From the October 22. 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

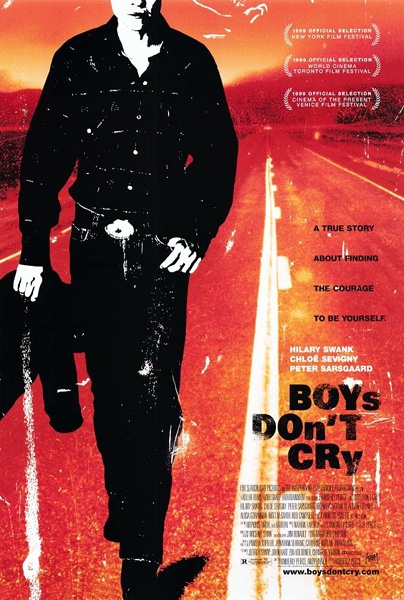

Boys Don’t Cry

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Kimberly Peirce

Written by Peirce and Andy Bienen

With Hilary Swank, Chloe Sevigny, Peter Sarsgaard, Brendan Sexton III, Alison Folland, Alicia Goranson, and Jeannetta Arnette.

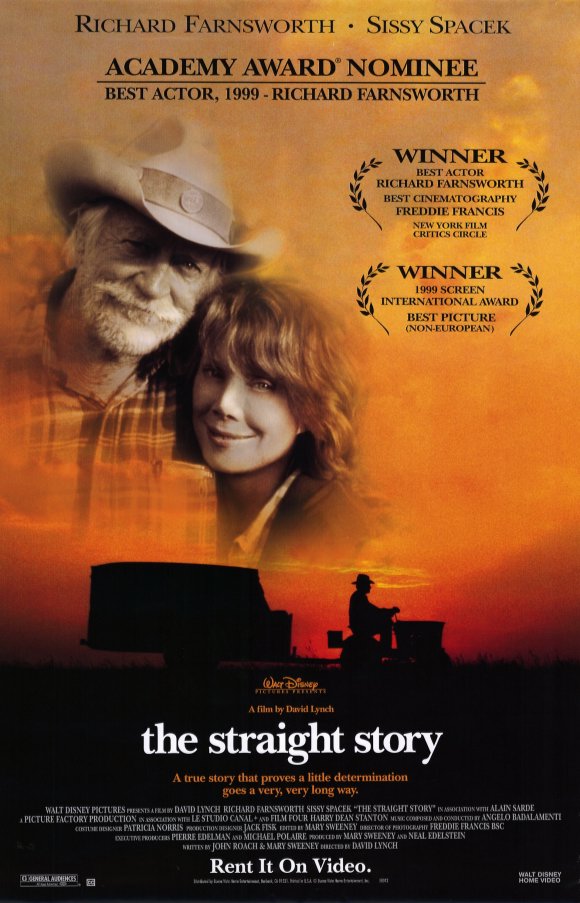

The Straight Story

Rating *** A must see

Directed by David Lynch

Written by John Roach and Mary Sweeney

With Richard Farnsworth, Sissy Spacek, Jennifer Edwards-Hughes, James Cada, and Harry Dean Stanton.

The docudrama may be the key dramatic form of the 90s because of the extent to which its simplifications influence the way we make sense of the world around us. Not that we didn’t already have a habit of simplifying and therefore fictionalizing facts. There are perfectly good reasons most of us prefer to believe that one day in December 1955 Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, because her feet were killing her, thereby launching the civil rights movement. This story has a germ of truth, but Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. had mapped out their basic strategy for the Montgomery bus boycott at Highlander Folk School in Tennessee well before this incident. Still, the more folkloric, more dramatic version of the episode is the one that sticks — and the one that’s repeated by people who want to explain the civil rights movement in more forcible, more legible terms.

This mythologizing impulse also shapes the telling of more recent history. One new film takes on the story of 21-year-old Teena Brandon, who was raped and murdered in Falls City, Nebraska, in 1993 for impersonating a man. Another tells the story of 73-year-old Alvin Straight’s almost 240-mile journey on a lawn mower from Laurens, Iowa, to Mount Zion, Wisconsin, to visit his ailing brother, in July and August 1994. Such stories are almost invariably imbued with meaning by the press before we get most of the facts, and when filmmakers get ahold of them, they tell them in even broader and more mythological terms, their desire for legibility so strong that all sorts of information interfering with clarity gets ground underfoot. What emerges may have a certain truth — morally as well as aesthetically — but it nevertheless functions as propaganda.

