From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 1992). For earlier reflections on both films, go here and here. — J.R.

TWHYLIGHT (DUELLE)

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Eduardo de Gregorio, Marilu Parolini, and Rivette

With Juliet Berto, Bulle Ogier, Hermine Karagheuz, Jean Babilee, Nicole Garcia, and Jean Wiener.

NOR’WESTER (NORÔIT)

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Eduardo de Gregorio, Marilu Parolini, and Rivette

With Geraldine Chaplin, Bernadette Lafont, Kika Markham, Larrio Ekson, Jean Cohen-Solal, Robert Cohen-Solal, and Daniel Ponsard.

Dagger in hand, I scaled the heights of raw power, thanks to the male role that Rivette gave me. . . . This kind of sexual metamorphosis, this strange androgyny, never appeared in the French cinema before Rivette. After I performed the role of Giulia in Norôit I felt that I was capable of anything. Rivette changed my ideas about acting; for me, he is a kind of Mao and his films are a Cultural Revolution. — Bernadette Lafont in an interview, 1977

Though no one would ever think to call Jacques Rivette a realist, the fact remains that all of his first six features take place in a sharply perceived environment that can arguably be called the “real world.” An acute sense of place and period brought into focus largely by means of “documentary” techniques informs these haunting movies, giving them all a pungent flavor that can only be described as the taste of a particular time, milieu, and culture. But because they’re quintessentially French — Gilles Deleuze has aptly written that Rivette is the most French of the New Wave directors who came to prominence in the 60s — fantasy might be said to form an essential part of the texture of this real world.

In Paris Belongs to Us (1960), L’amour fou (1968), and the separate 4- and 12-hour versions of Out 1 (1971 and 1972), the fantasies tend to be paranoid, having to do with conspiracy and betrayals, concealed plots and machinations. In The Nun (1966), an adaptation of a Diderot novel set in the 18th century, these fantasies all evoke freedom, chiefly through the film’s sound track — the “outside” as experienced by a nun confined to her cell. And in Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), in which the heroines’ word-spinning fantasies eventually give birth to an alternative plot that the two periodically enter, the world they inhabit at the outset is firmly anchored in a vivid sense of Montmartre during a lazy summer. In effect this initial setting corresponds to the first two paragraphs of Alice in Wonderland — that drowsy, necessary moment on a riverbank before Alice notices that the rabbit rushing past her is actually speaking.

Twhylight and Nor’wester, the two features Rivette made in 1976, break profoundly with this tradition, and the six features he’s made since, including the recent La belle noiseuse, have been different as a consequence. (These are the designated English titles of the 1976 features, though they’re better known as Duelle and Norôit respectively. Significantly, both the English and French titles of both films are invented words: “duelle,” for instance, is the feminized form of “duel,” which has the same meaning in French as in English.) Though Rivette’s last eight films, including Twhylight and Nor’wester, make use of the “documentary” techniques (such as direct sound recording) that characterize his first period, one’s sense of a real and recognizable world in them is much more attenuated. Some might even argue that Rivette’s work has never fully recovered from the profound rupture created by these two films. Both represent violent rejections of the contemporary world, including a retreat from politics — a position that has to be seen in relation to the failed French revolution of May 1968, the implicit subject of Out 1 — though both can be read as psychodramas full of political implications. It may be significant that Cahiers du cinéma, the magazine that has been most supportive of Rivette’s work and that was for 16 years the principal outlet for his own criticism, has never dared to run a review of either movie. (They were originally meant to be parts two and three of a quartet of features to be called Scenes de la vie parallel — “Scenes of Parallel Life.” It was never completed.)

Rivette once remarked that Griffith’s Intolerance has more to say about the year in which it was made, 1916, than about any of the historical periods it covers. In the same way, 60 years later, Twhylight and Nor’wester undoubtedly have a lot to say about 1976, but these films confound any ordinary definitions of period by deliberately making all their temporal references inconsistent: in fact they could be called transitional works between the modernism of Rivette’s first six features and the postmodernism of his last six.

His original intention was to shoot all four films of the quartet in swift succession, then edit them in the order of their releases. But after suffering a nervous collapse a few days into the shooting of the third feature — intended to be part one of the series, starring Albert Finney and Leslie Caron — Rivette decided to edit each of the two films he had already shot and canceled the other two. Duelle, the first edited, had a very brief run in Paris; Norôit has never opened in France at all. Tonight these rarely seen movies are starting their first run in Chicago at Facets Multimedia, where they will play for a week.

All four films were to take place within a partially invented mythological framework corresponding to the 40 days of the traditional carnival cycle, a period that includes three lunar phases when rival goddesses of the moon and sun come to earth and mingle with mortals. All the films were to feature on-location and on-screen musicians improvising live accompaniment to the action without functioning as characters themselves, and each film would employ a different kind of music. The first film would be a love story, the second a film noir thriller, the third a pirate adventure, and the fourth a musical featuring Carolyn Carlson’s modern dance company; Rivette intended to increase the amount of music from one feature to the next.

