From the Chicago Reader (July 10, 1998). One thing that has recently led me to reconsider my estimation of Aki Kaurismaki is this superb, engaging appreciation of him by Girish Shambu.– J.R

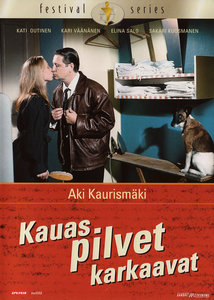

Drifting Clouds

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Aki Kaurismaki

With Kati Outinen, Kari Vaananen, Elina Salo, Sakari Kuosmanen, Markku Peltola, and Matti Onnismaa.

It might be risky to generalize about national character after visiting a country for only a week, but the particular kind of self-deprecating humor in all six features I’ve seen by Aki Kaurismaki was equally apparent during my recent visits to both Helsinki and the Midnight Sun film festival in Sodankyla. Kaurismaki and his older brother Mika, also a filmmaker, are the founders and guiding spirits of this festival, and its artistic director is one of their best friends, so the humor I’m describing is probably a type that flourishes under their eccentric auspices.

Roughly speaking, this attitude derives in part from the belief that Finns are perceived as the Poles of Scandinavia. Their language shares more roots with Hungarian and Estonian than with Swedish, Danish, or Norwegian, and Helsinki, by virtue of being only a few hours from Saint Petersburg, may have more links with Russia than with its Nordic cousins. Since Scandinavia itself is already regarded as a remote neck of the woods, the Kaurismakian concept of Finnish urbanity involves an embrace of drabness and hillbilly traits relished more for their earthy pathos than for their cosmopolitan aspirations. The purest form of this Li’l Abner humor can probably be found in the studied incongruity of Kaurismaki’s three “Leningrad Cowboys” movies, only the first of which I’ve seen (Leningrad Cowboys Go America, 1989). This humor must strike some chord in the general populace: a few summers back, a massive outdoor screening in Helsinki paired Leningrad Cowboys Meet Moses (1994) with The Ten Commandments (1956).

Given the overall sophistication and success of the Kaurismaki circle as a local cultural force — the brothers, who spend much of their time living and working abroad, currently run a first-rate restaurant inside Helsinki’s brand-new Museum of Modern Art and an ambitious art-cinema complex flanked by a deliberately tacky dive known as the Moscow Bar — their cultivation of clodhopper humor has to be seen as an ironic pose; yet it’s also grounded in an authentic desire to honor their roots. This helps to explain why, when Mika’s wife, filmmaker Pia Tikka, served me and a few other foreign guests sandwiches from the Moscow Bar’s counter, she apologized for them being fresh rather than stale and greasy, as they were generally supposed to be. (In the same jovial spirit, the festival director told me that if I wanted to come back next year he would have failed in his mission.)

The Moscow Bar is itself an improbable tribute to what’s left of communist culture in Finland. The same could be said of Drifting Clouds (1996) — Aki Kaurismaki’s most recent feature, playing this weekend at the Film Center — and not only because the Moscow Bar briefly appears as one of the places where the heroine, Ilona (Kati Outinen), searches for a job. Though it has a happy ending, the film is about the sorrows of unemployment, which automatically gives it more universality than the explosion-packed thrillers that fill most theaters. On the other hand, proletarian humanism, like communism and everyday experience, isn’t a very fashionable commodity these days, so cloaking it in irony is the best way of getting it into art theaters. And dressing it in minimalist, color-coded locations (most of the film is designed in dreamy and decorous shades of blue) makes it even more palatable.

What can be said about Drifting Clouds can be said about hangdog Finnish humor in general: it’s making the best of a depressing situation. Some people blame the melancholia and alcoholic giddiness found in this country on the weeks of darkness in the winter and the weeks of daylight in the summer. (Coincidentally, the psychological effects of the midnight sun are alluded to more directly in the Norwegian police procedural Insomnia, a less interesting film playing this week at the Music Box.) Whatever the source, these phenomena create an ambiguous emotional texture in which the tenderness of Finnish tangos and the brutality of drunken rages can seem like reverse sides of the same coin, and where camp attitudes seem to operate as safety valves for both extremes.

Writing in the English film magazine Sight and Sound about a year ago, critic Jonathan Romney singled out an early, self-referential moment in Drifting Clouds as emblematic of the emotional ambiguity of Kaurismaki’s deadpan comedy. Shortly after losing his job as a streetcar driver, Ilona’s husband Lauri (Kari Vaananen) stomps out of a cinema with his wife, declaring, “Unbelievable rubbish! It’s supposed to be a comedy and I didn’t laugh once.” He demands his money back from the cashier; when the cashier reminds him that he didn’t pay for his ticket in the first place, Lauri asks for his dog back instead, and the couple’s equally impassive terrier is dutifully passed across the counter. Outside the cinema Ilona gently tells her husband that she thought the picture was good and that he shouldn’t have been so mean to the cashier — who is, after all, his sister. “So much the worse for her,” Lauri concludes.

This is Kaurismaki’s cinema in a nutshell — especially because, as Romney points out, some people walk out of his movies uncertain of whether they’ve been watching a comedy and because “frustration and self-disappointment” are at the roots of his self-deprecating humor. The tenderness of wife, dog, and sister and the unreasoning rage of Lauri fit together like hand in glove, yet despite the scene’s superficial likeness to the sadomasochistic charades of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the tenderness dominates: what typically registers as bittersweet in Fassbinder is mainly sweet here, in spite of the bitterness. Significantly, Kaurismaki’s definition of “what makes a director immoral” is “unneeded violence,” adding, “I don’t think Hollywood has any morality. They’re spoiling our children with the shit they’re producing.”

When Drifting Clouds opens, Ilona is headwaiter at the Dubrovnik restaurant in Helsinki, which is frequented by elderly couples and offers live music for dancing (mainly Finnish tangos). Her competence and pride in her work are apparent in the opening scene, when she manages to wrest a carving knife away from the alcoholic chef (Markku Peltola), while the kitchen staff cowers in terror, and subsequently dresses the wound of the doorman, Melartin (Sakari Kuosmanen), who’d failed to disarm him. After work she joins her husband on his streetcar, and when they enter their flat he surprises her with his latest purchase — a color TV bought on an installment plan. She’s more of a realist than he is and wonders at his wisdom: they’re already making payments on their sofa and bookshelf, the latter purchased before they could afford more than a handful of books.

The next day Lauri discovers that the streetcar company is getting downsized and he’ll be losing his job in a month’s time, but a month goes by before he tells Ilona the bad news. (He’s every bit as prideful as she, though less practical and more prone to drink away his worries.) Not long after Lauri starts looking for another job, Ilona discovers from her boss (Elina Salo) that the bank extending loans to the Dubrovnik is repossessing the restaurant, selling it, and letting everyone go.

Thus begins a long chain of worries for both Ilona and Lauri as they look separately for work, hindered by corruption and exploitation along the way (a thug who runs a snack bar hires Ilona but fails to report this to the tax authorities). An additional sadness hangs over the proceedings because the movie was originally conceived for actor Matti Pellonpaa, a Kaurismaki regular who essentially drank himself to death before the film went into production. The film is dedicated to his memory, and as a more private memorial a childhood photograph of him appears, presented as a photo of Ilona and Lauri’s deceased son.

Kaurismaki has said that Drifting Clouds is bound at one end by the grief of The Bicycle Thief and at the other by the joy of It’s a Wonderful Life, with “the Finnish reality” somewhere in between. It’s another way of outlining the difficult synthesis produced by Finnish tangos and enormous quantities of vodka, endless summer days and endless winter nights.