From the Chicago Reader (June 21, 1991). — J.R.

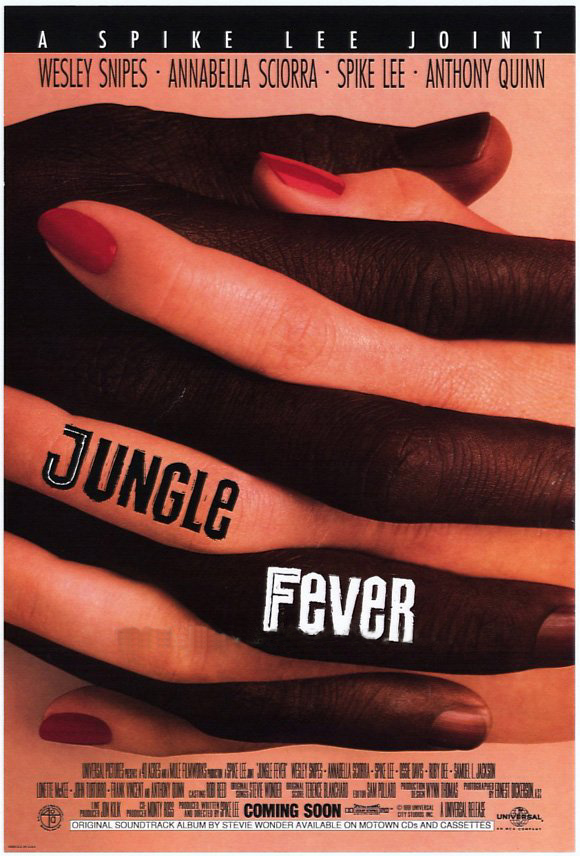

JUNGLE FEVER

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Spike Lee

With Wesley Snipes, Annabella Sciorra, Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Lonette McKee, John Turturro, Frank Vincent, and Anthony Quinn.

Trusting to luck means listening to voices. — Jean-Luc Godard in the 1960s

Compared to Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever is inspired overreaching, an exciting mess — and conceivably even more important. If the earlier movie somehow marshaled its sprawling elements into a single story in a single setting with a single theme, this one has two settings (Harlem and Bensonhurst), three plot lines, and at least four themes (interracial romance, breaking away from one’s family, crack addiction, and corporate advancement for blacks), all of which are crammed together more willfully than logically, yielding a misshapen story that is neither singular nor plural in focus, but somewhere obscurely in between.

First plot: Flipper (Wesley Snipes), an upscale Afro-American architect with a wife and daughter living in Harlem, starts an affair with his new temp secretary, Angie (Annabella Sciorra), a single Italian American who lives with her working-class father and brothers in Bensonhurst. Flipper tells his best friend Cyrus (Spike Lee), who tells his wife (Veronica Webb), who tells Flipper’s wife, Drew (Lonette McKee), who responds by throwing Flipper out. He goes to stay with his parents (Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee), and after Angie is brutally beaten by her father (Frank Vincent), she and Flipper move into a loft. Eventually he decides to call it quits with her, and she doesn’t object. Meanwhile, Angie’s former boyfriend, Paulie (a lovely performance by John Turturro), who lives in Bensonhurst with his father (Anthony Quinn) and runs his candy store, develops a crush on a black woman (Tyra Ferrell) in the neighborhood and persuades her to go out with him, despite the violent objections of his father and other Italian Americans in the neighborhood.

Second plot: Flipper’s older brother, Gator (Samuel L. Jackson), is a Harlem crackhead who keeps asking his mother and Flipper for handouts to support his habit and hangs out with another crackhead named Vivian (Halle Berry). His father, a rigid Baptist preacher who has lost his pulpit, has already banished and disowned him, but Gator manages to sneak in periodically to see his mother . . .

Third plot: Before he leaves his wife and daughter, Flipper asks his white bosses to make him a partner in their firm. He resigns when they refuse and announces that he’ll start a company of his own.

The various themes overlap in these plots and settings, but they never can be said to converge. The theme of corporate advancement for blacks is also never fully articulated — we aren’t given enough information to evaluate either Flipper’s request to become a partner or his bosses’ refusal — and it appears to be discarded halfway through the film; we never hear anything more about Flipper starting his own business.