The proposal Rivette drafted to acquire a state subsidy for this mad, ambitious project included the following passages:

“The ambition of these films is to discover a new approach to acting in the cinema, where speech, reduced to essential phrases, to precise formulas, would play a role of “poetic’ punctuation. Not a return to silent cinema, neither pantomime nor choreography: something else, where the movement of bodies, their counterpoint, their inscription within the screen space, would be the basis of the mise en scène. . . .

“To create one’s own space through the movements of one’s body, to occupy and traverse the spaces imposed by the décors and the camera’s field, to move and act within (and in relation to) the simultaneous musical space: these are the three parameters on which our actors are going to attempt to base their work.”

In contrast to the films that immediately preceded and followed this project — Out 1 and Celine and Julie Go Boating before, Merry-Go-Round and La pont du nord after — the actors did not improvise any of their lines or collaborate on the scripts; their creative contributions were strictly a matter of their facial expressions, poses, and gestures. By design, however, the scripts were merely sketched out in skeletal form before the films went into production, and the dialogue was usually written each day only a few hours before shooting. The general idea was to arrive at the unexpected through the chance encounters between particular actors, locations, and dramatic situations, inflected in diverse and unforeseeable ways by the music.

I had the opportunity to watch part of the shooting of both films — three full days on Twhylight, five on Nor’wester –– and they were drastically different from any other shootings I’ve ever witnessed, and considerably more exciting. Most shootings are dull because of the technical delays and programmatic approaches toward creativity, usually intended to realize an idea thought up long before. Rivette’s suspenseful shootings were full of surprises as the moods of various scenes shifted and developed. Much of this was the result of the musicians’ improvisation during and between takes, and much of it came from Rivette’s own desire to be surprised by what he saw.

I was also present at the world premiere of Nor’wester at the London film festival. Rivette introduced it by cheerfully announcing that the main reason he’d wanted to become a film director was to meet his favorite actresses. I pass on this disconcerting comment because it points to an aspect of both films that has made them difficult to deal with critically. While neither contains any significant nudity (in contrast to La belle noiseuse), both have an essentially worshipful relation to their actresses that has very different ideological implications in each film — and ambiguous implications in both. While experimental filmmaker Yvonne Rainer and critic Annette Michelson both indignantly walked out after only ten minutes of one of the first screenings of Twhylight because of what they perceived as its sexism, Bernadette Lafont, who played the dictatorial head of a band of pirates in Nor’wester, subsequently praised Rivette as a sexual revolutionary (in the interview quoted above). Curiously, all three women may have been right.

The mythological framework of both films reflects Rivette’s compulsive cinephilia — in particular, a simultaneously serious and ironic view of movie actresses as goddesses. It’s worth adding that goddesses and mortal females are the prime movers in both movies, although only in Nor’wester do they assume the positions of power usually accorded to men. (In both films the male characters are secondary. The two who are most prominent — Pierrot [Jean Babilée] in Twhylight, Ludovico [Larrio Ekson] [right, below] in Nor’wester — are played by very graceful dancers, and the others, all in Nor’wester, are treated chiefly as love objects by the female pirates.) There’s also a significant class difference between the goddesses and the mortals, although this is much more apparent in Twhylight than in Nor’wester.

In both films the identities of the sun and moon goddesses are clarified belatedly — the revelations come especially late in Nor’wester — and both plots eventually hinge on the possession of a precious magical jewel that will allow the goddesses to remain on earth past their allotted 40 days and thereby become mortal. It also destroys mortals, bringing on madness and death, in the process of converting them into immortal deities. In both films the intense desire to possess this jewel might be likened to the kind of desire set in motion by film narrative itself: “mortal” viewers wish to become “immortal” through their emotional investments in movie stars, and “immortal” movie stars wish to become “mortal” — ordinary folks like you and me — through their emotional identification with viewers.

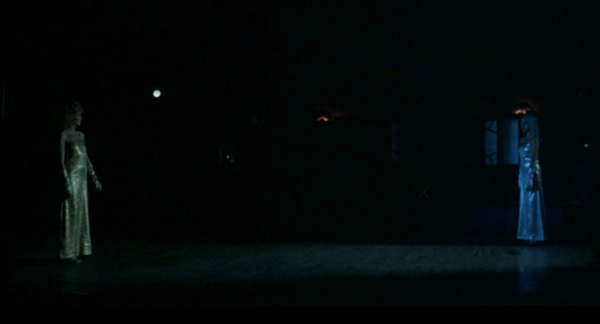

The mythological framework of the sun and moon also influences the visual design of both films, affecting costumes, makeup, and the lighting of certain scenes. The various phases of the moon are motifs in both, and in the climactic sequence of Nor’wester the unmasking of the characters is echoed by the “unmasking” of the full moon as clouds drift past it.

Rivette drew on specific sources for the style and much of the dialogue in these films. Before each was shot, he screened a different Hollywood movie for the cast and crew. Mark Robson’s The Seventh Victim (1943), probably the best of all the masterful black-and-white horror quickies produced by Val Lewton, was the stylistic reference point for Twhylight, and Fritz Lang’s lyrical and evocative color period adventure Moonfleet (1955) served the same function for Nor’wester.

