From the Chicago Reader (October 31, 2003). — J.R.

Sylvia

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Christine Jeffs

Written by John Brownlow

With Gwyneth Paltrow, Daniel Craig, Jared Harris, Amira Casar, Andrew Havill, Lucy Davenport, Blythe Danner, and Michael Gambon.

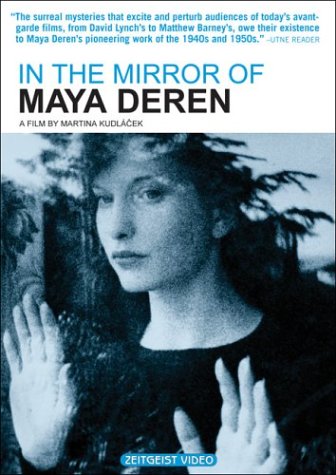

In the Mirror of Maya Deren

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Martina Kudlacek

Greasing the bodies of adulterers

Like Hiroshima ash and eating in.

The sin. The sin.

— Sylvia Plath, “Fever 103 °“

In film, I can make the world dance.

— Maya Deren

In college it always seemed like the guys who were poets got more girls than the prose writers. The assumption was that poets had all the romance and sensuality associated with their medium working for them. Poetry, after all, isn’t just a block of printed material; it’s an activity, and one that can turn people on sexually as well as spiritually.

In cultures such as those of Russia and Iran sexual and spiritual qualities tend to run neck and neck: the great Persian poet Forough Farrokhzad (1935-’67), a fan of Sylvia Plath, retains a mythic allure that combines the auras of Joan of Arc, Billie Holiday, and Marilyn Monroe. And an erotic charge is one of the first things that Sylvia, a biopic about Sylvia Plath (1932-’63), gets right. It pervades the initial encounters between the title heroine and Ted Hughes in Cambridge, England, in 1956. The film arrives at these meetings with exemplary dispatch, after opening with Plath’s excruciating declaration in “Lady Lazarus”: “Dying / Is an art, like everything else, / I do it exceptionally well.” The brisk action that follows and the lack of fuss over exposition gave me some assurance that director Christine Jeffs and screenwriter John Brownlow knew what they were up to.

Todd McCarthy writes in Variety, “There’s a big piece missing from the picture’s center: The all-encompassing connection that brought the couple together in the first place is never made palpable.” I disagree. The couple’s shared passion for poetry, depicted mainly in small but telling details, is certainly an all-encompassing connection, though I can’t swear those details are made palpable for everyone.

I object more strenuously to McCarthy’s opening gambit — “As grim as much of Sylvia Plath’s life may have been, it wasn’t as relentlessly bleak as the movie Sylvia” — which I’d probably find presumptuous even if it came from one of her friends. Of course presumed knowledge about her life has been a central aspect of the Plath myth ever since her suicide at 30, which helped to bring that myth into being — especially for those who’ve fetishized her as a prefeminist martyr. I find nothing bleaker about the life of Plath and Hughes than something this movie pointedly, if understandably, omits: Assia Gutmann Wevill (played in the film by Amira Casar) — with whom Hughes lived after he separated from Plath and with whom he had a daughter, Shura — killed herself and Shura six years after Plath’s suicide, when she was 34 and Shura 2. She turned on the gas in her kitchen stove, just as Plath did. It’s worth adding that Wevill was a poet, and that, according to Paul Alexander’s biography Rough Magic, the “burden of living in the shadow of Plath” played a significant role in motivating her act.

The terrible thing about Plath “dying exceptionally well” is that her suicide appeared to clinch her fame — as if the poetry she wrote wasn’t quite enough. I remember how angry I was when one of my professors argued that her suicide “proved” many of the assertions of her poems, giving them a legitimacy they wouldn’t have had otherwise. Whether one buys this theory or not, it points to the factor that dooms most literary biopics, including serious ones — the all but obligatory tendency to privilege the life over the work. In this case the filmmakers had legal restrictions on how much they could quote from Plath, guaranteeing that the space for her poetry would be small. (As partial compensation, we get a fair sampling of other people’s poetry, including Chaucer’s.)

Considering the myth making that has surrounded Plath’s reputation from the outset, a dispassionate view of her life has never been easy, and the film’s most admirable achievement is its refusal to take sides in the dispute between her and her late husband, viewing both with sympathy and compassion. One of the best aspects of Gwyneth Paltrow’s finely tuned performance is her capacity to convey Plath’s chronic depression without making us recoil from it, and Daniel Craig takes on the task of representing Hughes’s womanizing with a comparable feeling for complexity and nuance. Making this couple’s relationship more important than their poetry surely wasn’t the movie’s intention, but it becomes the central program nonetheless. And this locks the movie into an imposture, because without their poetry we wouldn’t know or care about their relationship.

One reason it’s an imposture is that cinema and poetry aren’t merely disparate art forms but largely incompatible ones. (Farrokhzad’s only film, The House Is Black, is the only successful fusion that comes to mind.) Poetry has to be read slowly — one of the things that makes it sexy — and even though some great films move slowly, commercially minded biopics do so at their peril. Consider the three short lines from Plath’s “Fever 103°” quoted above or any five-line stanza from “Daddy,” another desperate late poem, written a week before “Fever”: the poetry must be allowed to reverberate — to drift and spread, line by line and word by word. And how many movies that star Paltrow have the time for that? Indeed, as I’ve suggested, one of the nicest things about Sylvia, at least in the beginning, is its unusual speed. Yet speed is ultimately relevant only to storytelling; it has almost nothing to do with composing or reading poetry, except when it’s recited as quickly as possible for laughs, as happens in one early scene here.

