This appeared in the March 20, 1998 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Michael Paxton

Narrated by Sharon Gless.

Primary Colors

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Mike Nichols

Written by Elaine May

With John Travolta, Emma Thompson, Adrian Lester, Kathy Bates, Billy Bob Thornton, Larry Hagman, and Maura Tierney.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Two highly partisan political movies are opening this week, a right-wing independent documentary and a left-wing Hollywood feature — though it’s not clear that the filmmakers of either would categorize their work in this way. Certainly it wouldn’t be any exaggeration to call both films the efforts of special interest groups — a movie about Bill Clinton put together by people who mainly qualify as his supporters and friends and a sincere hagiography of novelist and philosopher Ayn Rand fashioned by many of her disciples and acolytes. How far they actually carry their respective loyalties is a different matter, however. Ultimately both movies flounder as well as triumph because of their insider points of view, though not always for the same reasons.

Whenever Ayn Rand’s name comes up, I have an impulse to scoff, an impulse I think is shared by many others. To its credit, Michael Paxton’s Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life — which I’m tempted to call “Ayn Rand: A Sense of Camp” — acknowledges this snobbish impulse more than once. But to its discredit it attributes people’s skepticism about Rand almost exclusively to the culture’s supposed ideology of collectivism, without taking other factors into account.

Rand’s taste in literature and the other arts is an obstacle when it comes to accepting her as a world-class intellectual, as this film clearly does: she revered others besides Aristotle, Victor Hugo, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Fritz Lang of Siegfried and Metropolis. Paxton’s film alludes to Rand’s touching celebration of the utopian spirit of Marilyn Monroe, offered shortly after the actress’s death, but it excludes her appalling defense of the early novels of Mickey Spillane and his hero Mike Hammer as models worthy of emulation. (Spillane eventually became Rand’s friend, and she wrote with admiration in The Romantic Manifesto that “he gives me the feeling of hearing a military band in a public park” — one indication of her musical taste, which mainly ran to what she called “tiddlywink music” from the turn of the century.) Page through the index of the recently published Letters of Ayn Rand in search of the giants of literary modernism, and you find most of them are absent — although she does link James Joyce to the “beatniks” as an example of the sort of junk that’s “admired in English courses.” And Gertrude Stein? “She is being published, discussed and given more publicity than any real writer. Why? There’s no financial profit in it. Just as a joke? I don’t think so. It is done — in the main probably quite subconsciously to destroy the mind in literature.” Whose, one wonders?

But such criticism is secondary. Part of my reflexive scoffing at Rand is intellectual and part is political; but a third part is emotional. I suspect that this part is closely allied with the reasons that many Americans scoff at Jerry Lewis: like Rand, he’s come to stand for a stage in our adolescence that we’d rather forget. Rand’s vibrant appeal to adolescents, including me when I was in high school, is profoundly sexual: she provokes a sense of exalted fantasy tied up with raging hormones and resolves the vexing need to reconcile self-interest with social and ethical duties. Rand’s message that selfishness is empowering and self-sacrifice is destructive can cut through teenage confusion like a piercing yet comforting ray of light, as penetrating as Rand’s own gaze, and make one’s blood race in the bargain.

Indeed, the sexiness of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged is an integral part of their utopianism, making them blood sisters of Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will and Olympia in their kitschy splendor and sexual lift (if not in their political programs). “It seems that erotic verve is indissociable from contempt for all community, from frantic exaltation of individuality in the furtherance of traditional social and moral principles,” Luc Moullet wrote in Cahiers du Cinéma in 1958, citing Jet Pilot and The Fountainhead as the two summits of right-wing eroticism.

We tend to avoid this brutal fact, but the American dream of untrammeled freedom and glittering self-realization can at times be boiled down to a compulsive desire to relive and rewrite our adolescent traumas, giving them a happier outcome. If Jerry Lewis represents the implied hell of adolescence, Ayn Rand ushers us into the implied heaven, for which her phallic skyscrapers are always reaching. In some ways this makes her as threatening to adult minds as she is attractive to adolescents. Moreover, since Rand herself fled communist Russia to script Hollywood movies when she was 21, surely her own American adventure was a protracted postadolescent episode, for better and for worse.