Both films also incorporate many lines of dialogue from particular plays — Jean Cocteau’s Chevaliers de la table ronde (1937) in Twhylight, and Cyril Tourneur’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (1607 or 1608) in Nor’wester. These lines are often wrenched out of context, though. In Nor’wester, the Tourneur lines are all recited in English by Geraldine Chaplin and Kika Markham, the two English-speaking actresses in the cast. The role played by the Jacobean tragedy is more substantial in Nor’wester than that of the Cocteau play in the earlier film: printed titles indicating the act and scene numbers of the Tourneur play appear throughout, and I’m told that the film’s main inspiration was screenwriter Eduardo de Gregorio’s description to Rivette of an Italian production of the play in which the sexes were reversed. The weird English spellings that crop up in the subtitles during Nor’wester‘s final sequence — a “masquerade ball” that concludes with all the remaining characters killing each other off — are deliberate efforts to evoke Tourneur’s archaic English, and were done in consultation with Rivette himself.

In Twhylight, the film noir references go far beyond allusions to The Seventh Victim. Many of the settings are prompted by other noir classics — an aquarium from The Lady From Shanghai, a greenhouse from The Big Sleep, a row of lockers from Kiss Me, Deadly (whose “Great Whatsit” — a Pandora’s box containing nuclear energy — bears more than a passing resemblance to this film’s deadly but sought-after jewel). The Cocteau references also go much further than the quotations from Chevaliers de la table ronde: I’m thinking especially of the uses of mirrors, the casting of Jean Babilée (who performed Cocteau’s ballet Le jeune homme et la mort in the 40s), and a setting and crucial line (“Je me revengerai”) that both derive from Robert Bresson’s rather noir-ish Les dames du bois de Boulogne, which Cocteau wrote the dialogue for.

When Twhylight and Nor’wester were screened one after the other at the London festival in 1976, Rivette mentioned to me afterward that it probably wasn’t a good idea to see them both together. I’ve just seen them back to back a second time — as well as separately many other times — and I tend to agree. Each movie is a full meal in itself, and despite their interesting similarities, they are still too different to establish a context together that’s mutually enhancing. It’s probably better, however — though not strictly necessary — to see them in the order in which they were made.

If I had to recommend one film over the other, it would be hard to know which one to choose. Twhylight has a much more difficult plot but is perhaps the more conventionally beautiful: its reinvented, somewhat campy Paris of plush casinos and archaic dance halls alludes to many periods at once but can still be loosely located within a tradition of nostalgic French fantasy shared by such filmmakers as Cocteau and Georges Franju. Its live music is performed almost exclusively by pianist Jean Wiener, a veteran composer who scored many films for Jean Renoir, and consists mainly of antiquated-sounding ditties and tangos. (As in Nor’wester, the live music crops up in plausible or semiplausible settings — a hotel lobby, casino, dance hall, and dance studio–as well as completely implausible ones, such as a hotel room and aquarium. The means by which the camera discovers or doesn’t discover Wiener in these settings, and the ways in which the actors respond to or ignore his music, are both fascinating and unsettling.)

Nor’wester is easier to follow, more spectacular in terms of its locations (a 12th-century fortress on the Brittany coast and a reconstructed 17th-century chateau), and considerably more outlandish — and therefore more difficult — in its emotional tone and affect. Properly speaking, it belongs to no recognizable era or film genre; the female pirates could be 17th-, 18th-, or 19th-century characters, although they use a telegraph and radio in an early scene and at least one ship is motorized. At different junctures Nor’wester suggests a western, a pirate film, a violent Jacobean tragedy, a 19th-century romantic melodrama complete with incest, a demonic (or klutzy) black comedy, a radical lesbian SF war film, a musical, and an experimental dance pageant. The music — played by a gifted trio, Jean Cohen-Solal, Robert Cohen-Solal, and Daniel Ponsard, who also contributed a few eerie sound elements to Twhylight — runs the gamut from modernist free jazz to neoprimitive folk, employing everything from flutes and traditional European stringed instruments to African and South American percussion.

Both movies suddenly cut to black and white in climactic sequences. Both explore uncanny acting registers that veer unexpectedly from frivolous to fiendish, from passionate to parodic; and both occasionally abandon dialogue altogether and express the drama in terms of pantomime or dance. (Interestingly enough, some of Chaplin’s aggressive gestures and abrupt, angular movements can also be found in her subsequent performance in Alan Rudolph’s Remember My Name.) Both are structured around the successive elimination of all the characters, and both are remarkable and eclectic constructions of mise en scène, with elaborately plotted camera movements and many unconventional cuts. And both, in the final analysis, do so many things to unhinge our notions of what movies are that we may remember them afterward like shards of unfathomable dreams — beautifully textured and intensely realized reveries that obstinately evade all our usual methods of understanding and appropriation.