From the Chicago Reader (July 5, 1991). –J.R.

TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by James Cameron

Written by Cameron and William Wisher

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton, Robert Patrick, Edward Furlong, Earl Boen, and Joe Morton.

As much a remake as a sequel, James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day begins, like The Terminator (1984), with a postnuclear Los Angeles in the year 2029, a world ruled by deadly machines where a few scattered remnants of humanity struggle to survive. Then the film leaps backward in time — not to 1984, when most of The Terminator took place, but to 1997, when the Terminator materializes in virtually the same mythic fashion, crouched naked like a Greek god, before rising and setting about finding the proper attire. This time he enters a bikers’ bar, where he quickly appropriates the clothes, boots, and bike of one tough customer and the shades of another, blithely smashing the skulls of whoever happens to get in his way.

The thrill and beauty of the Terminator, both as a character and as a concept — the ultimate Schwarzenegger role, against which all his other roles must be measured — resides in the excitement of witnessing a brutal, dispassionate machine, a weapon slicing impartially through metal, flesh, or bone en route to its unambiguous goal. In The Terminator this goal was to locate and kill a young woman named Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton). Sent back in time by the machines that rule 30 years later, the Terminator can change the course of history if he kills Sarah: she’ll never give birth to the man who will otherwise one day lead a rebellion against the machines. Unfortunately for the machines, a human time traveler from 2029, a young guerrilla fighter named Kyle Reese, turned up to save Sarah, also managing to father her savior-to-be son before perishing in an explosion that obliterated most of the Terminator as well.

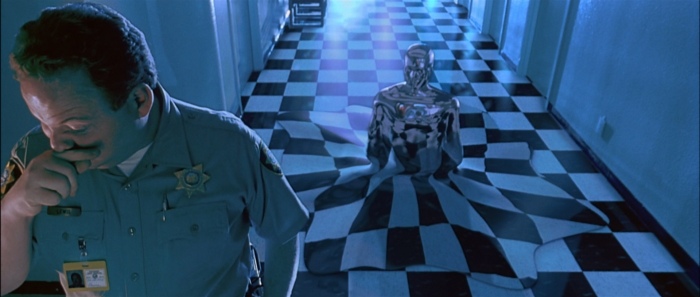

This time it’s a little different. A resurrected version of the Terminator, now working for the human resistance forces of 2029, returns to the past to protect Sarah’s 12-year-old son John (Edward Furlong), now living with foster parents while Sarah is in a mental ward, diagnosed as schizophrenic because of her statements about the future. The Terminator’s new opponent is not a human but another, even more high-tech, killing machine (Robert Patrick). Sent back in time to destroy John Connor it appropriates the clothes of a cop and turns out to have the talent of replicating any human it comes in contact with. This capacity refers back intertextually not to The Terminator but to Cameron’s The Abyss (1989), where a benign extraterrestrial force, a sort of shimmering, amorphous mass of mercury, forms various human and animal shapes.

Between all three movies exist some interesting moral crossovers. The Terminator (henceforth Schwarzenegger) goes from being a killer-villain in The Terminator to a father-protector in Terminator 2, and the replicator that in The Abyss is a sweet, Spielbergian messenger of peace and love is in Terminator 2 a remorseless killer called T-1000 (henceforth Patrick). Moreover, in Terminator 2 Schwarzenegger is dressed like a Hell’s Angel while Patrick is dressed like a cop. It all fits into a curious sort of mythology that seems split between Greek and Christian elements: Godlike machines ascend to earth from a hellish future to mingle with mortals; both get resurrected on various occasions, and at least one gets (metaphorically) crucified. Neither is especially meek or charitable. “Judgment day” refers to the nuclear war that wipes out three billion people in 1997, shortly after the film’s events unfold; but it’s a judgment day without any apparent deity or judge.

In the broadest terms — and by and large Terminator 2 operates only in the broadest terms, with a minimum of either plot or characters — Cameron orchestrates three basic spectacles: (1) remorseless killing and destruction based on the machines’ plowing through or eliminating anything that stands between them and their goal; (2) automatic resurrection and replenishment of the selfsame machines whenever they become mutilated, perforated, or otherwise damaged; and (3) expedient replication (by Patrick) of various humans, generally victims. All three can be said to reflect the special talents of Cameron: (1) action and violence, (2) regeneration of narrative momentum, and (3) imitation (The Terminator grew out of The Road Warrior and Blade Runner; Cameron’s 1986 Aliens grew out of Alien; The Abyss plundered everything from Disney and De Mille to Spielberg; and Terminator 2 — well, the title speaks for itself). They combine in the most beautifully tailored action sequences I’ve seen this year.

