From the Chicago Reader (April 2, 2004). This wonderful documentary, incidentally, is now available on the Criterion DVD of Pickpocket. One of its most fascinating paradoxes for me is that Mangolte, a friend, isn’t a religious person, but this documentary strikes me as profoundly spiritual; Lasalle’s home is even treated as a sacred shrine. — J.R.

Les modèles de “Pickpocket”

***

Directed and written by Babette Mangolte

With Pierre Leymarie, Marika Green, and Martin Lasalle.

Not until he was in his late 90s did Robert Bresson get the recognition he deserved. He died in 1999 at the age of 98, living long enough to see his work affirmed by a retrospective the Toronto Cinematheque’s James Quandt organized that traveled around the world to full houses.

For years mainstream critics regarded Bresson as esoteric, pretentious, even something of a joke. “The chief fault is that the hero is a vacancy, not a character,” wrote Stanley Kauffmann in one of the more sympathetic reviews of Bresson’s 1959 Pickpocket, a free adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. “Martin Lasalle, who plays the part, has a bony, sensitive face, but no deader pan has crossed the screen since Buster Keaton. The besetting fallacy of modern French films and novels is the belief that nullity equals malaise and/or profundity.” And though not intended as hostile, the description offered by Leonard Maltin’s Movie Encyclopedia, quoted on the Internet Movie Database, is no less representative: “One of the most rigorously ascetic directors in film history, Bresson eschewed any overt stylistic flourishes whatsoever, employing wooden but distinctive-looking nonactors to perform lead roles, and telling extremely simple, often pointedly despairing tales detailing the ruination of pure souls in a cruel world.”

I find Bresson’s films highly physical and even carnal rather than ascetic. And the only thing wooden about the three principals in Pickpocket — Lasalle, Pierre Leymarie, and Marika Green, all of whom are interviewed by Babette Mangolte in her video documentary Les modèles de “Pickpocket” — is their lack of mugging. Bresson originally called his carefully chosen nonactors “interpreters,” later settling on “models.” He was more interested in capturing who they were than fussing with what they might want to project as performers, and all three were willing to follow his rigorous instructions to serve his art.

“I notice that the flatter an image is, the less it expresses,” Bresson wrote in 1959, “and the more it transforms itself in contact with other images. A film should be something in a state of perpetual birth.” The expressiveness of performers, locations, and individual shots got in the way of that perpetual birth, so Bresson brought out their more latent qualities — in the case of the performers, their souls or spiritual essences. All three were apparently transformed by the experience. (Two of them went on to become occasional actors in the films of others, as did Dominique Sanda, Bresson’s best-known model, the star of his 1969 Dostoyevsky adaptation, Une femme douce.)

A mysterious, aloof figure, Bresson said he started out as a painter, but to my knowledge no one has ever seen any of his paintings. I got to work for him as an extra in 1970 — on Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), his third Dostoyevsky adaptation — and he seemed more isolated from his crew than any other filmmaker I’ve seen at work; his widow and onetime assistant director, Mylène van der Mersch, often conveyed his instructions. Bresson was reticent about his background, and van der Mersch has kept such tight control over his legacy that an official biography seems unlikely. Yet I’ve heard from usually reliable sources a startling claim about his early life that, if true, would help to explain a few things: that he worked briefly as a gigolo.

Though impossible to prove, it seems plausible, given his good looks and some of the moral preoccupations of his work, above all his first major feature, the 1945 Les dames du Bois de Boulogne. (That feature as well as his next, the 1950 Diary of a Country Priest, have recently appeared on excellent Criterion DVDs, and I’m told that many others are on the way.)

We definitely know that Bresson spent over a year as a prisoner of war in a Nazi internment camp — the subject of one of his greatest films, A Man Escaped (1956). His imprisonment seems to have had a strong impact on his later work, apparent in his taste for offscreen sound and his special feeling for souls in hiding.

