From the June 6, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

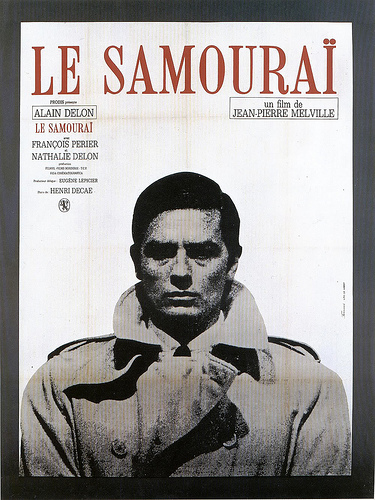

Le samourai Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Jean-Pierre Melville

With Alain Delon, Francois Perier, Nathalie Delon, Caty Rosier, Jacques Leroy, Jean-Pierre Posier, and Catherine Jourdan.

The Birth of Love Rating *** A must see

Directed by Philippe Garrel

Written by Garrel, Marc Cholodenko, and Muriel Cerf

With Lou Castel, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Johanna Ter Steege, Dominique Reymond, and Marie-Paule Laval.

If much of French cinema can be said to derive from the famous Cartesian phrase “I think, therefore I am,” why does it yield so many realistic movies? Certainly fantasy remains central to a good deal of French art, past and present, but if you compare the films of early pioneers like the Lumiere brothers to those of Thomas Edison, you might conclude that the French have a certain edge in seeing clearly what’s right in front of them. I found that of the dozen French movies I recently saw in Cannes and Paris, six were strictly realist in a way that few American features are: a cheerful Pagnolian hand-me-down (Marius and Jeannette), a Blier road movie for grown-ups (Manuel Poirier’s Western), Manoel de Oliveira’s moving French-Portuguese self-portrait, which features Marcello Mastroianni’s last performance (Voyage to the Beginning of the World), an experiment in first-person camera involving adultery (La femme defendue), a mysterious meditation on rural French punks (deceptively titled The Life of Jesus), and a spirited comedy by and with Brigitte Rouan (Post-coitum, animal triste). Four offered alluring mixtures of realism and fantasy: two episodes of Jean-Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinema, an untitled short by Leos Carax (who, like Godard, mixes real history with heady speculation by using clips), and Anne-Marie Mieville’s provocative three-part head scratcher We Are All Still Here, with Godard in remarkable performances in the last two parts. Only two films were pure fantasies: Mathieu Kassovitz’s muddled Scorsese and Stone rip-off Assassin(s), which purports to be realistic, and Raul Ruiz’s Genealogies of a Crime, an affectionate satire of psychoanalysis smart enough not to claim anything of the sort.

Maybe realist movies provide a necessary antidote to French culture’s dedication to the life of the mind — offering a kind of periodic wake-up call. For a good idea of French cinema at its most and least realistic, you should check out Philippe Garrel’s hyperrealistic 1993 The Birth of Love, playing this week at Facets Multimedia, and Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1967 fantasy Le samourai, playing this week at the Music Box. Both were made by fierce, intransigent independents, and together they represent a sort of yin and yang of French cinema.

The two couldn’t be further apart in their depictions of intimacy — one of the things that realism endeavors to be real about. The younger Garrel, a self-proclaimed spiritual son of Godard (who did virtually adopt him in May ’68, when both were cruising the Latin Quarter student demonstrations with their cameras), is a master at dealing with intimate moments between lovers, friends, and family members, yet he’s willfully indifferent when it comes to connecting these moments into a story. Melville, who died in 1973 and who’s a spiritual heir of Godard (who cast him as a memorable sage-in-residence in Breathless), is a master storyteller who founders in Le samourai when he has to convey any kind of intimacy at all.

Both filmmakers are consummate visual stylists. The Birth of Love, shot in black and white by Raoul Coutard (the cinematographer on most of Godard’s early features), is so beautifully modulated in its high-contrast palette of tones that black and white become almost a kind of color. Le samourai, shot in color by Henri Decae (another New Wave luminary who shot The 400 Blows, Purple Noon, and the early features of Claude Chabrol), is so exquisitely controlled in its narrow palette — finding something that’s metallic blue-gray in almost every shot — that, as Melville expressed it himself, it presents color as a kind of black and white.