Paxton is certainly attentive to the romantic side of Rand’s legacy, but he skimps on the sexual side. For that story, one needs to turn to Barbara Branden’s fascinating and troubling 1986 biography, The Passion of Ayn Rand (subsequently made into a movie), which offers a compendium of the kind of material that Paxton can’t begin to handle. This stretches all the way from a Petrograd friend named Leo (a traumatic infatuation that he didn’t reciprocate) to Nathaniel Branden, the biographer’s former husband and Rand’s designated intellectual heir and key acolyte for the better part of two decades. For 14 of those years — beginning in the mid-50s, when he was 24 and Rand was pushing 50 — they were lovers, with the full knowledge and tortured approval of their spouses but almost no one else within their tight, intensely interactive circle. Their affair came to a cataclysmic end when Rand discovered that Nathaniel had been sleeping with another Rand acolyte for several years. He was violently and totally excommunicated — an action accounted for publicly only by Rand’s announcement that he’d been involved in a series of personal and professional deceptions.

Significantly, Leo isn’t mentioned at all in this purportedly intimate documentary, and Nathaniel is accorded a stretch of about three and a half minutes (out of 145). Meanwhile brave Barbara Branden — who remained a passionate Rand disciple before, during, and after Rand’s affair with her husband and one of Rand’s closest friends until shortly after his excommunication — barely figures at all. (The complex spiritual links between Ayn, Nathaniel, and Barbara are perhaps rooted in the fact that they all adopted hard-sounding goy replacements for their original Jewish names: Alice Rosenbaum, Nathaniel Blumenthal, and Barbara Weidman. Neal Gabler’s provocative thesis in An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood — that Hollywood’s version of the American Dream was largely the dopey creation of Jews in flight from their ethnicity — can probably be applied equally well to the founding gospel of Rand’s Objectivism, which was in turn guided by Hollywood, as this documentary cogently shows.)

Given Rand’s monstrous behavior when she unleashed the fury of a woman scorned, it’s understandable that Paxton leapfrogs over this pivotal episode and omits the painful story of Leo. But the crushing irony of Paxton’s massive act of repression — made in deference to Rand and her own self-representations after her bitter break with the Brandens — is how close it comes to the historical elisions of Stalinism. This is a paradox to reckon with, because it’s difficult to think of a 20th-century writer who hated communism in general and Stalinism in particular more than Rand did. But even if this movie dutifully, eloquently articulates that hatred while it simultaneously (and probably unconsciously) enacts a Freudian return of the repressed, the history of the cold war was full of such unnerving mirror effects — like the ideological boomerang that turned this country and the Soviet Union into grotesque twins at the height of their mutual opposition.

In spite of all my objections to Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life, I have to admit that I found it compulsively watchable — partly because Paxton is so adept at lacing Rand’s arguments with their fantasy inspirations (which in the documentary range from vintage film clips to original animation interludes, with lots of Hollywood gossip in between) and partly because Rand is still a deeply affecting figure. For all her championing of unlimited laissez-faire capitalism, she refused the label of conservative — considering American conservatives even worse than American liberals — preferring the designation “radical capitalist.” True, she was stupid enough to declare to the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947 that the Russian people never smile — “If they do, it is privately and accidentally. Certainly, it is not social” — a fact tactfully omitted in the documentary. But she was also sensible enough to consider these hearings a pathetic farce — a fact that the documentary includes.

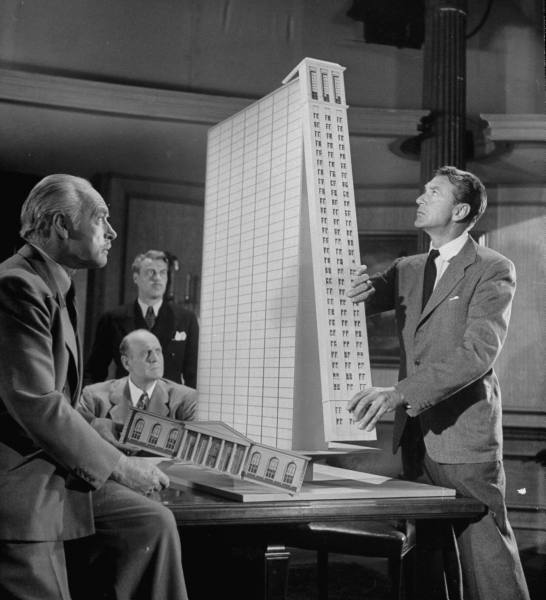

One might assume that she would have welcomed Ronald Reagan and his economic reforms with open arms — particularly after one of her disciples, Alan Greenspan, became a top Reagan adviser. But as she wrote to a fan in 1981, “I did not vote for any of the Presidential candidates. I do not approve of Mr. Reagan’s mixture of capitalism and religion.” (In a warm letter to Barry Goldwater almost two decades earlier, she wrote of the National Review, “I am profoundly opposed to it — not because it is a religious magazine but because it pretends that it is not.”) Because her atheism ran neck and neck with her economics, she refused to condone potential boondoggles and convenient alliances. (That same inflexibility could be found in some of her heroes; informed gossip tells me that the reason Frank Lloyd Wright set impossible conditions for designing the sets for the film version of The Fountainhead was that he regarded Rand as something of a screwball.) In fact, the only political campaigning she ever did was for Wendell Willkie in 1940, and she became so disillusioned by what she regarded as his betrayal of capitalism in his speeches that she wound up declaring him “the guiltiest man of any for destroying America, more guilty than Roosevelt, who was only the creature of his time, riding the current.” (Betrayals were as vital to her erotic program as projected matches on Mount Olympus.)

