From the Chicago Reader (December 3, 2004). — J.R.

Bright Leaves

*** (A must-see)

Directed and Written by Ross McElwee

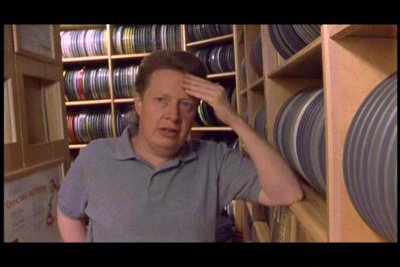

As a filmmaker who’s always philosophizing about his family, his southern heritage, and the meaning of life, Ross McElwee can get a little high-flown at times. The funniest shot in the latest installment of his autobiographical saga, Bright Leaves, brings him down to earth a bit — and shows that McElwee actually may have learned something from the deflation. The shot occurs toward the end of the film and there are several reasons it’s so funny.

(1) A noisy dog is following McElwee as he threads his way through a kitschy sculpture garden, whose relevance to the story remains obscure. Is it cemetery statuary? Whatever it is, it’s a visual and narrative non sequitur that only adds to the screwball ambience.

(2) The growling dog, seen near the lower edge of the frame, recalls a smudgy, minimalist black-and-white comic strip drawn by David Lynch between 1983 and ’92, The Angriest Dog in the World. (The graphics of the four panels in each strip were almost identical — the same dog angrily pulling at the same chain in a fenced-in backyard — but the introductory words and the balloons of dialogue coming from someone unseen inside the house were always different.)

(3) McElwee complains offscreen that the appearance of the dog “ruined the shot,” then does a second take showing him calmly traversing the same space without it.

(4) Both takes come right after the most deflationary moment for McElwee in the film. Up to this point his central premise has been that Bright Leaf, a 1950 Gary Cooper feature about a 19th-century tobacco baron, was based on the life of McElwee’s great-grandfather John, who developed the Bull Durham brand in North Carolina, then got cheated out of his fortune by his main competitor, James Buchanan Duke. The scene with the dog comes right after McElwee visits the elderly widow of Foster FitzSimons, the man who wrote the source novel for Bright Leaf, and she tells him that her late husband didn’t base it on a real-life story, John McElwee’s or anyone else’s. “I can promise you it ain’t so,” she insists.

(5) Our sense of McElwee’s defeat is underscored in light of details from some of his previous films. In the 1996 Six o’Clock News, for example, he disapproves when a film crew twice restages its entrance into his Boston apartment. But of course both takes of McElwee crossing the field had to have been shot by someone else, so he too is guilty of a certain amount of documentary staging and fakery. He clearly knows this. His larger point is that movies have a mythical power, and whether they’re unexceptional Warners releases like Bright Leaf or documentaries like Bright Leaves, they inevitably mix fact and fiction.

When I reviewed Six o’Clock News in these pages in April 1998 I was more than a little irritated that McElwee used the human disasters highlighted by the six o’clock news as a way of generating material for his autobiographical movie. Six o’Clock News is framed by reflections about his son Adrian between the ages of one and four and interspersed with his own philosophical ruminations. It also includes a couple of appearances by his former teacher Charleen Swansea, the most memorable of the recurring characters in his work. A onetime protege of Ezra Pound, Swansea was the focus of one of McElwee’s first films, the 1977 Charleen, and she figures significantly in Bright Leaves. Given McElwee’s implicit acknowledgment that his life becomes valid film material only when it bounces off universal subjects — which is also implicit in his Sherman’s March (1986) and Time Indefinite (1993) — I wondered if his exploitation of human suffering in Six o’Clock News wasn’t much different from that of the TV news.

One could say that tobacco plays the same ambiguous structural role in Bright Leaves that human disasters played in Six o’Clock News, but this time McElwee seems on top of the ironies involved. He begins by recounting a dream he had about being surrounded by enormous plant leaves, like the tobacco leaves that are connected in his mind to the south he misses. (A North Carolina native, he’s been teaching filmmaking at Harvard since 1986.) Then during a visit to a second cousin, this small-town lawyer, film buff, and film collector suggests that Bright Leaf is actually a movie about their great-grandfather. In the remainder of Bright Leaves McElwee investigates the meaning of this potential legacy.

McElwee was once a smoker, briefly when he was younger, and he still feels “slightly tempted” by the “kind of trance state” smoking produces, a state he compares more than once to the one induced by watching a film — but that proves somewhat incidental to his research. More relevant may be his family history: he comes from a family of physicians, and he explores the parallel legacies of his father and grandfather, who treated the physical ravages of tobacco use, and of his great-grandfather, who sought to make a fortune from tobacco. The parallel themes of success and failure in the McElwee and Duke families seem quintessentially American and not merely southern, as does the “success” of having one’s life ratified by a movie — a notion that’s never far from this movie’s core.

One reason Bright Leaves is McElwee’s best film since Sherman’s March is the richness of his reflections on this multifaceted material — which may say as much about the tainted legacy of cinema as it does about that of the deadly weed. He can make room on his bustling canvas for both Patricia Neal, Cooper’s costar in Bright Leaf, and film theorist Vlada Petric, a onetime Harvard colleague.

Like the cranky dog, both Neal and Petric have their doubts about McElwee’s mission. Neal speaks of Cooper as the love of her life and understandably sees Bright Leaf as an emblem of her own life rather than of McElwee’s or of his ancestor’s. Petric argues on behalf of the kinesthetic pleasures of film and complains that the director of Bright Leaf, Michael Curtiz, “doesn’t have a cinematic vision.” (Maybe, but Curtiz did like to move his camera around; I wonder if the late filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who at the time he died was planning a book on Curtiz, would have agreed with Petric.) Perhaps Neal and Petric are simply expressing two versions of the same wisdom — that we all turn movies into personal emblems of one kind or another.

Note: Ross McElwee sent the following correction, which appeared as a letter to the editor in the December 24, 2004 issue.

Dear Jonathan,

Thanks for your insightful article about Bright Leaves and for making it the “pick of the week” [“Smoke and Mirrors,” December 3]. I believe that helped quite a bit in boosting attendance that first weekend.

Just wanted to point out one extremely minor but interesting factual error in your review. You state that “of course both takes of McElwee crossing the field had to have been shot by someone else.” In fact, I did shoot both takes myself. There was no one there but me (and a small, somewhat vicious puppy). I placed the camera on a tripod and framed the shot I wanted. I then started the camera, sprinted to a position off frame, and began my walk. At the end of the shot, having momentarily vanquished my canine opponent, you can see me approaching the camera and giving a hand slate before leaning over the camera to turn it off. I always do my own camera work. On rare occasions I have worked with a sound recordist, but 99 percent of the time I work alone. I guess I believe that the notion of the filmmaker protagonist as a solitary, sometimes perplexed figure puzzling through life as he makes his filmed journeys is important to how my films work and to their skewered sense of veracity. The larger point you are making, of course, still stands: all movies, to varying degrees, mix fact and fiction, and Bright Leaves is, among other things, certainly an exploration of that idea.

Thanks very much for your interest in and support of Bright Leaves.

Ross McElwee