Born Jean-Pierre Grumbach, Melville changed his name in homage to one of his three favorite writers as an adolescent (the other two were Poe and Jack London); the same sort of Americanophilia marked his early filmgoing in the 30s and 40s. Long before Cahiers du Cinema was even a gleam in the eye of its founders, Melville worshiped at the shrine of Hollywood and dutifully cataloged its artistic riches. In his book-length interview with Rui Nogueira, he proudly recites a carefully composed list of 63 prewar American directors of the sound period, all of whom made at least one film that he loved. (The three controversial omissions from the list were Charlie Chaplin, Cecil B. De Mille, and Raoul Walsh — the first “because he is God, and therefore beyond classification,” as Melville put it, and the other two because Melville disliked their prewar work.) Later Melville came to be identified personally by his Texas-style Stetson and dark glasses (the latter adopted by Godard himself) and cinematically by his loving appropriations of other macho Hollywood emblems: plot elements from The Asphalt Jungle in Bob le flambeur (1956), the police headquarters from City Streets in Le doulos (1963), and, most remarkable of all, the precise look of a cheesy 50s Columbia Pictures noir in Le deuxieme souffle (1966), his first major commercial success. As Dave Kehr observed in this paper 15 years ago, “Melville made his most personal films by imitating the most regimented, industrial era in American filmmaking — a paradox that must have appealed to the paradoxically minded Godard.” Melville embarked on professional filmmaking after the Second World War, when he was in his late 20s — making his impressive first feature, Le silence de la mer (1947), illegally after the French film union rejected his application to make a picture (later he had to pay a hefty fine); eventually he built his own studio, just as his god Chaplin did. (Tragically, this facility was gutted by a fire in 1967, not long after Le samourai was made.) Starting out as an accomplished writer-director of art films — the best known of which is Les enfants terribles (1949), a lyrical and dreamlike adaptation of Jean Cocteau’s novel — he gradually gravitated toward the sort of noir thriller that he’s mainly identified with today, switching to color only when commercial considerations made it obligatory (Le samourai is only his second color film.)

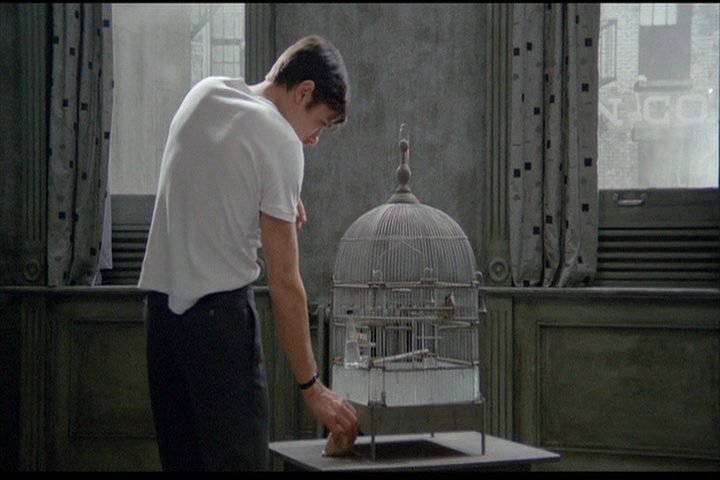

Clearly the adolescent, homoerotic side of Melville’s Cartesian stoicism and his passionate aestheticism together turned him into a mannerist, and Le samourai into a piece of holy writ for critic Tom Milne (the most sensitive of Melville’s exegetes) and more recently for filmmakers Quentin Tarantino and John Woo (two other heterosexual directors specializing in homoeroticism). A semimystical tale about a lonely hit man (Alain Delon) inhabiting a one-room hovel where even the blue packages of Gitanes, the labels on the Evian bottles, and the gray bullfinch that is his sole companion are color coded with the drab surroundings, Le samourai opens solemnly with a “quote” from The Book of Bushido: “There is no greater solitude than that of samurai, unless perhaps it be that of the tiger in the jungle.” Melville later acknowledged he’d invented the saying out of whole cloth. The plot is reportedly derived from a novel, but it’s easy to imagine he invented everything else in the film as well.