A few stray details help link some of the plots and themes, at least by implication. Flipper’s last name is Purify, and connections certainly can be made between his notions of racial purity and his father’s. (One might also note a connection between the rigid — i.e., “pure” — stances of Flipper and his father, and deduce that the Good Reverend Doctor Purify may have lost his church for reasons comparable to the reasons Flipper lost his job.) But it’s harder to link Gator Purify with his brother and father on the basis of this shared name, unless one sees his self-acknowledged identity as a crackhead as either a reaction to his father and brother or as an existentially “pure” form of self-negation. Otherwise, the plots and themes simply coexist without merging.

Most irritating of all, Lee has shamelessly echoed the symmetrical framing devices used in Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues to begin and end this movie — with matching crane shots to establish a neighborhood, and matching lines and behavior to establish the situation of the characters — which brings a false sense of unity and closure to a movie that actively resists both. It’s the equivalent of a veteran jazz musician summoning up an old riff to round off a daring chorus when he suddenly runs out of gas, and even though it performs the expedient function of winding things up, it can’t disguise the fact that a lot of plot strands are still hanging.

Why, then, do I regard Jungle Fever as a major step forward — not only for Spike Lee, but also for American movies in general? Because he may be creating a new kind of commercial American movie in the process of trying to cram everything in — a kind of “living newspaper” where front-page stories exist in proximity to one another without necessarily linking up, and where it’s left to the audience to make some of the vital connections (or not, as the case may be). Lee’s outsized ambitions and impatience, which lead to all the problems cited above, are straining the limits of conventional story telling and moviemaking — forcing Lee and his audience into fertile new areas, some of which may even lie beyond the conscious wishes of both. And Lee has been gaining enough mastery in other areas — above all, in directing actors and writing or generating dialogue — to be able to shoot off in several directions at once without losing any of his control or momentum. With a running time of well over two hours, Jungle Fever moves so feverishly from first shot to last that one never has a chance to be even momentarily bored or distracted; despite all the leapfrogging between themes, characters, and neighborhoods, it looked even better and seemed even shorter the second time I saw it.

Yet at times the experience is a little bit like being caught in a flood. To compound the general sense of surfeit and confusion, Lee has overloaded his sound track with more music than ever before, much of it vocal. It’s a relief to see him finally working with a composer other than his father Bill Lee, whose scoring skills have always struck me as questionable; the original music here was written by Stevie Wonder and Terence Blanchard, and it’s the best score for a Spike Lee film to date. But given how strong the film is without the music, Lee’s insistence on using it in practically every scene — featuring a 71-piece orchestra and the 49 voices of the Boys Choir of Harlem, and 23 new and old songs, including 3 by Frank Sinatra, 3 by Mahalia Jackson, and 13 by Wonder — is sometimes a bewildering belt-and-suspenders procedure. It’s as if he didn’t trust his material enough to allow it to speak for itself, but had to constantly juice it up to symphonic proportions.

Occasionally the music is used for ironic undercutting; when Angie is being beaten by her father for sleeping with Flipper, Wonder is singing, “This was the last time I heard her saying, ‘Mother, Father, I love you . . . ‘” Sometimes it’s used for ethnic underlining: all the Sinatra is heard in the Bensonhurst candy store operated by Paulie, and all the Mahalia Jackson is played by Flipper and Gator’s father in his Harlem apartment. But sometimes it’s just unnecessary noise: Flipper’s wife Drew is throwing all his papers out the window and into the street, causing a noisy crowd to gather around Flipper, and he and Drew are screaming at one another — but Lee evidently figured this wasn’t enough to listen to, so he added a rap number with a backup chorus. Perhaps significantly, my two favorite scenes in the picture — a “war council” consisting of Drew bitching with several of her black friends, and a violent confrontation between Paulie and some Italian regulars in his candy store — are just about the only ones that do without music entirely.

One key to what’s going on in this maelstrom is the multiplicity of voices. Critic Bill Krohn has provocatively described Do the Right Thing as a conflict of discourses, linking it to the debates between French Maoists and French communist party members in Godard’s La chinoise (1967). In a variety of ways, Jungle Fever goes even further in suggesting an American mainstream equivalent to Godard’s work in the mid-60s — less intellectual, but equally attuned to a newspaperlike currency and immediacy. Significantly, both directors have drawn much of their material from news stories. Jungle Fever opens with a dedication “in memory of Yusef K. Hawkins, August 23, 1989,” and Lee has reported that one of the film’s incidents was inspired by Marvin Gaye Sr. shooting Marvin Gaye Jr. There are also, among many other news references, allusions to New York’s last mayoral election and its ethnic ramifications and to the rap song created by one of the black rapists of the Central Park jogger.