The propagandizing is obvious in the Teena Brandon movie, Boys Don’t Cry, where practically everything we see and hear conspires to feed our outrage at the sexual intolerance of other characters in the story. (Even before Brandon’s death was reconfigured as movie material, it functioned as a contemporary parallel to the 1955 case of Emmett Till, the black teenager who was brutally murdered for flirting with a white woman in Mississippi, only a few months before the launching of the Montgomery bus boycott.) But I doubt many viewers would think of The Straight Story, a Disney release directed by David Lynch, as propaganda — if only because, like many other Disney products, it’s steeped in a traditional national mythology that finds simple folk wisdom inspirational. Yet if it didn’t have a pronounced ideological thrust — and a fairly, if likably, reactionary one at that — I doubt that the American mainstream press would have been quite so scandalized by its failure to get a prize in Cannes, especially after the top prize went to its ideological opposite, Rosetta: a skeptical, leftist, and anything-but-transcendental Belgian feature about contemporary working-class struggle. In retrospect, the gesture must have seemed tantamount to spitting on the American flag.

I can’t tell you much about how The Straight Story fiddles with the facts of Alvin Straight’s life, because most of what I know about his life comes from the movie. But I can alert you to a casual lie in the movie’s press book. The first sentence of the section called “about the production” reads, “It was Mary Sweeney who discovered the story of Alvin Straight from reading The New York Times in 1994.” Sweeney is the film’s cowriter, coproducer, and editor as well as Lynch’s companion. She also produced Michael Almereyda’s Nadja, and it was Almereyda who saw the news story, clipped it, and sent it to Sweeney. Not a serious lie in any respect, but symptomatic of the way “extraneous” information is systematically weeded out of many docudramas. The extraneous information about Straight that gets weeded out of The Straight Story includes all the things he did for a living, apart from the fact that he grew up on a farm and fought in World War II.

What were these things? According to Susan Bosch, who interviewed Alvin’s son William for the Cedar Falls Courier Pulse, they included “bounty hunter, farmer, rancher, carpenter, and coal miner.” Apparently the film leaves out such basic information because it adheres to a principle of narrative economy, which it then turns into a kind of spiritual economy, as well as an invitation to the viewer’s imagination. As beautifully played by Richard Farnsworth — a wizened geezer coaxed out of retirement to play this part — Alvin Straight is a man of few words, all of them fairly well chosen, and the little he has to say about his life comes to us in carefully spaced and measured increments, implying that when you get to be his age you no longer have to jabber away about inessentials.

By comparison, it’s easy to get information about Teena Brandon, thanks to Aphrodite Jones’s 1996 nonfiction book All She Wanted (optioned, incidentally, by Diane Keaton) and other sources, such as Jared Hohlt of Slate. For starters, the name Brandon Teena is a posthumous invention of the press that Boys Don’t Cry adopts as part of its fictionalizing process: Hohlt insists Brandon never used Teena as a surname.

Of course this raises the question of what personal pronoun to use for Teena Brandon, something the movie doesn’t have to worry about because it assigns the task of labeling to its other characters. In All She Wanted Jones solves this dilemma by using masculine or feminine pronouns depending on Brandon’s social status at different stages, on how Brandon was identified in the surrounding community. I’ve already referred to Brandon as a “him” when there’s no question that biologically “he” was a woman. One reason I broach this problem is to suggest that it’s impossible to recount what happened in real life or even what happens in the movie without making some kind of political decision; indeed, most of this movie’s uncommon power as agitprop stems from the fact that you can’t watch it without taking sides.

Yet the Boys Don’t Cry press book doesn’t say a thing about what details in the movie had to be fictionalized or why. I assume legalities must have played some role in the changes, but making the profile easy to digest for purposes of agitprop must also have been a factor. Why else exclude fascinating (if emotionally confusing) material from Jones’s book such as the fact that Teena tried to enlist in the army to take part in Operation Desert Storm but failed the entrance exams or that after Teena’s murder her mother set up a fund to get her child a headstone and “some [transgender or gay activists] were willing to help out, but not if the headstone read Teena Brandon….For them, Brandon Teena was a latter-day Joan of Arc.” And why else exclude such distracting information as the fact that one of two other people killed along with Teena Brandon was Phillip DeVine, a black man with an artificial leg who was involved with the sister of Teena’s girlfriend (another omitted character)?

The above notwithstanding, Boys Don’t Cry is a powerful piece of social protest, skillfully written, directed, and acted — Hilary Swank as Brandon and Chloe Sevigny as his girlfriend Lana are especially fine — and every bit as harrowing as it intends to be. But the movie is as much about working-class life as it is about sexuality, which complicates its social message: one might emerge from it screaming for the blood of rednecks as well as weeping for some of their victims. One of the most shocking parts of the film is the interrogation of Teena Brandon by a sheriff after she was raped, much of which comes verbatim from the recorded interrogation of Brandon by Sheriff Charles Laux. Certainly more than one of the yokels in this story deserves our undying contempt. But to compare the political efficacy of this movie’s distortions with the political efficacy of, say, the distortions that surround the stories of Emmett Till or Rosa Parks, I’d have to be able to see what they might someday yield in terms of legislation about hate crimes.

