From the Chicago Reader (August 2, 1996). — J.R.

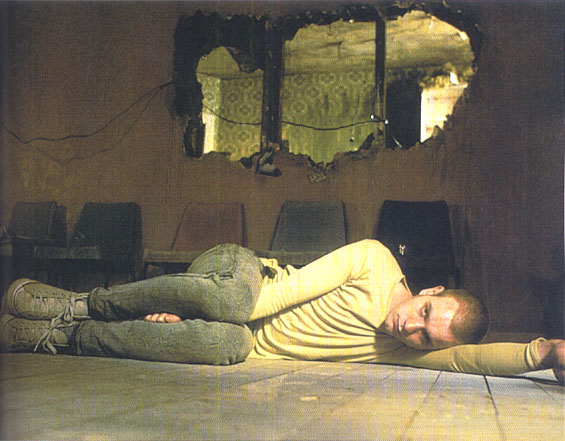

Trainspotting

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Danny Boyle

Written by John Hodge

With Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller, Kevin McKidd, Robert Carlyle, Kelly Macdonald, and Susan Vidler.

It would be pushing it to call Trainspotting a serious work of art or a major statement about anything, but as an edgy, artful piece of entertainment it beats any Hollywood release of the summer by miles. That isn’t much of a compliment. The awfulness of the current crop of “big” (i.e., extensively advertised) summer movies has been so unprecedented that when people ask me how I could find anything halfway nice to say about The Rock and Independence Day, I can only refer them to the even worse dreck they were fortunate enough to miss. Context changes everything: at Cannes, where I first saw Trainspotting, there were at least nine other movies I liked more, and perhaps another seven or eight I liked as much. But in the context of commercial movies this summer, the film unquestionably shines.

Adapted from a 1993 novel by Irvine Welsh, who has a cameo in the movie as a drug dealer, Trainspotting was created by the same team that turned out the much less interesting Shallow Grave: producer Andrew Macdonald, director Danny Boyle, writer John Hodge, lead actor Ewan McGregor, and the same cinematographer, production designer, and editor. It crosses the Atlantic trailing legends: reportedly it’s already made more money in the United Kingdom than any other English movie except Four Weddings and a Funeral, and a dark, less comic play derived from the same novel has had very successful productions in Edinburgh and London. (Ewen Bremner, who plays Spud in the movie, acted in both those productions.)

The press has mainly emphasized the movie’s apparent subject, heroin addiction, and gags involving shit, but what I like most about it is strictly stylistic: the way it handles wall-to-wall music without seeming overloaded a la Spike Lee. The movie chugs along in time to its soft-sell musical accompaniment, from Iggy Pop’s “Lust for Life” to Damon Albarn’s “Closet Romantic.” Never blasted into our skulls in the current Hollywood manner, the sound track implicitly carries the characters from the mid-80s to the present, and nearly all the inventiveness of the mise en scene and editing seems tied to a brisk rhythm in sync with the music. Beginning and ending with the narrator-hero Renton (McGregor) in flight — initially from the law and eventually from his buddies — the film has a sort of mantric literary style in its narration, which begins and ends with delirious rapid-fire lists, both of them describing the kind of life the filmmakers and characters are bent on avoiding.

The first list begins: “Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television. Choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players, and electrical tin openers.” And the final list, really an extension of the first, is set up as follows: “I’m cleaning up and I’m moving on, going straight and choosing life. I’m looking forward to it already. I’m going to be just like you: the job, the family, the fucking big television, the washing machine, the car, the compact disc and electrical tin opener, good health, low cholesterol, dental insurance, mortgage…”

In between are only a few comparable lists — one of them a delightful rundown of what Renton takes out of his shopping bags — but there are strings of episodes and anecdotes, of stories within stories and hallucinated visions within visions, all of which bop along percussively in the same sort of rhythmic patterns. The point of all these accumulations is the verbal, musical, and visual flow they establish; style produces content, including whatever passes for moral content. How we get from one episode to another in this film, from action to reflection, from Edinburgh to London, from addiction to nonaddiction, and from friendship to betrayal isn’t really all that different from how we get from career to family or from washing machine to car.