Both filmmakers splinter their narratives into disassociated parts, some more “finished” and fully articulated than others. Both switch stylistic gears at periodic intervals, specialize in intertextual references (the same white cops who killed Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing turn up here to terrorize Flipper and Angie), and typically stage their dramas in terms of political and cultural confrontations.

Even more to the point, both Godard and Lee create all sorts of occasions and excuses for multiplying their uses of on-screen and offscreen verbiage, usually in unorthodox and innovative ways. Godard often has characters reading aloud or quoting from texts, and Lee seems equally compulsive about playing song lyrics over or under dialogue. Both seek out diverse ways of presenting words visually. (A few examples in Jungle Fever: jokey and thematically relevant street signs in the opening credits and printed song lyrics in the closing credits, both of which slide across the screen at oblique angles; inserted shots of maps with place-names to identify Harlem and Bensonhurst; a real New York Post headline, “Doin’ the Right Thing,” inserted as another intertextual reference in a scene in the candy store.)

In striking contrast to Lee’s profile as an angry media spokesman, projecting attitude at almost every turn, this movie speaks with lots of tongues, many of them divergent and contradictory. Some of these voices bear a strong resemblance to that of Lee’s public persona, but the other voices challenge or qualify what he says in interviews, placing them in a different social and political context. If these voices can be said to converge momentarily — emotionally rather than conceptually — this occurs only in the final scene, when Flipper screams in pain, “No!” It calls to mind the tribute paid to Herman Melville by Nathaniel Hawthorne: “He says No! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes.” Otherwise, what Lee is saying and what his movie is saying remain distinctly separate. (Significantly, his character in this movie is once again — as in Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues — someone who plays the role of dramatic catalyst rather than spokesman for the film’s positions.)

Much of the same disparity between Lee’s utterances and his film’s could be felt when Do the Right Thing came out. Lee — understandably recoiling from the paranoid charges of certain critics that his movie was irresponsible because it would foster race riots — started to give increasing prominence to Malcolm X’s statements about violence over Martin Luther King’s in his interviews about the movie. But the movie’s statement was considerably more nuanced and multifaceted — and more evenly balanced between King’s and Malcolm’s positions. And while some of Lee’s recent statements about Jungle Fever suggest a separatist bias regarding interracial romance — a bias stated by most of the Harlem and Bensonhurst characters in the film — the movie itself is a good deal more open and ambiguous.

Even Lee has acknowledged that the second interracial couple posited toward the end of the film, Paulie and Orin, have a much better chance of succeeding than the first because their relationship is predicated on more than just racial myths and curiosity. (The fact that Paulie and Orin both live in Bensonhurst is also clearly a contributing factor; a regionalist to the core, Lee thinks so much in terms of New York neighborhoods that one wonders how he’ll deal with the geographical spread of The Autobiography of Malcolm X in his next picture.)

More specifically, some of Lee’s recent interviews strongly suggest that he’s been listening with profit to his actors. There was some commentary in the press about his conceptual differences with Danny Aiello regarding Sal’s character in Do the Right Thing — differences that to all appearances wound up broadening the picture’s viewpoint. Recently we’ve heard about conceptual differences with Annabella Sciorra on Jungle Fever that seem to have had a comparably beneficial effect. (Sciorra didn’t want her character’s involvement with Flipper to be motivated exclusively by sexual curiosity, and Angie’s character is sufficiently ambiguous on this score to throw some doubt on Lee’s original hypothesis. Both Sciorra and Snipes insisted on charting the mutual attraction of their characters over several take-out meals, while Lee originally wanted them to dive into sex at the first opportunity.) Still another example — and an especially telling one — is the wonderful “war council” scene, which was partially improvised by the actresses and clearly gains from their creative input. Indeed, if this movie shows a clear advance on Lee’s part in dealing with female characters, this is very much a matter of “listening to voices.”

So far I’ve said very little about the film’s content — mainly because it seems impossible to do so without first acknowledging the forms — and the forms of addressing the spectator — that this content takes. On the subject of race, Jungle Fever might be said to synthesize some of the concerns of School Daze (divisions within the black community on the basis of skin color and class) and some of the concerns of Do the Right Thing (divisions within a multiracial community on the basis of skin color and class). Thus Drew’s light skin and mixed parentage (we learn in one scene that she has a white father) and dark-skinned Italians play roles in the constellation of identities and attitudes that are established.

