one. Tamiko narrates her story in English, but given that she describes how difficult it was to learn, it’s peculiar that she talks to herself in that language.

Amanda is a lot easier to accept on all levels because we don’t feel that Cohen had to invent as much when he imagined her. Much of the time she’s making a video, addressed like a letter to her half sister, with a camera she found in the mall. Keeping the camera, she explains, was simpler than trying to find its original owner. She has no fixed address and supports herself by working as a maid at a motel. (Later she starts sharing a motel room with two other young women.) In one of her most telling scenes, she describes finding a broken cell phone and discovering that when she pretended to talk on it mall security was apt to leave her alone. She says that sometimes when she feels she’s being watched too much she takes a bus to another nearby mall and hangs out there.

One striking precedent for playing fiction against powerful documentary footage is The Savage Eye, a 1959 black-and-white independent feature cosigned by Joseph Strick, Ben Maddow, and Sidney Meyers. (Unlike Chain, it played in art houses when it came out, just as John Cassavetes’s documentarylike Shadows did around the same time.) It meshes the story of a fictional, alienated divorcee (Barbara Baxley) with documentary footage of life in Los Angeles shot by several remarkable photographers, including Haskell Wexler, Jack Couffer, and the extraordinary Helen Levitt. Like Chain, it’s narrated mostly by two voices — a disembodied quasi-authorial male voice (Gary Merrill, pretentiously identified as “The Poet” in the credits) and that of Baxley (whom Merrill addresses and questions in the manner of a confessor). The offscreen text is mannerist purple prose, but still the film is unjustly forgotten today.

Like The Savage Eye, Chain uses documentary images to create a powerful sense of time-capsule reality that’s often ethnographic and apocalyptic in its implications. The fictional reveries seem intended to anchor, understand, expand, and comment on that reality, which they do with varying degrees of success. As the film focuses on familiar, everyday details in the malls, it achieves a certain monumentality by making those details terrifying, forcing us to feel we’re in free fall, annihilating our sense of where we are.

When: Fri 3/4, 7 PM

Where: Columbia College Ludington Bldg., 1104 S. Wabash, room 302

Price: Free

Info: 312-344-6708

More: Cohen will attend.