From the November 10, 1995 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

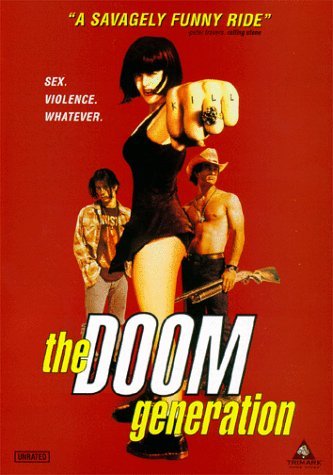

The Doom Generation

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Gregg Araki

With James Duval, Rose McGowan, Johnathon Schaech, Cress Williams, and Dustin Nguyen.

Kicking and Screaming

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Noah Baumbach

Written by Baumbach and Oliver Berkman

With Josh Hamilton, Olivia d’Abo, Chris Eigeman, Jason Wiles, Carlos Jacott, Eric Stoltz, Elliott Gould, Cara Buono, and Parker Posey.

Chet: Here’s a joke. How do you make God laugh?

Grover: How?

Chet: Make a plan.

— Kicking and Screaming

As luck would have it, I had my second looks at The Doom Generation and Kicking and Screaming, two radically different youth movies about defeat and paralysis, back-to-back. Both seemed better the second time around, though for very different reasons. Noah Baumbach’s first feature, Kicking and Screaming, which I’d originally seen and liked at Cannes last May, seems to have been tightened up in the editing and given more focus. Perhaps because I disliked Gregg Araki’s fifth feature, The Doom Generation, when I first saw it last August, I found it harder to decide on a second viewing whether it had been changed in the interim; in any case I found myself disliking it less.

Expectations had something to do with my first impressions of both movies. Baumbach is the son of a friend of mine, Village Voice film critic Georgia Brown, which means that I have a nodding acquaintance with him and wanted to like his movie. I’ve never met Araki, although we’re both survivors of the film program at the University of California, Santa Barbara — he as a student, I as a teacher — and he once wrote me a friendly letter after I favorably reviewed his second feature, The Long Weekend (o’ Despair). I was disappointed, however, by the two subsequent Araki features I saw, Totally F***ed Up and The Living End, both of which seemed much more strident. I wasn’t looking forward to more of his in-your-face aggressiveness, which The Doom Generation delivers in spades. “A heterosexual movie,” announces the opening title ironically, but we discover before long that just about the only heterosexual activity in the movie is the kind that sublimates or redirects the men’s latent homosexuality.

The three characters at the center of Araki’s new movie are two young lovers, Jordan White (James Duval) and Amy Blue (Rose McGowan), and a lawless drifter they pick up named Xavier Red (Johnathon Schaech). The color-coded surnames make it clear from the outset that stylization is very much the name of Araki’s game, so don’t expect full-blown characters with coherent pasts or imaginable futures. Even if this weren’t clear, the very first scene establishes a world of comic-book exaggeration and formal abstraction; it’s set in a raucous club ablaze with syncopated strobe lights and the announcement “Welcome to Hell.” The film never strays very far after that from loud colors and minimalist decor.

For that matter, the first of many scenes of violence is so gratuitous and outlandish that we’re obviously meant to salivate in Pavlovian fashion, however satiric or “distanced” Araki’s intentions might be. When Amy lights a cigarette inside a Quicky-Mart decorated with huge signs announcing “Shoplifters Will Be Executed” and “America…Love It or Leave It,” the Asian-American clerk orders her to put it out; after she grinds it under her heel, he orders her at gunpoint to dispose of the butt. She complies, and she and Jordan announce that they don’t have the $6.60 they need for what they’re buying and have to go back to their car for the cash. The clerk makes threatening gestures, and Xavier — whom they’ve already encountered at the club — promptly blows the clerk’s head off with a gun; the head sails across the store, following a gushing spray of blood, and the mouth of the severed head continues to move and make gargling noises after it falls with a thud like a pumpkin. A little later, on a motel room TV, we discover from two parodic (and rather funny) anchorpeople that the clerk’s name is Win Cock Suck and that his crazed wife responded to the murder by slaughtering their children.

By this time, however, such harsh, over-the-top details register as routine, because the whole movie is pitched at this level. The talk among the trio on the run consists almost exclusively of lines like “You can relax your royal sphincter muscles, your highness” and epithets like “jism breath,” “ass crack,” and “scum fuck”; I suppose we could read such language as a cover-up for fear and vulnerability, but it also seems calculated to elicit callow audience approval. Many other details too seem not so much indirect revelations of character as pure exploitation jive. We see Xavier jerk off while Amy and Jordan have sex in the bathtub, then lick the semen off his hand; and when Xavier gets around to having sex with Amy as well, we learn right away that an image of Jesus Christ is tattooed on his prick (at which point I guess we’re meant to exclaim “Far fucking out” or its equivalent). Later the guys discuss formerly “having sex” with a golden retriever and a cantaloupe. So by the time they get around to rape, castration, murder, and homophobic /fascist rant performed on top of an American flag to the national anthem and accompanied by the same strobe effects as at the club, we’re likely to feel pretty ho-hum about it all; I know I did.

If this is independent cinema’s alternative to Natural Born Killers, I can’t see that it represents much of an improvement. It adopts the same specious pretext that we’re gazing deep into the dark American unconscious rather than catering to the audience’s worst instincts; and it advances the same duplicitous claim that parody of excess is somehow different from plain old excess — a claim that becomes just another pretext for heaping on more. The embrace of negativity and cynicism — as much a staple of contemporary commercial filmmaking as the standard happy Hollywood ending was of yore, and every bit as much an evasion of reality — is proffered dishonestly, as if it were simply arrived at by looking at the world rather than at the box-office grosses in Variety.