If The Straight Story has an ideological message — and I believe it does — it can be construed as nearly the flip side of the message of Boys Don’t Cry. Though Teena Brandon didn’t see herself (or, more to the point, himself) as a lesbian, the movie’s message is gay activist. Lynch’s movie is a religious allegory about the triumphant survival of Middle America, seen mainly through a protracted rite of passage and configured principally as the endurance of the heterosexual family. This doesn’t mean that The Straight Story is homophobic. But it does mean that a sense of Eternal Verities, beginning and ending with a starry sky, hovers in the background throughout, and this has sexual as well as philosophical implications.

An early indication of what the movie has in mind is given when Straight encounters, feeds, and advises a young hitchhiker who’s five months pregnant and fleeing her family and boyfriend, none of whom knows that she’s pregnant. After recounting how his daughter Rose lost her own children, Straight tells the girl a brief parable about how sticks are breakable but bundles of sticks, like families, are impossible to snap, and in the morning he finds that she’s left him a bundle of sticks as a sign that she’s decided to heed his wisdom and return home.

Straight’s own quest to visit his brother (Harry Dean Stanton), who’s recently suffered a stroke — the two haven’t spoken in years — clearly derives from a related sentiment. In spite of his miserable health — he has encroaching emphysema, weak hips that oblige him to walk with two canes, and fading eyesight that ensures he couldn’t pass another driver’s test — he decides to make the trip on a 1966 John Deere lawn mower, towing his baggage in a cart. And he sticks to this impractical plan despite all sorts of obstacles, even after a good Samaritan (James Cada) offers to drive him the rest of the way.

Like Eraserhead — Lynch’s first and to my mind still his best feature, another religious parable with its own sense of heaven and hell — and a good many other works that might be called quintessentially American, The Straight Story is both a celebration of innocence and a deterministic confirmation of biological and familial ties. In some ways it’s a less personal work than Eraserhead because Lynch didn’t write it, and it appears that the script was developed mainly without his input. (However, two of his oldest friends have pivotal roles in the film — Jack Fisk, who helped finance Eraserhead, is the production designer, and Fisk’s wife, Sissy Spacek, plays Rose.) Nevertheless this film represents a clear desire for renewal in a career that has stalled because Lynch has relied too heavily on tropes associated with noir and sexual decadence. I hasten to add that I prefer it to Boys Don’t Cry (though director and cowriter Kimberly Peirce is clearly a talented newcomer). My preference has less to do with its ideology — I’m as susceptible as anyone to affirmative patriotic gestures — than with its artistry. Some of Lynch’s best work here periodically borders on calendar art, but overall the stylistic invention places The Straight Story on a different level.

This isn’t to say that it doesn’t have awkward and graceless moments, which seem to result from Lynch trying to prove to his fans that he’s still a weirdo with a taste for eccentricity. Two examples are a strident episode involving a woman who runs over a deer and some forced levity involving twin car mechanics, both of which disrupt what the movie is saying and doing for the sake of a few irrelevant sniggers. (By contrast, a couple of non sequiturs about Wisconsin being a “party state” are the result of a good match between Lynch’s persona and the needs of this movie.) But on the whole Lynch is smart enough to let Farnsworth dominate the proceedings and let his own stylistic pirouettes take a backseat. The only major exception is a beautifully orchestrated and mysterious camera movement around the side of a house near the beginning of the film that provides our introduction to Alvin Straight — an offscreen thud on the floor.

One of the best things in the movie is its handling of time, so that Straight’s slow progress on his lawn mower and his weeks on the road are subtly and suggestively superimposed on his entire life, which the film conveys mainly through a few privileged details in the dialogue. (An even more effective example of this kind of picaresque storytelling can be found in the latest feature of Takeshi Kitano, Kikujiro –another road movie that handles time so abstractly the action could just as well be unfolding over a week as over a year.)

Enhanced by ‘Scope framing a good deal more than Lynch’s overrated, relatively claustrophobic Blue Velvet, The Straight Story has one of the most attractive as well as one of the most sentimental forms imaginable: it’s a small story told in an epic mode. By screening out all the media hoopla that accumulated around Straight’s journey, virtually substituting stars in the sky for media stars, the movie keeps things agreeably homey — though it probably falsifies things as a consequence. By contrast, Boys Don’t Cry takes on a huge subject without abandoning small-scale observation. What either of these movies has to do with real events probably remains difficult to determine for anyone but a specialist, but as mythologies they both have plenty of staying power.