Rand’s inability to compromise undoubtedly produced a kind of tragic heroism, and Paxton’s affectionate portrait amply illustrates her unswerving idealism. After the death of her beloved husband, Frank O’Connor, in her later years, she was asked on a national TV show if she wouldn’t entertain the possibility of joining him in an afterlife. Her poised and firm reply was that if she could, she would kill herself immediately. One of the film’s final quotations from her is for me the most memorable, encapsulating her art and her metaphysics in a single phrase: “Death isn’t important; eternity is important, and eternity is now.”

The testing of idealism is the key subject of Primary Colors as well, played out in various convergences of politics and sex. But the most important idealism being tested isn’t that of Bill Clinton — called Governor Jack Stanton in the movie, and very amiably played by John Travolta. It’s that of Henry Burton (Adrian Lester), a young black political strategist who decides to go to work for Stanton in the opening sequence. Henry’s less compromising black-activist girlfriend — played by real-life activist Rebecca Walker — dumps him in disgust early on because of this decision, which is the signal to hard-core radicals in the audience to take their leave as well. Whatever else it may or may not be, Primary Colors is first and last a mainstream Hollywood entertainment, a Mike Nichols movie — not an Elaine May movie, even though she’s credited with the script. And that means that viewers looking for engagement with political issues are bound to be disappointed.

With one exception, however: the issue of Henry’s idealism. How far is one prepared to support a sincere populist liberal willing to sell himself, his opponent, and his electorate down the river in order to win? And this is where the movie becomes somewhat Brechtian, because rather than answer the question, it asks viewers to arrive at their own conclusions. Jack Stanton may be charismatic and sincere — the genuine article, as Henry plainly believes. But many of the things Stanton and others do in the name of his charisma and sincerity, and supposedly for the sake of their continuance, are fairly repulsive. One causes Henry to stop by the side of a country road and throw up, and another leads a member of Stanton’s treasured team to commit suicide; a rival politician’s career is almost destroyed, and the fact that this act is averted doesn’t rule out the possibility that it might have happened — and might still happen. The image that opens and closes Primary Colors is of a waving American flag and a white hand shaking a black one; the opening offscreen commentary is an analysis of the nuances of Stanton’s handshakes — the meaning of what his right and left hands are doing — but the closing offscreen commentary, presumably about the same subject, is assigned to the audience. (If you believe Time magazine, however — and bear in mind that a few months ago it declared Titanic “dead in the water” and a probable box office disaster — the ending has no such ambiguity or open-endedness, expressing Henry’s full support of Stanton.)

Sex comes into the picture because glad-hander Stanton can’t keep his hands off his female constituents. (It’s implied that his hands-on manner is the flip side of his overflowing social conscience.) One of my colleagues has called this picture “Clinton’s Mount Rushmore.” But if that’s what it is, surely those craggy features wind up casting a lot of dark shadows; rather than imply that this character is our rock and our salvation, Primary Colors more sensibly suggests that this man is merely what we’ve got to work with.

I liked Primary Colors and am prepared to defend it, though I must admit that the film’s luster has started to fade a little, four days after I saw it. I’ll have to see the movie again to determine whether the fault is mine or Nichols’s. Although it’s refreshing to find in a Hollywood movie that the main audience identification figure is a black man and the principal moral spokesperson is an overweight lesbian (nicely played by Kathy Bates), the filmmakers are still too far inside the media mentality they’re trying to describe to come up with many fresh insights about Clinton. Though Stanton isn’t viewed as a man without flaws — he’s certainly more fully rounded than Rand in Paxton’s documentary — the overall spirit of the portrait remains closer to roast than critique. What is much more seriously critiqued is the kind of spin control Stanton practices and provokes. But even here, most of his more questionable actions occur offscreen and are reported to Henry in a series of dispatches. (The filmmakers’ decision to keep Stanton’s sexual activities offscreen can also be linked to a related, more defensible strategy — privileging Henry’s viewpoint as the conduit of our own moral judgment.)

