This appeared in the February 12, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Rushmore

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Wes Anderson

Written by Anderson and Owen Wilson

With Jason Schwartzman, Bill Murray, Olivia Williams, Seymour Cassel, Brian Cox, Mason Gamble, Sara Tanaka, Stephen McCole, Connie Nielsen, and Luke Wilson.

Rushmore has a good deal of content and human qualities to spare, but what makes it such a charming and satisfying experience is its style. Its segments are introduced by parting curtains, each labeled with the name of the appropriate month, which serves as a chapter heading — a neat way of calling attention to the broad and attractively composed ‘Scope frames and of parceling out the story in bite-size seasonal units. Less obvious and functional but unmistakably style-driven is the fact that the curtains come in different colors, giving another kind of lift to the proceedings. All the scenes are short (at least until the film moves into its homestretch), and director Wes Anderson also films these scenes in long and medium shots; in general he indulges in long scenes and close-ups only after he’s earned them. Because this is a studio effort that knows what it’s doing — a rare breed these days — it makes you wonder how many close-ups and long scenes are squandered in other studio releases.

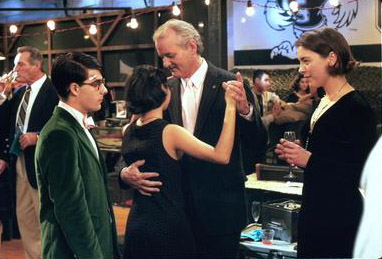

The film is a comedy about Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), a 15-year-old student at Rushmore Academy, a private school in a small town, who’s too wrapped up in a bevy of extracurricular activities — hilariously cataloged in one extended montage sequence — to finish his schoolwork. Max develops a crush on a young, widowed grammar school teacher named Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams), befriends a local millionaire and Rushmore graduate named Herman Blume, gets expelled, enrolls in public school at Grover Cleveland High, and writes and stages elaborate plays at both schools. (The first one we see him staging is derived from the 1973 movie Serpico.) He’s always a bit ridiculous, and so is Blume, but everyone in the movie is accorded a certain dignity that keeps him lovable. Significantly, the character initially introduced as Blume — played by Bill Murray at his most inspired, with a characteristic mix of quizzical distraction and terminal world-weariness — eventually becomes known to us as Herman, and even Max’s father, played with amiable sweetness by Seymour Cassel, finally registers as just plain Bert.

This dignity is often revealed in small but precious details. (To give examples, I need to recount portions of the plot, so readers may want to skip the rest of this review until they’ve seen the picture.) The bond that develops between Max and the millionaire degenerates into a protracted feud when Herman also falls in love with Rosemary after serving as go-between for his teenage pal. One of the comic grace notes in this feud involves Max’s friendship with Dirk Calloway (Mason Gamble), a much younger classmate at Rushmore, who spies Herman emerging from Rosemary’s house, blocks his car when he’s leaving, announces, “I know about you and the teacher,” and spits with fury on the hood of Herman’s car. Another comes soon afterward, after Dirk reports his findings to Max and Max arranges a meeting with Mrs. Blume to report on her husband’s infidelity; before they get down to business, Max offers her a sandwich and she accepts, choosing tuna over peanut butter. Dirk’s loyalty in spitting on Herman’s car and Max’s civility in offering the tuna sandwich are two good examples of the kind of gifts offered by this movie to both its characters and its viewers — an act of piety toward passion in the first case, a respect for simple courtesy in the second.

Comparable gifts crop up in almost every scene. Some involve Max’s father, whose doting and nonjudgmental affection is undiminished by either Max’s horrible grades or his defensive claims to Herman and his wealthier Rushmore classmates that his barber father is a neurosurgeon. Some involve Rosemary’s gentle negotiation of Max’s infatuation and her own guarded affection for him; some involve the fluctuating friendship between Max and Herman; and still others relate to Max’s shifting relationships with Dirk, with his worst enemy at Rushmore — a Scottish bully named Magnus who’s much older, played by Stephen McCole — and with Margaret Yang (Sara Tanaka), a classmate at Grover Cleveland who likes him in spite of everything.

