From the April 25, 2003 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

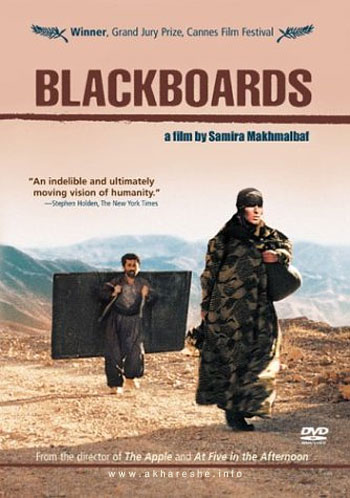

Blackboards

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Samira Makhmalbaf

Written by Mohsen and Samira Makhmalbaf

With Bahman Ghobadi, Said Mohamadi, and Behnaz Jafari.

I don’t know why it’s taken three years for Samira Makhmalbaf’s second feature to reach Chicago. It was finished in 1999 and won the jury prize at Cannes the following year. The Iranian director was only 17 when she finished her remarkable first feature, The Apple, which also screened in competition at Cannes and made her one of the youngest directors ever to gain an international reputation. Since then, she has made the 11-minute “God, Construction and Destruction,” about the responses of Afghan refugee children in Iran to the attacks on the World Trade Center, which is part of the 2002 international episodic feature 11/09/01 (still unscreened in the U.S.). She has also made the feature At Five in the Afternoon, about a young woman in post-Taliban Afghanistan, which is expected to premiere at Cannes in May.

All of her features to date have been produced, edited, and written or cowritten by her father, Mohsen Makhmalbaf. But the three films of hers that I’ve seen are significantly different from his in that they deal with communities more than individuals, and I happen to like The Apple more in some respects than any film directed by him. She has also had an increased role in the writing of each feature and is credited as an equal partner on the Blackboards script, completed when she was 20. Mohsen wrote the story outline for At Five in the Afternoon, but Samira is credited as sole author of the script. (You can download some outlines and scripts in English from the Makhmalbaf Film House Web site, www.makhmalbaf.com.)

Makhmalbaf Film House — the eccentric Iranian film school founded by Mohsen in 1996 with a student body consisting of eight family members and friends — has already yielded several notable films, most recently The Day I Became a Woman (2000), directed by Marziyeh Meshkini, Mohsen’s second wife. Mohsen is both a former fundamentalist and a national hero, which gives a special edge to his school’s utopian agenda.

When I first saw Blackboards three years ago I was surprised as well as puzzled that in some ways it reminded me of John Ford’s 1950 western Wagon Master. I’ve since tested that impression by watching Wagon Master again, and I’ve found even more substantial parallels to Blackboards in Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s most recent feature, Kandahar (2001). These parallels seem worth exploring.

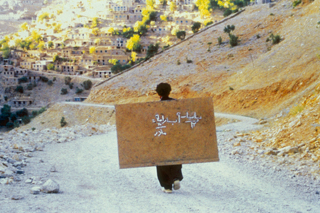

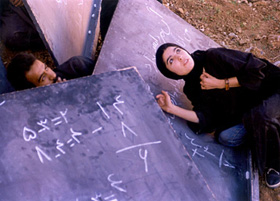

Set in the rocky wilds of Kurdistan in northern Iran near the Iraqi border, Blackboards (playing several times this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center) focuses on a group of Kurdish teachers, all men, who carry blackboards on their backs as they search for students, wandering from one remote outpost to another. One teacher, Reeboir (Bahman Ghobadi, the writer-director of A Time for Drunken Horses), latches on to a group of teenage boys smuggling goods from Iran to Iraq. They rebuff most of his efforts to teach them to read, write, and do math, though we eventually discover that some of them already know how to read and write but are wary of admitting this to a stranger. Another teacher, Said (Said Mohamadi), joins a larger group of old men searching for their homes. One of the men is accompanied by his widowed daughter Halaleh (Behnaz Jafari) and grandchild, and he persuades Said to marry Halaleh immediately so that he can die in peace.