Lee’s position within this constellation seems closely allied to Flipper’s — that is, the position of someone who identifies himself as black and agitates for black rights, but who finds himself working professionally in and (to some extent) for a world that is perceived mainly as white. It’s a position rife with built-in contradictions, and it might be argued that the tendency of Jungle Fever to speak in many voices, creating a cacophony of discourses, grows directly out of these contradictions, which stem more from American society than from the efforts of an ambitious black man to make his way in such a world. In any case, Flipper’s racial position and that of the film are far from identical; it is even possible to conclude that Angie is less of a racist than Flipper is, if only because she appears to be much less concerned with questions of race.

The logistics of their separate positions in relation to society at large aren’t ignored, however. Angie may be more physically vulnerable to racist attitudes in Bensonhurst than Flipper is in Harlem, but when it comes to neutral territory, she has a distinct advantage. The location of Flipper and Angie’s loft isn’t specified, but we’re led to assume that it’s somewhere in Manhattan other than Harlem. When Flipper is threatened at gunpoint by two white cops outside this loft — an incident provoked by the couple playfully sparring on the street — it is Angie, not Flipper, who explains that they’re lovers and who angrily showers abuse on the cops. Flipper is so terrified that he immediately concocts a cover story: “I was just making sure she was getting home safe.” And after the cops leave, he berates her for her candor: “What are you doing telling ’em we’re lovers? You wanta get me killed?” It appears to be this incident more than anything else that provokes him into ending their affair.

On the subject of crack addiction, Jungle Fever offers no debate or analysis, merely an anguished look at what it is doing to people, culminating in a large-scale and deliberately exaggerated (Lee describes it as “surrealist”) scene set in a fictional Harlem crack house called the Taj Mahal. Lee has argued that he excluded drugs from Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues because they didn’t belong there, and given the more concentrated agendas of those films, it is easy to see what he means. Certainly Samuel J. Jackson’s extraordinary performance as Gator, which won a well-deserved special prize at Cannes, is more than enough justification for broaching the subject here, though its thematic connection with the rest of the movie is restricted mainly to the matter of becoming alienated from one’s family.

The theme of Flipper starting his own business is clearly a carryover of a theme that played an important role in Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues — the problem of working for the Man and what this means in terms of black self-determination. If Jungle Fever doesn’t get around to resolving this issue, it may be because Lee himself understandably hasn’t found a way of fully resolving it in his own career.

If there’s a limitation to Lee’s use of multiple voices in his filmmaking, it may be his schematic insistence on defining and juxtaposing characters almost exclusively according to castes, classes, and neighborhoods. (In the college world of School Daze fraternities and sororities took the place of neighborhoods.) The overall pessimism of Jungle Fever has a lot to do with the incapacity of most of its characters — Angie, Paulie, and Orin may be partial exceptions — to stray too far from their own turfs, either physically or mentally. (The name “Flipper” suggests a desire to pass from one world to another, but significantly this is perceived in either/or terms rather than as a desire to go anywhere at all.) It could be argued that this localized vision has a lot to do with the experience of native New Yorkers, and however much this vision may serve to give form to the conflicts of Do the Right Thing and Jungle Fever, it also implies a certain incapacity to think beyond them that may affect Lee along with most of his characters.

One of the most striking innovations in the movie, employed twice, is a stylized, frontal low-angle shot of two characters apparently walking down a sidewalk; although we faintly hear the sound of offscreen footsteps, the characters actually appear to be carried along on a sort of conveyor belt without walking at all, the tops of trees drifting past them in a dreamlike flux. The first time this happens, it’s with Angie and Paulie in Bensonhurst; the second time, it’s with Flipper and Cyrus in Harlem. In both cases this conveys the comfort of moving with a compatriot through a cozy world where identity and familiar surroundings are firmly in place — a sort of womblike oasis within a larger jungle that is raging with fever and pestilence.

Assuming that Lee can — or should — position himself outside this oasis and continue to function, there’s no telling what he might accomplish. Do the Right Thing was full of promise, but Jungle Fever is something more — a movie by a master director with a voice of his own who is still interested in discovering what he has to say, and who is brave enough to let others help him find it. As long as Lee keeps listening to the right voices, we have a lot to look forward to.