Adolescence is a big comic subject in American movies, but it’s usually squandered — along with close-ups and longer scenes — with strident acting and other telegraphed effects. But Anderson, who wrote Rushmore with Owen Wilson, never allows the audience to lose its dignity either; the coolness of the comedy — like that of Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati, and Albert Brooks — respects us and characters alike. The pain and cruelty of adolescence aren’t avoided, but the short-scene construction and gliding tempo prevent us from dwelling on them; the calm objectivity of a Keaton, Tati, or Brooks gazing at the world qualifies as a kind of measured wisdom, and Rushmore emulates this sane equipoise throughout.

Treating quirky adolescents with affection was already central in Bottle Rocket, Anderson and Wilson’s only previous feature (in which Wilson played one of the leading parts), but for all that movie’s style and grace, it bears the same relationship to Rushmore that a watercolor bears to an oil painting. This movie goes further by creating something more than a milieu and a circle of friends, widening its span to encompass a little world to contain them. It also dissolves the usual distances between characters of various ages (including not only Dirk and Magnus in relation to Max, but also Herman and to some extent Rosemary), creating a utopian democracy of concerns that purposefully rejects the automatic and often unconvincing generational solidarity that underlies most movies about teenagers. This is perhaps the movie’s most inspired wild card, though it also means that the world of the film begins at times to become infused with magical realism. Even if we accept Max’s becoming best friends with Herman, the disaffected father of two of Max’s classmates, we may balk when Max subsequently persuades Herman to spend eight of his ten million dollars on an aquarium designed to win Rosemary’s admiration. At this stage the film’s comic invention gets stuck in a groove; the adolescent grandiosity of both Max and Herman expands only because it has nowhere else to go, warping the world that contains them in the process.

These occasions aren’t the movie’s finest moments; they indicate that the filmmakers became so smitten with their characters that they got carried away, much as the characters themselves get carried away with their infatuations. Yet even this flaw is seductive — as it is in the fiction of J.D. Salinger, another sympathetic chronicler of adolescent overreaching whose eagerness and attentiveness can lead his fiction into equivalent forms of fantasy projection and hyperbole. To their credit, Anderson and Wilson share none of the class snobbery that subtly infuses much of Salinger’s work, and though they don’t harp on it, they seem to understand some of the less articulate forms of adolescent anguish that arguably make Booth Tarkington’s Seventeen an even better evocation of teenage nightmare than The Catcher in the Rye. But like Salinger they harbor a protective gallantry toward their characters that becomes the film’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness.

For all its lightheartedness, Rushmore reeks of mortality and historical trauma — a paradox made possible by its stylistic fleetness, pumped along by snatches of nearly a dozen British pop tunes of the 60s. (Anderson’s nostalgic and lyrical employments of this music often recall the more extended uses of Simon and Garfunkel in The Graduate, a quintessential pop expression of the 60s.) Max’s dead mother, Rosemary’s dead husband (another Rushmore graduate), and Herman’s stint in Vietnam may not be equivalent points of reference for these characters, but the movie gently treats them as if they were. (The movie never really furnishes an explanation for Herman’s boredom and alienation, apart from his wealth and his conventional jock sons; Vietnam is Max’s hypothesis for the root of Herman’s problems, and by default it becomes the movie’s as well.) Max’s climactic and hilarious play about Vietnam — staged at Grover Cleveland with elaborate special effects in the movie’s final and longest sequence — is dedicated to his mother and to Rosemary’s late husband (“the friend of a friend”), pointedly bringing all three together. It’s Anderson’s way of hinting that all three characters have suffered irreparable losses without hitting us over the head with them, and it seals the past’s ongoing claims on the present that locate the entire movie in some kind of temporal netherworld that is neither. (The traditionalism of the school itself, so central to Max’s sense of his own identity, is clearly part of this period ambiguity, along with the importance of Watergate, Serpico, and Vietnam to Max’s career as a playwright.)

The play itself is about reconciliation; it ends with Max, playing an American grunt, proposing to a Vietcong guerrilla played by Margaret Yang, his new girlfriend. It also leads to other reconciliations: between Max and Magnus, Rosemary and Herman, Max and Rosemary. There’s even a reconciliation between Max and Rosemary’s friend from Harvard, a young man whom Max drunkenly castigated as an interloper at a dinner after the premiere of his previous play. Unlike the madder schemes of Max and Herman, this optimistic ending bears some recognizable relation to the real world: not only has the past become integrated with the present, but the invented world of Rushmore has become wide enough to encompass our own.