So much for what I still dislike about The Doom Generation. But it must be said that Araki occasionally pauses long enough to treat his threesome with a certain tenderness and pity, the same sort of feelings that gave The Long Weekend (o’ Despair) much of its distinction. (I only wish Amy received as much understanding as Jordan and Xavier do — though Araki does devote an interesting if highly ironic scene to her grief when they accidentally run over a dog, which elicits more compassion from her than any human being has. In another good scene she confesses her infidelity to Jordan, who professes not to mind at all.) Equally commendable is Araki’s consistent effort to fully create the movie’s space rather than merely fill it, as most movies do. One comes away from this movie, as one does from some of the films of Araki’s two obvious models, Jean-Luc Godard and Jon Jost, with sounds, images, and feelings more than characters and plot, and ultimately the overall expressionist effect may count for more than the lurid parade of individual shocks and sensations.

Before looking at Baumbach’s auteurist credentials, it’s worth giving some attention to the commercial context for Kicking and Screaming. The producer is Joel Castleberg, who served as executive producer on Bodies, Rest and Motion and Sleep With Me, both “Generation X” movies starring Eric Stoltz that bear more than a passing resemblance to this comedy. Indeed, I’m told that Kicking and Screaming was made on the condition that a part be added for Stoltz. (He plays a long-term philosophy major and bartender, a role apparently written shortly before the movie went into production.)

Structured around a single college semester — a format signaled by such titles as “Midterm” and “Only One Month Until Christmas Vacation!” — Kicking and Screaming begins with a college graduation party that introduces the four graduating heroes, all of whom are at a loss about what to do next: Grover (Josh Hamilton), Max (Chris Eigeman), Otis (Carlos Jacott), and Skippy (Jason Wiles). It’s hard to keep their names and faces straight, especially when all four remain on campus for the next half year; I can’t say I always had a clear sense of who was who. Surely this is part of the point, but that fact doesn’t help the struggling viewer. On two separate occasions a female character remarks, “You guys all talk alike” — but whether this was two female characters or the same one also eludes me now. At least it isn’t just the male dialogue that’s undifferentiated. But generally, as other reviewers have noted, the women characters tend to understand their own lives and futures better than the men do theirs, though virtually everyone is occasionally limited in his or her ability to function by endearing eccentricities.

The main mover in this world seems to be Jane (Olivia d’Abo), Grover’s former girlfriend (her eccentricity is a habit of removing her retainer while she’s talking). A onetime coffeehouse waitress, Jane decides to study in Prague rather than live with Grover in Brooklyn, thereby sending him into a funk that lasts most of the remainder of the movie, keeping him on campus along with his no more decisive friends. (Otis can’t even board a plane to attend graduate school, one time zone away.) When Grover’s father (Elliott Gould), who recently separated from his mother, turns up to visit him — my favorite scene, perhaps because it has so much to say about the uneasy interactions between fathers and sons — Grover can’t even commit to staying in his dad’s Greenwich Village apartment while he’s away. Meanwhile Jane calls periodically from Prague, leaving Grover various messages, but he never calls her back.

Baumbach has worked as an intern at the New Yorker — a job coyly alluded to as a possibility for Grover in one scene — and has written a New Yorker piece or two, so it’s no surprise that most of his bantering dialogue suggests that magazine’s worldview. If a prototypical line of dialogue in The Doom Generation is “Will you kindly pull your head out of your rectal region?” in Kicking and Screaming it’s “Somebody got up on the wrong side of the futon this morning.” (This isn’t to say that Baumbach doesn’t have a penchant of his own for baroque obscenity. His cameo in the film is devoted to asking another guy, “What would you rather do, fuck a cow or lose your mother?” When the guy says, “Fuck a cow,” Baumbach promptly calls him “cow-fucker.”)

At its worst, Baumbach’s dialogue suggests some of the smart-ass dandyism of writer-director Whit Stillman (an impression fostered by the presence of Chris Eigeman, who starred in both of Stillman’s features, Metropolitan and Barcelona). Baumbach salts his supposed urbanity with liberal rather than conservative trimmings, however. What ultimately saves the dialogue, in my view, are the lovely performances Baumbach coaxes out of his actors, all of whom tend to treat the witticisms as material to play against rather than simply deliver. Baumbach said that Jean Renoir is his favorite director, and there’s a genuine quirky curiosity about people in this movie that validates this taste — a desire to move beyond the characters’ cover stories. This sense of discovery is something Araki seems to find only in his arsenal of formal devices.

The main thing that Araki and Baumbach have in common is their dialogue — not its style, which is radically different in each case, but its function as emotional camouflage, a kind of compulsive delaying action designed to disguise not knowing what to say or do. But perhaps because Baumbach’s characters are more educated, they’re a good deal more self-conscious and self-critical than Araki’s. In one of many flashbacks to Grover’s first encounters with Jane, she notes in passing that she hates raisins, adds that her mother used to make her eat them, then gives Grover 50 cents as a self-imposed penalty for telling him a “bad story.” (Grover, declaring that he likes the story, insists on pocketing only a quarter.) Significantly, they first meet at a writing seminar presided over by Baumbach’s father, novelist Jonathan Baumbach, where Jane tears into Grover’s short story for its triviality.

The male leads in both movies recall the title of Saul Bellow’s first novel, Dangling Man; if Araki’s two heroes dangle over their unresolved sexuality, Baumbach’s dangle over their vocations and purpose in life. And contrary to what Chet tells Grover at the head of this review, God probably laughs more at the absence of plans, an absence all these dysfunctional guys are confronting. For as both movies show, not having plans generally turns out to be as exhausting, as time-consuming, and as draining a project as having them.