From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 2002). — J.R.

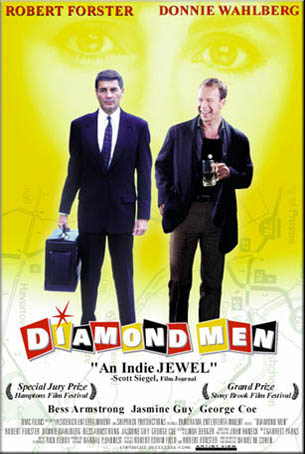

Diamond Men

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Daniel M. Cohen

With Robert Forster, Donnie Wahlberg, Bess Armstrong, Jasmine Guy, George Coe, Jeff Gendelman, Nikki Fritz, and Shannah Laumeister.

It’s astonishing how few Hollywood movies tell us anything about the way we spend a third or more of our lives — at work. Maybe this is because the standard industry perception is that people don’t like to think about that part of their existence when they go to movies, that people want to keep their professions and pleasures separate and mutually alienated. The assumption seems to be that work isn’t supposed to be fun but movies are.

Since I don’t have this bias, I found myself uncommonly excited watching Diamond Men, an independent first feature by writer-director Daniel M. Cohen that stars Robert Forster and is playing this week at the Music Box. I have no particular interest in the diamond trade, but I was thrilled to have the opportunity to see a movie that taught me something about what it’s like to drive through small towns in Pennsylvania selling diamonds to jewelry stores — especially since its lessons are being propounded by someone as knowledgeable about the subject as Cohen (who, reports Philadelphia Inquirer film reviewer Carrie Rickey, is a third-generation diamond man from Lancaster) and articulated by an actor as likable as Forster.

Cohen has found a great American subject with potentially epic dimensions, and though only the first third of the movie makes it the main bill of fare, the sense of vast reaches that pervades this section carries over to the rest. I don’t want to suggest that we’re inundated with facts and figures or given a seminar on the subject. “I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg,” Ernest Hemingway once said in an interview. “There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg.” This is true not only of Cohen’s storytelling but of Forster’s acting; he can imply more with shrugs and eye movements than most actors can manage with their entire bodies.

Forster plays Eddie Miller, a widower with two grown daughters. We never catch even a glimpse of his family, and just about all we ever see of his house’s interior is his kitchen — because the visible part of Cohen’s iceberg is Eddie’s life on the road, which he’s been living for the past 30 years. This life is threatened in the film’s opening minutes, when he suffers a heart attack next to his car in a parking lot. Because this makes him harder to insure, his company wants to put him out to pasture, but his supervisor lets him stick around long enough to train a rookie.

The rookie, Bobby Walker (Donnie Wahlberg), is less than half Eddie’s age, and his opposite in most respects: he prefers rock to jazz and carousing with waitresses to having a good woman at home, and his braggadocio seems calculated to affront Eddie’s quiet, low profile. (Wahlberg serves to offset Forster’s minimalism with diverse kinds of excess, something he does with style and gusto.) Nevertheless the two gradually become buddies as Eddie teaches Bobby the trade.

The plot thickens when Bobby tries to repay his mentor by taking him to a whorehouse Bobby periodically visits and helps advertise, and the story becomes increasingly preoccupied with what diamond men do in their spare time. This part of the film has an undeniable authenticity, though the animated wink of a large eye tattooed between the breasts of a prostitute attempting to service Eddie that seems designed to accentuate his skittishness is a distracting, uncharacteristically glib stylistic pirouette. In most respects, however, the storytelling is sure and unfussy, and the fact that it doesn’t look much like Hollywood is almost entirely to its credit, because practically every step away from studio norms is in the direction of truth and economy. When executing jump cuts, for instance, Cohen always seems to know what he’s doing, and his preference for advancing the story through them rather than making them part of the usual facile slickness is refreshing.

This movie has been getting marginalized by the mass media in the most punitive way possible, simply for not being a Hollywood picture — which in practical terms also means not having much of an ad budget. It played a few east- and west-coast venues last fall and garnered some enthusiastic reviews, but was omitted from most end-of-the-year critics’ polls. (Ignoring non-Hollywood product is a principal preoccupation not only of entertainment journalism but of the tax-supported American Film Institute, which I suspect failed to include Charlie Chaplin’s sublime Monsieur Verdoux as a candidate in its tacky poll of the 500 best American sound comedies simply because it was an independent production.) Diamond Men gets unusually close to the experience of a lone, taciturn, middle-aged salesman — Forster’s powerfully nuanced and subtly textured (if stoical) performance offers an encyclopedia of observations on the subject — which may be another reason the media aren’t treating it with the kind of respect they routinely give teen comedies with fart jokes and Oscar winners that confer nobility on the act of murder. I guess a movie that confers nobility on the process of growing old doesn’t have enough excitement.

It might seem at first that Diamond Men loses its bearings once it strays from examining the strategies and reflexes of diamond salesmen, but the transactions between these men and the prostitutes aren’t all that different. For the most part, the prostitutes are nicely observed. Katie, the second whore Eddie encounters, the one he falls for — a New Age nurturer beautifully played with the faintest touch of affectionate satire by Bess Armstrong — is as finely detailed as any of the men in the movie. The same is true to a lesser extent of Tina (Jasmine Guy), the young madam. But then the movie makes the mistake of showing us another hooker, Cherry, with her lowlife boyfriend and his partner in crime; this brief step beyond the world and viewpoints of Eddie and Bobby to explain an important plot move shows how shockingly little sense of reality Cohen has once he’s outside his own class and milieu. The problem isn’t so much that Cherry, her boyfriend, and his sidekick are repulsive or irredeemably evil — creeps of this kind undoubtedly do exist — but that Cohen’s interest in them ends as soon as their plot function is over. No other character in the movie is dismissed in this way, which makes the three of them stick out like sore thumbs.

The film’s climactic plot twist, which I won’t divulge, is another possible point of contention. This isn’t because it seems more Hollywood than anything else in the picture; it’s because Cohen deceitfully tampers with his hero’s motivations in the course of setting the whole thing up. He clearly likes Eddie and the other two principal players in this story so much that he wants to reward them, and it’s hard not to share his good feelings about them.

Cohen reports that Eddie was basically inspired by his father, and I suspect that most people have some version of an Eddie, a Bobby, and even a Katie kicking around in their lives. Diamond Men may wind up close to fantasy, yet it’s a fantasy that we sense has been lived.