The problem is, people’s lives aren’t stories. They have to be turned into stories to become fodder for biopics, and the interpretations that shape them are likely to be determined by the needs of dramaturgy. I’m no expert on Plath’s life, but even a superficial skimming of Rough Magic reveals that her mother played a much larger role in her life than the film’s mother (Blythe Danner, the real-life mother of Paltrow). The film uses her character mainly to offer exposition about Plath’s past during her sole appearance, when Sylvia brings Hughes home to meet her; once that task is gracefully accomplished by Danner, she’s not allowed to interfere with the story again.

I can’t imagine what a biopic about Maya Deren (1917-’61) — the person who did the most to create American experimental film as we know it — would be like, and I hope I never have to find out. One of the best things about In the Mirror of Maya Deren — a feature-length documentary in English by Austrian director Martina Kudlacek, playing at the Gene Siskel Film Center a dozen times this week — is that it does such a terrific job of showing us what Deren was like that it makes even the notion of a biopic about her seem unnecessary, if not ridiculous.

For one thing, Deren so assiduously chronicled and recorded her filmmaking activities and lectures that Kudlacek had a lot to work with. She makes wonderful use of the material, though lamentably a private recording of Deren singing the standard tune “Mean to Me” has been cut since I first saw the film in early 2002. Deren’s version doesn’t threaten Sarah Vaughan’s, but it’s a collector’s item to cherish. I suspect it had to go because the cost of paying the song’s copyright holders was too high. The song is still mentioned in the final credits; maybe it was too expensive to redo them. Fortunately the film has a wonderful original score by John Zorn, which makes dramatic use of suspended chords, as well as other samples of Deren singing and several pieces of music she recorded during her four trips to Haiti between 1947 and 1955.

Money was always something of a problem for Deren, at least as an adult, though she was the first filmmaker to ever win a Guggenheim Fellowship grant. She died of a brain hemorrhage at 44, and one of her friends suggests that malnutrition may have been a contributing factor — along with amphetamine shots and a legal dispute involving the inheritance of her 26-year-old Japanese lover that evidently exercised her fiery temper.

Born Eleanora Derenkovskaya in Kiev the year of the Russian Revolution, she had a privileged upbringing as the daughter of Russian Jews, a psychiatrist father and a mother who studied music. When she was still a child the family moved to Syracuse, New York, and in her early teens she attended a Swiss boarding school. But by the time she finished her formal education, in 1939, she was a bohemian poet and working as a secretary. “I was a very poor poet,” we hear her say in the film, “because I thought in terms of images…[and] poetry is an effort to put [visual experience] into verbal terms. When I got a camera in my hands, it was like coming home.”

Perhaps her most consequential secretarial job was for dancer and anthropologist Katherine Dunham, one of the many fascinating talking heads here; it took her to Los Angeles, where she met the Czech experimental filmmaker Alexander Hammid (another talking head). Collaborating with Hammid, she made her first film, the groundbreaking Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) — a series of metaphorical and metaphysical self-portraits as rich in Freudian content as any of Plath’s late poems, though made mainly in celebration and without any of Plath’s self-loathing. (This film and most of Deren’s others, which are all liberally sampled in Kudlacek’s film, will be showing at the Film Center on Monday and Wednesday, making it possible to catch them just before or after the documentary.)

Deren saw female self-portraiture as a process of perpetual metamorphosis — an explicitly feminist undertaking that’s in some ways the opposite of Plath’s petrified notions of identity. Clearly the world wasn’t quite ready for that sensibility; neither of the best American film reviewers at the time, James Agee and Manny Farber, was any sort of fan, though the larger art community she was part of — including dancers, choreographers, musicians, composers, and other filmmakers — encouraged and supported her.

This milieu is brought to life so vividly in the documentary one can almost smell the kitty litter in Deren’s Greenwich Village flat. Better yet, the film performs the nearly miraculous feat of allowing us to know her as a person as well as understand her as an artist, and it does this better than any of the excellent books about her, including the two volumes to date of The Legend of Maya Deren — a massive, collectively authored biography and compilation that’s been in the works since the 80s — and the recent collection Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde.

A high-strung narcissist and sensualist who anticipated hippie dress codes as well as New Age babble, Deren might seem to gather all the cliches of bohemian Manhattan in the 40s and 50s in one Jungian jumble. Yet the robust power of her charisma is conveyed so affectionately by her friends, even when they recall her with exasperation, that something all her own arises out of the overlapping archetypes she adopted.

If Plath’s myth is the creation of her writing — magnified by her suicide and the depths of depression her writing explored — Deren’s myth is the product of a steady rush of evolving self-definitions. Those definitions can’t be restricted to her films, though the films provide the ideal settings for them. The late Stan Brakhage, who knew her well and provides the most sensitive and provocative appreciation of her films in the documentary, offers a startling view of her as a kind of demiurge when he describes watching her lift and hurl a full-size refrigerator across a kitchen in a moment of rage.

Even if we balk at believing him, we may conclude that the force of her personality was such that it could inspire this sort of belief. In Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde Jane Brakhage Wodening, who recounts the same story, suggests as much when she writes about Deren, the words spilling out as if she were in a trance: “In Haiti, she was fulfilled. She learned about voodoo, a religion of shamanic power, and this religion was based on dance. And when she danced in Haiti, she was possessed of the voodoo gods and she had power over men. And so she became a priestess and her red hair stuck out all over her head like sparks and she wore her hair that way the rest of her life.” This may sound like it belongs in a Cecil B. De Mille opus or in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, but it does suggest the effect Deren had on others. It’s sad that Plath could exert that kind of power only posthumously, which puts it beyond the reach of any biopic.