I suppose one could argue that heroin addiction and the life of crime it engenders produce a comparable compulsive flow — a flow experienced passively rather than actively, where physiological need drives one’s existence. This provides much of the stylistic raison d’etre of William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch as well, which is an even more discontinuous narrative; but in Burroughs’s case it’s a style rooted in his own experience, including several decades of heroin addiction. In the film Trainspotting — I won’t presume to speak of the book, which I haven’t read — the style seems to produce and comment on the experience rather than the other way around. Though the movie can’t be called nihilistic — every style grows out of something, even if it’s only principles of organization and energy, and the movie does have a moral point of view, even if it wears it lightly — it doesn’t make much of a statement about heroin addiction. One of the five buddies, Begbie (Robert Carlyle), doesn’t shoot smack at all, and he’s a much nastier piece of work than the other four. (Women get relatively little attention in such a world; they’re mainly around as setups for gags.)

I guess one could say that Trainspotting is implicitly about the kind of life evoked in the opening and closing monologues and rejected by the characters in between. The film’s attack on this implicit subject — the workaday world that makes shooting up seem an attractive alternative — comprises the movie’s edge, but whether there’s much more to it than that is doubtful. Like Twister and Independence Day, this movie is a theme-park ride — though it’s a much better one, basically a series of youthful thrills, spills, chills, and swerves rather than a story intended to say very much.

Some of the better kicks: Renton’s plunge all the way down “the worst toilet in Scotland” to retrieve a couple of opium suppositories, an interlude possibly inspired by a similar journey in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow; the death of a junkie’s baby, which provides the movie with a passing rush of grim moral reckoning but no further afterthoughts; a variety of hallucinations supposedly provoked by heroin withdrawal; a shot of Renton and his three surviving buddies crossing a London road en route to a drug deal that replicates the album cover of Abbey Road; and — since this is a movie in which even significant speeches, like tragic deaths, are designed for kicks more than for meaning — a monologue about the woes of being Scottish when the lads make an unexpected excursion to the country that registers as a parody of similar scenes in such 60s English flicks as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

A work truly about heroin addiction would surely need to be slow as molasses, like addicts themselves, not breezy like Trainspotting. The best example I can think of, apart from some of the films of the experimental French filmmaker Philippe Garrel, is the Living Theater’s early-60s stage production of Jack Gelber’s The Connection in New York, which I was lucky enough to see three times. There was no curtain on the stage and no clear beginning to the play — just a bunch of junkies sitting around in a dumpy-looking kitchen, waiting for their fix to arrive. The fix didn’t arrive until after the intermission, and during the intermission one of the junkies turned up in the lobby to beg money from audience members to pay for his score. Back in the auditorium, some of the junkies would periodically ask the audience why they were there: had they come to watch a bunch of freaks?

Some of the monologues, which one expected to sum up the meaning of the play, were really just shaggy-dog stories. But thanks to the power of Gelber’s dialogue and the actors — some of whom were jazz musicians who occasionally played hard-bop numbers — The Connection was never boring; or more precisely, whenever it was boring, it was boredom that led you somewhere — into questions about what the actors were doing there and, even more difficult, what the audience was doing there. When Shirley Clarke eventually made a movie of the play (available on video from Mystic Fire) using most of the original cast, the result was often brilliant but lacked the stage production’s confrontational power.

I don’t have much idea what the play Trainspotting is like, but there’s no question that the movie’s agenda is light-years away from that of The Connection; it may brush past some of the same issues, but it doesn’t begin to address them. If the movie is trying to say something about the way certain people live — and I suppose in a half-assed way it is — it doesn’t even have the integrity to preserve its hero’s lack of integrity through the end of the final credits. But it carries one along, thanks to periodic rushes of youth and music and movement, past attractions that might be taken for thoughts if one doesn’t linger on them for too long.