This meandering, episodic movie also features overhead helicopters, armed soldiers, and chemical weapons, from which many of the Kurds are fleeing. It evokes Kandahar in that it’s set near the border of another country — Iraq instead of Afghanistan — and is concerned mostly with hardship and grief. It also belongs to a curious and contradictory subgenre that Mohsen Makhmalbaf has been specializing in — one might call it documentary fantasia–which includes his Gabbeh (1997) and “Testing Democracy” (codirected by Shahabodin Farokh-yar, 2000) and Meshkini’s The Day I Became a Woman (produced and scripted but not edited by him). Samira Makhmalbaf confirms this impression in a press-book interview about Blackboards, noting, “The film’s story pivots between reality and dream. The smuggling of contraband goods, wandering, and the people’s struggle to survive are real. For the character of Halaleh, I was inspired by the life of a woman whose husband was killed. I asked the actress to study closely that woman’s way of being.”

This subgenre can be puzzling for many Westerners, since it’s often impossible to separate fact from fancy. A pronounced surrealist streak rubs shoulders with the documentary actuality of location shooting in many of the details — about carpet weavers in Gabbeh, about the group of women bicyclists and the elderly shopper who has her goods delivered to a beach in The Day I Became a Woman, about the woman dropped from a plane to collect votes in “Testing Democracy” (which inspired the story of Babak Payami’s Secret Ballot), about the one-armed man hiding with a book under a burka in Kandahar. The very first image in Blackboards — of the flock of teachers carrying their blackboards across a mountain pass –has the same sort of uncanniness, and it’s nearly matched by the final image, of Halaleh crossing the foggy Iran-Iraq border with a blackboard on which is written “I love you.” Is the fog actual fog or poisonous gas? Are we meant to take it allegorically or literally — or both? My acquaintance with Persian literature is limited, but this kind of ambiguous magic-realist poetry can be traced at least as far back as The Arabian Nights; it’s certainly abundant in Sedegh Hedayat’s exquisitely creepy 1937 novel The Blind Owl.

It can also be difficult to sort out fact from legend when it comes to westerns. The ambiguity in Blackboards relates to recent history, but both it and Wagon Master are intended to appeal to our mythic imaginations. Part of the rough parallel I find between them can be seen in critic and filmmaker Lindsay Anderson’s description of Wagon Master: “Ford often abandons his narrative completely, to dwell on the wide and airy vistas, on riders and wagons overcoming the most formidable natural obstacles, on bowed and weary figures stumbling persistently through the dust.” None of the figures in either film is on a religious pilgrimage, but in both, persecuted minorities — Mormons in Wagon Master, Kurds in Blackboards — flee across a wilderness toward some hope of a promised land, which gives their journeys religious overtones. In Blackboards the teachers can be seen as semireligious figures — rather like clergymen in search of congregations — and the old men call to mind a lost tribe, though the young smugglers come across like members of some downtrodden gang.

Both films highlight the uneasy and sometimes antagonistic temporary alliances between existing groups and outsiders traveling together and suffering many of the same hardships, and in both cases the outsiders frame our view of the groups: the two horse traders (Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr.) hired by the Mormons as wagon masters, and the two teachers tagging along with the separate groups of old men and smugglers. Both films have a haunting sense of existential drift that’s apparent in some of the homier details: in Blackboards the use of walnuts as currency, the difficulty an old man has taking a piss, and the methods of performing an impromptu marriage ceremony; in Wagon Master the importance of shaving to a medicine show proprietor in a top hat and the pleasure taken by a matriarchal figure in blowing a horn.

A Kurdish-American acquaintance told me he was offended by the depiction of Kurds as primitive in Blackboards, and I wonder if any Mormons feel the same way about Wagon Master — though Ford soft-pedals the issue of bigamy and reportedly pared away details that showed Mormon prejudices. In both cases our view is strictly touristic — and because most of us are also tourists when we watch Iranian cinema, we wind up viewing Blackboards through two filters.