From the Chicago Reader (May 9, 1996). — J.R.

Films by Bela Tarr

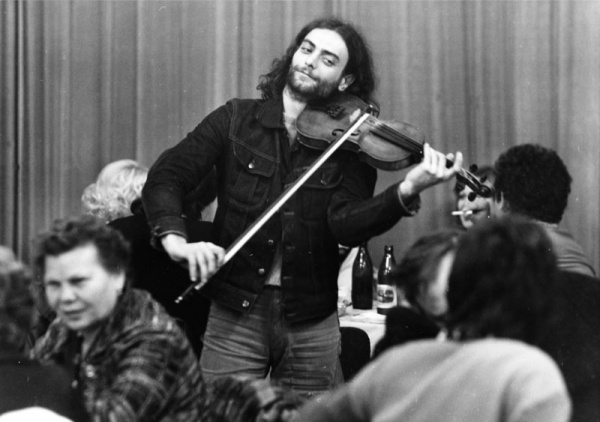

The movies of Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr — half a dozen features in all — are divided into two parts. His first three films are socialist realist cries of rage, much of their style influenced by John Cassavetes. The 1979 Family Nest is about a young couple forced to live in a one-room apartment with the husband’s parents; the 1981 The Outsider focuses on a shiftless, heavy-drinking violinist who fathers a child with one woman and marries another while working sporadically in a hospital and at a factory, then is called up for military service; and the 1982 The Prefab People is about an unhappy family of four: a frustrated wife, two kids, and a disaffected husband and father (another heavy drinker) who plans to take a two-year job in Romania, much to his wife’s distress.

The second half of Tarr’s oeuvre, its style influenced by Andrei Tarkovsky, moves beyond socialism and realism to look with mordant wit at something more universal: a form of moral decay, perhaps, but with metaphysical implications. Whereas the first half of Tarr’s output is mainly shot in raw close-ups, the second half is largely shot in detached medium and long shots. In-your-face actuality gives way to philosophical distance, though the viewer is still strongly implicated in on-screen events.

All six of these features were shown at the Toronto film festival last fall, with Tarr in attendance, but none has received adequate — or in most cases any — distribution in this country. So it’s a tribute to the indefatigable persistence of Facets Multimedia’s Charles Coleman (who’s also recently brought us invaluable retrospectives of Marguerite Duras, Robert Bresson, and Krzysztof Kieslowski) that all six are showing in Chicago this week. Since the death of Kieslowski, Tarr (who turned 40 last year) is conceivably the most important Eastern European filmmaker currently at work, but he doesn’t have the instincts for packaging that made Kieslowski into something resembling a household name. Tarr’s 1994 magnum opus Satantango — which took him years to develop (accounting for the seven-year gap after Damnation) — runs a little under seven hours and is meant to be seen with two short intermissions. It attracted a sizable audience at the Chicago International Film Festival two years ago, most of which stayed not only to the end but through an additional hour of discussion with Tarr afterward. The two screenings it will have this weekend will be the only local showings since then.

Almanac of Fall (1984) and Damnation (1987), my two other Tarr favorites, had runs at Facets several years ago, and the former is now available on video on the Facets label. But the rare opportunity to see all six of Tarr’s features on film over a single week allows one to observe continuities as well as changes, throwing a different light on his work as a whole. Though the first three are less appealing to me as well as less familiar, they’re still full of interest in their own right. And they offer fascinating glimpses of where the three later movies come from.