Jeff Costello (or Jef, as the subtitles have it) is neither a tiger nor a samurai but a poker-faced beefcake icon — the young Delon posited as a sacred love object — whose solitude and love relationships are so artificially and abstractly delineated that they seem part of the decor, like the cigarettes, mineral water, and chirping bullfinch. (For true pictures of solitude and the genuinely suicidal character — which are rarely found in films — see whenever you can the best movie I caught in Cannes, Abbas Kiarostami’s beautiful, spiritual The Taste of Cherry, which makes total mincemeat of a fantasy like Melville’s.) Le samourai expresses a kind of loneliness to be sure, but it’s that of a teenage male dreaming about Hollywood movies and their accoutrements — penthouse apartments, acerbic cops, melancholy city streets, smoky card games, fancy jazz nightclubs — which he projects into a Paris of the mind. Beginning with almost no dialogue at all, Le samourai unfolds like a poetic fever dream. Once the color coding relaxes a little — and Costello is pursued through the Paris metro by various plainclothes cops monitored by a head detective (Francois Perier) with a giant map — the movie becomes another kind of charming fantasy of arrested development, little boys playing with their model trains. But because the characters remain so wispy, at no point does the film break through to the kind of existential toughness and despair it claims for itself.

Melville himself labeled Costello a schizophrenic, but to believe in his diagnosis — or in the reality of the two characters who give Costello an alibi for the murder he commits, his girlfriend (Nathalie Delon) and a chic jazz pianist (Caty Rosier) who actually witnessed the killing — one has to accept the character mythically and abstractly, not as any sort of psychological or spiritual entity. The pianist, a black angel of death derived from Cocteau’s Orphee, is as insubstantial as the girlfriend when it comes to motivation, but at least she has the poetry of fairy tales to support her. The girlfriend — played by Delon’s wife at the time — is merely a useful piece of furniture to be wheeled on-screen whenever needed. Neither character can be said to interact with Costello in any way except iconographically; Melville can only cut away sheepishly from intimate moments between both couples, asking us to fill in the ill-defined blanks.

Garrel has spent his whole career defining and filling in blanks of this kind; it’s the context surrounding the blanks that gives him — and us — trouble. This is a problem shared in one way or another by at least four other major figures who might be called Garrel’s artistic cousins: Chantal Akerman, John Cassavetes, Jean Eustache, and Maurice Pialat. Significantly, all five filmmakers are central figures for a generation of highly talented and knowledgeable critics born around 1960: Adrian Martin in Australia, Nicole Brenez in France, Alexander Horwath in Austria, and, in the United States, Kent Jones (whose lovely essay about Garrel, “Sad and Proud of It,” can be found in the May-June issue of Film Comment). The fact that each of these critics acquired his or her interest in these filmmakers (and in Monte Hellman and Abel Ferrara) before becoming acquainted with any of the other critics of the same persuasion suggests the glimmerings of an intriguing, potentially fruitful global post-New Wave sensibility. (Another potential member of this “cabal” of cinephiles born around 1960 might be Leos Carax, a filmmaker and former critic directly indebted to Garrel.)

What does Garrel have to offer this generation, which was born too late to experience the French New Wave when it was taking shape? For one thing, I would guess, a paring down of filmmaking to certain essentials: the bare facts of private, personal experience and emotion without the encrustations of a self-referential movie culture, a culture launched by Melville, Godard, and others that eventually led to the decadence of Tarantino and company. Because the culture of compulsive hommage, spawned by the New Wave, eventually crowded out — or buried — lived experience in movies that became progressively more related to other movies and less tied to immediate realities, the relative minimalism of a Garrel or an Akerman offered a salutary return to basics, a breath of fresh air.

