From the Chicago Reader (November 12, 1999). — J.R.

Romance

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Catherine Breillat

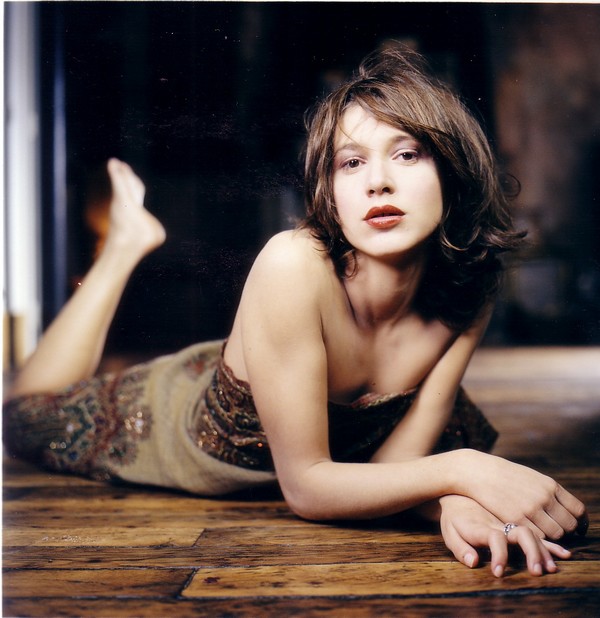

With Caroline Ducey, Sagamore Stevenin, Rocco Siffredi, and Francois Berleand.

I’ve never put much stock in my powers of prophecy, but it seems I was more off the mark than usual nine months ago when I emerged from the world premiere of Catherine Breillat’s Romance, in Rotterdam, thinking it would create a sensation if it reached the U.S. I somehow forgot that most movie sensations are the fabrications of publicists. Audiences can create sensations — The Blair Witch Project proves that — but reviewers, who are usually closer to publicists than to audiences, are often the last people to notice. So maybe Breillat’s seventh feature did cause a sensation with audiences when it opened in New York several weeks ago, but if so, I don’t think it’s been reported.

Nine months ago I decided that Romance was a pretty reactionary movie for France — mainly because of an offscreen statement made by the heroine near the end (“They say a woman isn’t a woman until she’s a mother; it’s true”). But I still thought it might be seen as progressive in America, especially because its rare confluence of cinematic taste, literary intelligence, and hard-core sex might undercut the crippling puritanism of our movie codes, which usually equate eroticism with porn, sleaze, and stupidity rather than, say, art, health, and intelligence. I also thought it might provoke a few instructive skirmishes with our main movie censors, the Motion Picture Association of America, an organization run by and for the Hollywood studios that exposes its double standards just about every time an independent or foreign-language picture comes along.

I still think Romance is a progressive movie in America, even though it was (sensibly) released without an MPAA rating. But many of my colleagues disagree. Judging from their jaundiced disparagements, most of them are bent on shrugging this movie off as a piece of silliness; some of them even admit to preferring entertainments like Dogma, which have the trendy advantage of being both American and conceived by and for people with the mentality of an 11-year-old boy. It’s hard to see how word of mouth can compete with millions of dollars of hype being shoveled into viewers’ gullets on a daily basis, particularly when most reviewers seem to owe more allegiance to the shovelers than to the viewers. If millions of dollars had been spent hyping Romance, American reviewers would undoubtedly be taking it more seriously and according it more column inches.

Or so I thought when I read some of the New York reviews last month. But I have to admit that Romance didn’t look as good to me when I saw it again last week. Was this simply because the movie isn’t as good as I’d thought, or was it a function of the country and cultural climate I saw it in? For starters I would argue that what we call good and bad in movies can’t exist apart from cultural climates.

The plot of Romance is ridiculously simple. Marie (Caroline Ducey), the narrator and heroine, is a grammar-school teacher in Paris who lives with a male model, Paul (Sagamore Stevenin), whom she loves and desires. (The apartment they share is clinically white, suggesting at times a lab.) Paul insists he loves her but no longer wants to have sex with her, at least for the time being.

In desperation more than retaliation, Marie picks up a stranger named Paolo (Italian porn star Rocco Siffredi) for a night of sex, then becomes involved with the principal at her school, Robert (Francois Berleand), who boasts that he’s made love to 10,000 women in spite of his mediocre looks and who binds and gags her with her consent. In between two bondage sessions with him, she’s seen masturbating in her flat while crying and confessing offscreen that she doesn’t like her body and that this makes her easy prey. After spying on Paul having dinner alone in a restaurant, she accepts a stranger’s offer of 100 francs to let him go down on her; this takes place on the stairs of her and Paul’s apartment house and is followed by rougher and less friendly sex. (“Turn over, slut!” the stranger says. “Whore! Bitch!…I reamed you good.” She cries after he leaves, angrily calling after him, “I’m not ashamed, asshole!”)

After her second session with Robert, which concludes with their feasting on caviar and vodka at a Russian restaurant, she returns home and finds Paul suddenly interested in having sex; after briefly demurring, she climbs on top of him. According to her, this gets her pregnant.

Months later we see her examined by a doctor and several interns, then Paul proposing to her. Later scenes show Paul’s indifference to her as anything but a mother and her fantasy of guillotine-like contraptions dangling women’s legs and crotches that are fondled and penetrated by men. Paul has passed out from drinking when she goes into labor, so Robert takes her to the hospital. Before she leaves she turns on all the gas jets in the flat; she gives birth to a son at the same time the apartment explodes. Over a highly stylized coda depicting Paul’s funeral that’s even more informed by fantasy and metaphor, she announces that she’s named her son after his father. “If someone in heaven is counting souls,” she says, “we’re even.”