If you’re wondering why you haven’t heard much about Tarr, it may be because the nature and seriousness of his work would get in the way of the marketplace flow the mainstream media are geared to promote. Case in point: Tarr is mentioned twice in Susan Sontag’s provocative, passionate essay about the decline and dissolution of cinephilia printed earlier this year in various publications around the globe, both times in contexts that make it clear she regards him as one of the few important filmmakers in the world. But when the New York Times Magazine printed the essay in its February 25 issue, both references were omitted, along with allusions to other directors (Theo Angelopoulos, Miklos Jancso, Alexander Kluge, Nanni Moretti, Krzysztof Zanussi) who have not curried much favor in recent years with New York Times reviewers or U.S. distributors. (It’s usually impossible to win favor with the latter if the former aren’t won over.) Conversely, the Times version of Sontag’s essay includes references to Francis Ford Coppola and Paul Schrader that weren’t in the original version (they’re cited as “artistically ambitious American directors” who haven’t been able “to work at their best level” because of “the lowering of expectations for quality and the inflation of expectations for profit” in this country). In other words, even in an article decrying Hollywood’s ruinous effects on world cinema, Hollywood directors had to be given more attention — and European directors less — when the piece was published in the United States.

What’s going on? It seems that Americans’ relative ignorance about film elsewhere in the world is being protected, even honored, just as it is in the widely applauded latest edition of David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema. In much the same way, some parents avoid discussing certain topics in front of the children. I would even argue that Sontag’s original essay underwent a more sophisticated version of the same screening process, because she neglects certain recent filmmakers in the East, Iran, and Africa. Of course it’s also possible that Sontag is familiar with Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, Stanley Kwan, Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Ousmane Sembène, and Souleymane Cissé and thinks less highly of them than I do.

Sontag first refers to Tarr as part of a discussion of directors who are cinephiles: “Cinephilia — the source of exaltation in the films of Godard and Truffaut and the early Bertolucci and Syberberg; a morose lament in some recent films of Nanni Moretti — mostly a Western European affair. The great directors of ‘the other Europe’ (Zanussi in Poland, Angelopoulos in Greece, Tarkovsky and Sokurov in Russia, Jancso and Tarr in Hungary) and the great Japanese directors (Ozu, Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, Oshima, Imamura) have tended not be cinephiles, perhaps because in Budapest or Moscow or Tokyo or Warsaw or Athens there wasn’t a chance to get a cinema-theque education.” This is certainly true in Tarr’s case, though what I find off-putting about his first three features is not merely the absence of cinephilia but what amounts to impatience with cinema itself; he seems to focus almost exclusively on content and shows scant interest in style. This tendency is radically overturned in the second three features, which have a taste and an intelligence that are specifically (and exquisitely) cinematic, revealing Tarr to be a master stylist.

Sontag’s second reference to Tarr, after she cites Damnation and Satantango as his two exemplary works, is a voicing of concern about his future as a filmmaker, since “the internationalizing of financing and therefore of casts” has had disastrous effects on the careers of Tarkovsky, Zanussi, and Angelopoulos. On this front, I can report that Tarr is preparing to shoot his seventh feature this fall, and to the best of my knowledge has not had to compromise his intentions by being forced to use an international cast or in any other respect.

As critic Bérénice Reynaud cogently suggested in Cahiers du Cinéma last November, the way that Tarr’s characters’ thoughts and emotions are connected to the spaces they inhabit is inextricably tied to the philosophical and moral investigations of his films. Thus the acute housing shortage in Budapest during the late 70s and 80s has an immediate bearing on Family Nest and Almanac of Fall, Tarr’s two most claustrophobic films (though The Outsider and The Prefab People aren’t far behind). And the endless stretches of rural wasteland in Damnation and Satantango are the visual counterparts of people’s mutual distrust and alienation from one another.

Even more fascinating is the missing link between the two halves of Tarr’s work: how did he get from socialist realism to the dark metaphysical mode of his more recent films? A 72-minute video production of Macbeth that Tarr staged for Hungarian television in 1982, shortly after completing The Prefab People, and which will be shown at Facets twice on Friday, provides a clue.

The entire video consists of only two shots — the first (before the main title) about 5 minutes long, the second 67 minutes long. Practically all the important action is staged in the foreground, with the camera following some characters and picking up others as it relentlessly tracks their movements and machinations through fog, torchlight, and dank, grottolike settings. Though I could follow the action only in the most general way, it’s striking how much this video reprises elements from Tarr’s first three features while anticipating the extended, choreographed camera movements and metaphysical demonology of his second three. Even Andras (Andras Szabo) — the hero of The Outsider — turns up with his violin to furnish part of the musical accompaniment on-screen.