Part of the problem with making a movie as “newsworthy” as this one is that the news itself is likely to inflect our perception of the work: we’ll perceive its flaws and virtues independently of the filmmakers’ intent. If amiable Bill had decided back in February to sacrifice the lives of thousands more innocent Iraqis (and a few more Americans as well) in a second conflagration for the sake of “standing up to Saddam” or selling a few more weapons, Stanton’s caring nature — which doesn’t necessarily extend to non-Americans — might have looked a lot less meaningful. The fact that Clinton’s currently being hounded for presumed sexual escapades, which seem to matter more to newscasters and political opponents than to anyone else, makes Stanton seem more vulnerable and beleaguered than he might have otherwise. But our sympathy has nothing to do with his political performance, which exists outside the realm of the movie’s discourse — as does Clinton’s political performance, for that matter.

It’s always been this way. Without presuming to comment on presidents in office, Advise and Consent (1962) and The Best Man (1964) pretended to deal with the issues of Washington politics but were actually concerned almost exclusively with public relations; the same is true of Primary Colors. Since the film equates the heady excitement and near disasters of putting on a show with the perils and rewards of a presidential campaign, Primary Colors at times resembles The Band Wagon. What’s said about most of the political decisions adds up to nothing more than window dressing. The same observation applies, of course, to our presidential campaigns themselves; people were equating politics and show biz long before Primary Colors was a mere gleam in the eye of Joe Klein, who published the original novel anonymously.

I’ve only had a chance to skim this work, but it’s clear that May’s adaptation follows it fairly closely, right up to the ambiguous ending. Though I assumed that the hilarious “Schmooze for Jews” radio broadcast in the movie, hosted by Rob Reiner, must have been her invention, it turns out that she only added a few comic inflections to a scene from the novel. Especially considering that the film originally included a one-night stand between Henry and Mrs. Stanton, which was in the novel but cut from the movie when it tested badly, this may be an adaptation that, for all its hipness and intelligence, is faithful to a fault, more faithful than the original deserves.

One of the hazards of a roman à clef is that identifying the characters’ real-life equivalents may divert the audience’s attention from the story’s broader concerns. The movie does caricature various members of Clinton’s inner circle, ranging from Billy Bob Thornton’s dead-on version of James Carville to Emma Thompson’s much more uneven impersonation of Hillary: she adroitly captures certain behavioral tics but isn’t very convincing when it comes to the first lady’s inner life, from her political passion to her responses to marital infidelity. (Thompson could also be hampered by the screenplay: when May isn’t simply scoring satiric points, she usually writes better dialogue for men than for women.)

But despite my reservations about individual characterizations, there’s an undeniable excitement in finding real-life characters transposed into a movie and being asked to reconsider them in movie terms — a process that both formalizes what the media already does to them and alters the media representation by having real-life characters interact with others who are more clearly fictional. Many of these may also have some limited basis in reality, but not enough to allow us to judge them as if they had clear counterparts. Henry, for instance, is said to be derived from George Stephanopoulos, and Kathy Bates’s Libby has been linked to Betsey Wright. But the differences are often so huge that the movie’s characters can’t be read coherently as portraits of real-life individuals. The candidates running against Stanton are even less recognizable, except as unwieldy composites.

The film’s approach has the potential for many forms of confusion, but it also opens up the fruitful possibility of evaluating a few public figures (Bill and Hillary, James Carville) in a more coherent and thoughtful way than is generally allowed for by TV news, seeing them function in a few hypothetical moral situations rather than merely shunted through photo ops and TV interviews. But the bottom line of this movie’s ethical inquiry has to do with our reactions to Henry, not the media stars — because he has a relation to the Clintons within hailing distance of our own.

Paradoxically, if the movie functions in the Brechtian fashion I’ve been outlining, it’s Henry and not Bill Clinton who registers as real, because Henry embodies some of our own decisions when it comes to Clinton. In contrast to Henry, Clinton and Stanton are mysterious, unknowable postulates derived from media traces — fictional constructs that are at best based on some version of the truth offered by an often unreliable press. We may think we know Stanton a little better than we know Clinton because Klein, Nichols, and May offer us a few “candid” glimpses from closer range than the media are usually allowed. But this is still a game of smoke and mirrors — a magic show in which Clinton, Travolta, Klein, Nichols, and May are the magicians and we’re the audience members waiting to be persuaded. Henry, on the other hand, is one of us — an audience member who’s been offered a few behind-the-scenes disclosures and returns to tell us what he’s seen. What do we say to him in response?

Of course I’ve oversimplified matters by describing Henry as our representative: after all, his first act is to join the magicians, becoming a spin doctor himself. That’s the irresolvable paradox of any movie that purports to offer outsiders an insider’s look. But at least this very entertaining movie makes us ask a few questions about how we get fooled — and how far we’re prepared to go with someone who keeps on fooling us.