The pleasures bound up in these three spectacles are a good 85 percent of what makes Terminator 2 worth watching; significantly, they completely depend on the figures of Schwarzenegger and Patrick — high-tech machines, albeit machines designed to look like men. The remaining 15 percent depends on the only two human characters of any extended consequence, Sarah and John, and as sources of spectacle or pleasure this mother and son are paltry by comparison. Cameron works hard at making it otherwise — presenting Sarah as a fanatical and muscular guerrilla fighter and John as a rebellious, mixed-up kid in dire need of a father — but character development is virtually nonexistent, and as long as the battling machines are around, which is almost always, the humans fade into the woodwork. There’s a little bit of contrived human emotion when Sarah vengefully cracks a bone or two belonging to a nasty doctor, but really, this can’t hold a candle to the passionless mayhem routinely carried out by the machines. The question of who’s fighting for the survival of mankind and who’s fighting for the machines turns out to be secondary; as in King Kong vs. Godzilla, it’s the big lugs who matter — suffering humanity is just there for decoration.

Cameron is shrewd enough to be aware of this imbalance — he even has Sarah mordantly remark in her offscreen narration that Schwarzenegger is the best father around for John (“In an insane world, it was the best choice”) — but not shrewd enough to transcend the problem. While he tries to derive some emotional force from the theme of motherhood — a theme that carried considerable weight in Aliens and The Abyss — he doesn’t get very far with it. At a couple of climactic junctures, he even assigns unmotivated human gestures to the dueling machines — a bit of saucy finger-wagging from Patrick, a wisecrack (“I need a vacation”) from Schwarzenegger — that violate whatever status they have as characters for the sake of easy laughs. He also awkwardly strives to wring a few drops of old-fashioned sentiment from the fact that Schwarzenegger doesn’t understand why humans cry, which stretches credibility almost as much. The brutal fact of the matter is that, though Sarah and John do act honorably and ingeniously on occasion, they seem emotionally confused and ineffectual much of the time; and however much Cameron insists on giving his machines faint glimmers of humanity, they command our full respect and loving attention only when they behave like thugs.

Indeed, probably the only time Cameron succeeds in humanizing the action is when he establishes that Schwarzenegger will do anything John tells him to. In fairy-tale terms, this effectively turns Schwarzenegger into a sort of genie like the one serving Sabu in Michael Powell’s The Thief of Bagdad — and forces 12-year-old John to teach himself rudimentary morality via Schwarzenegger in order to harness his own power. “You just can’t go around killing people,” he chides Schwarzenegger at one point, who responds by asking “Why?”

Why, indeed? If Schwarzenegger and Patrick didn’t kill a lot of people and didn’t look like people themselves, we wouldn’t care a fraction as much about what they did. The functions of the two machines as relentless and remorseless killer-destroyers are chiefly what makes them live and thrive on the screen. The principle even operates in small ways: when John needs a quarter to use a pay phone, Schwarzenegger obligingly smashes the bottom of the phone with his fist so that a jackpot of change splatters out.

Terminators are fun because we’d all like to have one of our own. Caught in a traffic jam? If your Terminator is at the wheel, he’ll helpfully plow through any vehicles or motorists who stand in your way. Do you want something you can’t afford? The Terminator will grab it for you, hand it over, and not even ask for a tip. Do you want to mangle a bully who’s pestering you, or maybe wipe out someone who just irritates you slightly?

Better yet, why not go after a ruthless dictator — too bad about the legions of innocent bystanders. The possibilities are clearly endless, and as long as we have amoral machines carrying out the dirty work for us, armed with snazzy war toys and state-of-the-art programming, we can watch them work their wonders with a mixture of admiration, envy, pride, and relief, delighting in the special effects and taking care not to linger too long over any of the resulting wreckage, slow deaths, and corpses. It must be conceded, however, that Cameron’s mise en scene surpasses that of the TV news. Not even Schwarzkopf can hold a candle to Schwarzenegger when it comes to embodying our ultimate hopes and dreams.

Postscript (January 8, 2012, 22 years later): Film critic Noel Vera (Critic After Dark) has just written the following to me on Facebook:

Read your Terminator 2 piece. Good stuff, and good point about the killing (reduced to mayhem here) being the only thing we care about from the two main characters.

A few things tho–the idea for The Terminator comes mainly not from Blade Runner or even Harlan Ellison (despite what his lawyer says) but from Philip K. Dick’s two short stories: Second Variety and Jon’s World. Cameron was working at Hemdale trying to get his movie going when the scriptwriter was working on adapting the two stories for the production that eventually became Screamers (1995). The idea of a killing machine designed to infiltrate society and imitate humans–that’s a Dickian idea.

And for all of Schwarzenegger’s muscles, I submit that the single most frightening entity in the picture was Linda Hamilton, who displayed awesome muscles, especially in the first part. When the Guvernator takes over, of course, her role falls by the wayside, and it’s macho mayhem all the way.

And finally, for all of Cameron’s talent, this was the film where gigantism started taking over; Sam Raimi’s Darkman came out about the same time, and the helicopter chase scene through the LA freeways there was much more nimble and inventive.