It’s almost as if Tarr, determined to discover the roots of contemporary rottenness, were driven to formulate a satanic theology to account for it — a theology, I hasten to add, that he appropriates poetically rather than religiously. The very titles Damnation and Satantango reveal this theology, as does the quotation from Pushkin that begins Almanac of Fall (in a highly unidiomatic translation): “Even if you kill me I see no trace / This land is unknown / The devil is probably leading / Going round and round in circles.” More generally, Tarr’s demonology can be felt in all three films in the grubby human behavior he puts on display — behavior imparting a feeling that the universe itself is out of joint, and accompanied in Damnation and Satantango by a black-and-white wasteland stretching in all directions.

Tarr himself wrote his first four features, but he wrote Damnation and Satantango in collaboration with the Hungarian novelist Laszlo Krasznahorkai, who wrote the novel, Satantango, on which the film is based. (The two also worked together on a short film I haven’t seen –t he 1989 “The Last Boat,” included in the international sketch film City Life.) Their collaboration began when Tarr read Krasznahorkai’s novel as an unpublished manuscript in the mid-80s, so in effect their latest film was formulated over a full decade. Regrettably, this novel isn’t available in English (though I’m told an excerpt was translated in the winter 1986 issue of New Hungarian Quarterly, which I’m still hoping to track down).