I think it means something that I first saw Romance in a country where it’s less difficult and dangerous to buy a joint than it is to buy a handgun, because this suggests something about the nature of pleasure and passion in the Netherlands and the U.S. And despite all the pronounced cultural differences between the Netherlands and France, I don’t think people in either country experience quite the same split between mind and body that many Americans do. This may be why the poetic “inner voice” of Marie that we hear jabbering away about the nature of sex during almost all of the film’s sex scenes –except the ones with Robert, whose on-screen dialogue serves a comparable function — would probably seem relatively natural and normal to many French viewers, borderline acceptable to many European viewers, and close to intolerable to many American (and British) viewers. Americans are much more likely to regard this kind of talk as pretentious, which may have something to do with a prevalent conviction in this country that mind and body are hopelessly at odds with each other — something that may also account in part for the rabid anti- intellectualism of American pop culture. This sensibility isn’t shared by most Europeans I know, and it seems to be even less evident in Latin countries. It’s worth adding that a different kind of sexual etiquette predominates in these countries as well. In Paris, for instance, it’s almost never considered bad manners for men or women to stare at other people in public places, either out of sexual interest or for other reasons — something I found enormously liberating when I lived there in the early 70s.

In any event, sexual and philosophical conventions ultimately become film conventions. It’s possible, for instance, that the wordless opening sequence of the western Rio Bravo — the freedom to rely on images alone — is intrinsically American, as are the taciturn qualities of western types ranging from Gary Cooper to Clint Eastwood. And it’s equally possible that the offscreen narrators who play such a key role in French cinema, fiction films and documentaries alike, reflect a reliance on spoken language that’s quintessentially French — a conviction that images are never quite enough to explain or bear witness to the world, coupled with a taste for poetry that prefers the high-flown to the mundane and the exalted to the merely expository. Yet this conviction doesn’t typically yield a split between mind and body; rather it creates a kind of musical counterpoint, a dance performed by the two, and, at least to my taste, a sensuality of thought — an idea at odds with the American notion that thought is an alternative to feeling and action.

As a consequence, all the pontificating about sex in Romance might pose an obstacle for some Americans, as might its somewhat primitive sexual politics — France is in many respects a prefeminist country, even though it has produced feminist thinkers ranging from Simone de Beauvoir to Christine Delphy and perhaps more talented women filmmakers than anywhere else in the world. This results in a kind of women’s cinema that might be considered backward by the usual American standards, but an audience less bound by middle-class propriety might see it as liberating.

Born in 1948, Breillat started out as a writer. She finished her first novel at the age of 17, and when she published it three years later its subject matter and language were considered so licentious it could be sold only to readers who were 18 or older. Eight years later she finished her first film, an adaptation of her third novel that was never released because the production company went bankrupt. She has also published a play in iambic hexameter and three more novels, the most recent of which is adapted from her third feature film, 36 fillette. And she has worked as a screenwriter for, among others, Liliana Cavani (La pelle), Federico Fellini (And the Ship Sails On), and Maurice Pialat (Police).

I can’t remember much about 36 fillette (1987), the first Breillat film I ever saw — a coming-of-age and losing-of-virginity tale about a precocious and obsessive 14-year-old girl and her involvement with a middle-aged playboy — but it irritated the hell out of me, and I couldn’t shake it. I knew women who liked it a lot more, and in general I suspect that Breillat’s films speak to women more than men — one of the things I find most interesting about them, because there just aren’t many such films, especially not ones that contain hard-core sex. (Truthfully, I find parts of Romance arousing, while other parts leave me cold — and I suspect this will be the response of most men and women.)

Serious movies that have sex in them are rarely treated seriously by Americans nowadays — compare the critical response in this country to Last Tango in Paris (1972), which Breillat acted in, and In the Realm of the Senses (1976). Romance isn’t nearly as good as these films. But it’s worth noting that In the Realm of the Senses, the better of the two, was Breillat’s main inspiration, and its influence is visible. (Six years ago she wrote an article about Oshima’s masterpiece for Cahiers du Cinema.)

The last unrated and relatively serious sex movie to be released here was Paul Verhoeven and Joe Eszterhas’s 1995 Showgirls, and it wasn’t received at all seriously. The critics hooted it off the screen as a piece of camp, just as many of them, including me, had dismissed the previous Verhoeven-Eszterhas sex movie, Basic Instinct, as a hoot. I now believe that both pictures hold up much better than anything we said at the time would have suggested. Showgirls has to be one of the most vitriolic allegories about Hollywood and selling out ever made, and both films are undeniably sexy to boot. (Incidentally, two of the biggest fans of Showgirls, both unapologetic, are Jim Jarmusch and Jacques Rivette.)

This response, as well as the derision that greeted Norman Mailer’s best film, Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987) — perhaps the most underrated American film of the 80s — suggests that Americans tend to get nervous about movies involving sex and tend to crack jokes, make dismissive remarks, and pretend to display a sophisticated urbanity about sexual matters to cover up their embarrassment. Why shouldn’t the ironically titled Romance make Americans nervous too?

I’m not entirely exempt from this tendency; I find the glum patter and absurd sexual boasting of Robert, not to mention the methodical way he sets about tying up and gagging Marie, in some ways comical. It’s likely that Breillat is aware of some of the potential comedy, even if she’s poker-faced about it, but probably not all of it. Americans may think that seeing the humor in such things is indicative of a broader sense of freedom, but I’d argue that the American rejection of certain sexual possibilities through laughter isn’t necessarily more sensible, mature, or healthy than the French acceptance of a wider range of sexual possibilities through avoiding laughter.

Assuming that both the body and the mind can profit from being challenged, and that the challenges of one don’t necessarily negate the challenges of the other, Romance offers a lot to think about and play with. We’d be fools to reject this bounty out of hand — unless we really are the middle-class cowards some reviewers assume we are.