“How is it possible to confuse a film with life?” asks an offscreen Mangolte in English at the beginning and end of her investigation. Born in France and educated in Paris, Mangolte has spent most of her life in the U.S. (she’ll discuss Les modèles de “Pickpocket” at the Gene Siskel Film Center screening Thursday, April 8). She’s best known for her remarkable cinematography in films by Chantal Akerman, Richard Foreman, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Marcel Hanoun, Sally Potter, Jackie Raynal, Yvonne Rainer, and Michael Snow. Her own experimental films often concern subjectivity and landscape — What Maisie Knew (1975), The Sky on Location (1982) — and have been unjustly neglected.

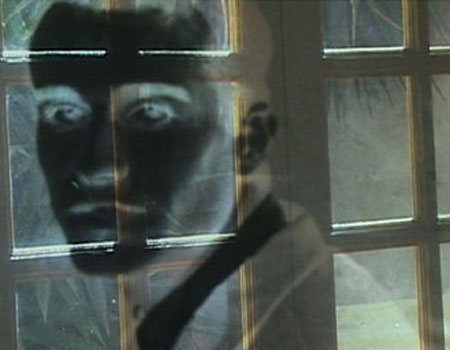

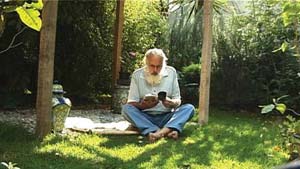

These issues are embedded in Les modèles de “Pickpocket” — the most beautiful of her works I’m familiar with, one that deserves to be called a poetic personal essay as well as a documentary. In the opening scene, a party in Paris where she knows only the host, she spots Pierre Leymarie and realizes she knows him from somewhere; he tells her he was in Pickpocket, which she says is her favorite film. At his invitation, she travels to Caen to interview him about his experiences with Bresson some 40 years earlier, picking up clues that lead her next to Marika Green (the film’s 16-year-old female lead), in rural Austria, and finally to Lasalle, in Mexico City — a cheerful, white-bearded mystic who dominates the second half of the video. Given how disturbed Lasalle’s character in Pickpocket, Michel, is — he’s an alienated college dropout who masters the art of being a graceful pickpocket — it may be as surprising to us as it is to Mangolte that he seems so much at peace with himself.

Mangolte seems to imply that it’s possible to confuse Bresson’s films with life because they’re made up of its very substance. She suggests this subtly in her own style, without ever doing any obvious imitations, whenever she focuses on the immediate surroundings of her interview subjects: Leymarie’s empty living room, the view from Green’s window, Lasalle’s garden. Lasalle is last seen giving us and Mangolte an impromptu tour of his neighborhood before vanishing into a crowd.

All three models seem utterly self-aware and self-possessed and seem to remember the filming of Pickpocket as if it happened yesterday. (The same is true of the two former Bresson models I’ve met: Florence Delay, his Joan of Arc in 1962, who now teaches literature, and Isabelle Weingarten, from Four Nights of a Dreamer, who works mainly as a photographer.) Green, who pulls out her copy of the shooting script, reveals that the film originally had a more existential title, “Incertitude.” She admits to having been in love with Bresson at the time, but also insists that he had “old-fashioned manners” and respected her, even as she surmises that she may have avoided meeting most of his subsequent female models out of jealousy.

Lasalle says working with Bresson was the greatest experience of his life, even though he once had to climb stairs through 40 retakes. He calls “Bressonian” Manoel de Oliveira’s The Letter and Jean-Louis Trintignant’s performance in Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Red, and he alludes to Paul Schrader, perhaps the American filmmaker who’s been most clearly influenced by Bresson’s work. The memorable lean and hungry look Lasalle conveyed as Michel may be lost in his joviality and middle-aged spread, but he still comes across as a seeker.

Lasalle confirms in passing the startling idea that Charlie Chaplin was one of the few other directors Bresson liked. One might ask how cinema’s greatest master of expressive acting could have been admired by a director who suppressed expressive acting. A partial answer may lie in the reason avant-garde filmmaker Jean-Marie Straub gave for his startling contention that Chaplin was the greatest editor in the history of cinema: Straub said Chaplin knew precisely when a gesture began and when it ended. Bresson not only appreciated that talent but possessed it — it’s one of the things that makes him great too.