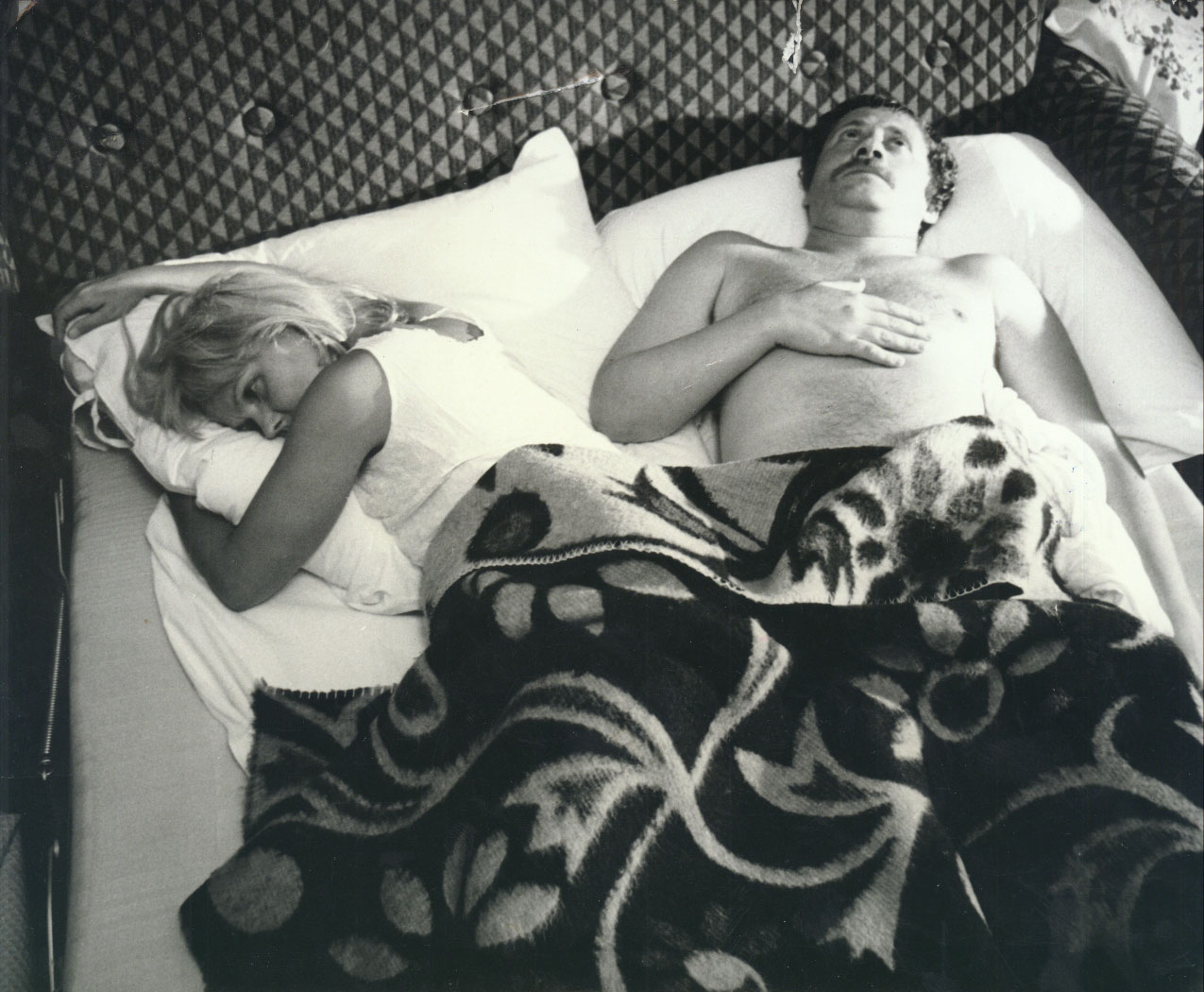

Like Macbeth, all three of Tarr’s most recent films feature a good deal of underhanded conniving. Almanac of Fall, set exclusively in an old woman’s apartment, records the struggles over money and supremacy between her, her son, her nurse, the nurse’s lover, and a lodger. Meanwhile the camera is constantly on the prowl, capturing the characters from every possible angle (even from above their heads and, at one startling juncture, under their feet), recording and wryly commenting on their Strindbergian power plays; bold colors and lighting are also part of Tarr’s expressive arsenal. (He employs color at length in only two of his features, generally preferring the rigor of black and white.) Damnation is the most formalistic of his films: the characters and plot (a classic Eastern European adultery intrigue set at a grimy mining outpost) are relatively sketchy, but the mise en scène is so richly orchestrated that it almost seems to function independently of the narrative, conjuring up an indelible sense of place and an apocalyptic mood of blighted, festering impulses deriving from solitude.

The story line in Satantango — brilliant, diabolical, sarcastic — gradually unravels the dreams, machinations, and betrayals of a failed farm collective over a few rainy fall days, two of them rendered more than once, from the perspectives of different characters. But the plot operates almost independently of the moral and experiential weight given each shot: Tarr’s camera obliges us to share so much time as well as space with the grubby characters that we can’t help but become deeply implicated in their lives and maneuverings. Tarr has noted that the form of his film, like that of the novel, is inspired by the tango — six steps forward, six back –an idea reflected in the overlapping Faulknerian time structure, the film’s 12 sections, and many of its remarkably choreographed camera movements and long takes.

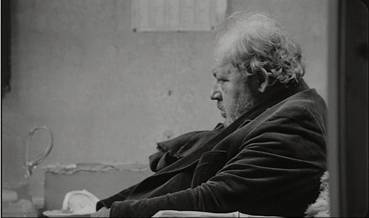

Satantango weaves the collective interactions of Almanac of Fall and the pungent evocations of solitude of Damnation into the same narrative fabric; though the film focuses on a community, at least three of the most remarkable sequences follow the movements of an isolated individual. The most celebrated and terrifying of these, involving a little girl and a cat, is rendered so convincingly that many viewers have wrongly assumed its violence to be real rather than fabricated. (For the record, the cat used in the sequence is now a pet of one of Tarr’s friends.) Even more extraordinary, to my taste, is the film’s mesmerizing third section, which charts for a full hour the mainly solitary movements of an old doctor lost in an alcoholic haze. It’s a tribute to Tarr’s singularity of purpose that at no point does this sequence — or anything else in his 415-minute film — seem tedious or self-indulgent; the breadth of his canvas suits the magnitude of what he has to say.