The Birth of Love sounds about as moldy as a hit-man thriller: an actor named Paul (Lou Castel) going through some sort of midlife crisis periodically bolts from his wife, teenage son, and infant daughter to sleep with younger women (including Johanna Ter Steege). By way of occasional contrast, his friend (Jean-Pierre Leaud), a blocked writer, has just been ditched by his girlfriend (Dominique Reymond) and can’t get over her. The first part of this situation — one can’t call it a plot — unfolds in Paris during the last days of the gulf war in 1991; the remainder happens over no readily discernible time period in Paris, Rome, and an unidentified coastal town and on the road. As with some of the films of Akerman, Eustache, and Pialat, what Garrel offers is basically a restaging of a few slices of his own life — served up fairly raw, with nerves still quivering. Garrel started out as an unabashed experimental filmmaker in the mid-60s, making films in 35-millimeter as well as 16, many of them with New Wave actors (Bernadette Lafont, Zouzou, Jean Seberg, Pierre Clementi), his own actor father (Maurice Garrel), and himself. By the late 70s Garrel had gotten close enough to conventional narrative to make it into art theaters, but prior to that he was sometimes just filming portions of his life rather than restaging them. According to Thomas Lescure, who authored with Garrel the only book about Garrel to date — the 1992 Une camera a la place du coeur (“A Camera in Place of a Heart”) — the filmmaker divides his work into four periods: adolescence (1964-1968, eight films); the Nico years, or underground period (during which Garrel was involved with the singer Nico, who appeared in almost all of his work, 1968-1978, seven films); the “narrative” epoch (1979-1984, four films); and the current period, when he started making more use of dialogue (1988 to the present, at least five films). Having seen at most 8 of Garrel’s 24 films, or about a third of his work, over all four periods, I can only say that the sense of privacy, of living in a small, enclosed world, is fairly constant. This is true even when he’s filming in the deserts of separate continents, as in The Inner Scar (1971); making an uncharacteristic foray into period narrative, as in his powerful evocation of the era of the Algerian war, Liberte, la nuit (1983); and filming conversations in various locations with his filmmaker friends, including Akerman and Carax, in The Ministries of Art (1988).

In The Birth of Love Garrel works gracefully with two New Wave stalwarts, Jean-Pierre Leaud and Lou Castel (both of whom, coincidentally, can be seen next week at the Film Center playing film directors on the same project in Olivier Assayas’s brilliant, exciting dark comedy Irma Vep). Garrel seems to know both of them as well as the back of his hand. And the film has a compositional beauty that can’t be reduced simply to the lighting and framing of shots; it’s also a matter of scenic rhythm and emotional orchestration, and it’s equally apparent in Garrel’s brief, powerful uses of video footage of the gulf war’s aftermath and in the acted sequences. (Viewers who automatically consider the use of this footage and/or of Garrel’s domestic squabbles self-indulgent should be locked up with a video of Al Pacino’s Looking for Richard for the next week.) Garrel’s editing between shots and between sequences allows some of them to run on and nips others in the bud: dropping us into one scene of domestic discord or casual affection or postcoital revelation only to yank us into another is seldom a satisfactory way of spelling out a clear narrative or plotting a dramatic curve. The obstinate sense of privacy and enclosure ensures that we never grasp the full contours of these people’s situations, only intuiting the shape of their lives in snatches. But the cunning way John Cale’s piano improvisations sometimes mesh with the music and emotion of Garrel’s editing, as a patch of discernible melody emerges from the jumble, makes us feel privileged to witness the interaction. A sudden, stabbing flash-cut to an overlit shot of Paul’s latest beloved — apparently a shard of memory, introduced without warning — can be simultaneously written off as an awkward narrative intrusion and cherished as a lyrical burst of pure feeling. This isn’t a movie to be consumed — a fact that will limit its audience, as Garrel’s audiences have always been limited. It’s a movie to be tasted and savored.