From the May 10, 1991 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

SPARTACUS

*** (A must-see)

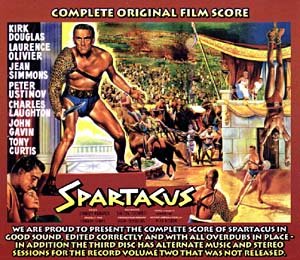

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Written by Dalton Trumbo

With Kirk Douglas, Jean Simmons, Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Peter Ustinov, John Gavin, and John Ireland.

“It has acres of dead people, more blood and gore than you ever saw in your whole life.

“In the final scene, Spartacus’s mistress, carrying her illegitimate baby, passes along the Appian Way with 6,000 crucified men on crosses.

“That story was sold to Universal from a book written by a Commie and the screen script was written by a Commie, so don’t go to see it.”

Despite these dire warnings from gossip columnist Hedda Hopper — and another from the American Legion, which sent a letter to its 17,000 local posts urging people to boycott the movie — Spartacus, released in 1960 and reportedly the most expensive movie ever shot in Hollywood, eventually turned a profit. It was even the top money-maker of 1962 after it went into general release — thereby, I suppose, making Commie symps of all of us who went to see it. It was the Kennedy era, and the blood and gore on view were pretty tame by today’s standards; for the record, the number of crucified men — rebel slaves — while high, is a good bit shy of 6,000.

It’s true, however, that the baby is illegitimate, and that the script was written by a former Communist, Dalton Trumbo, adapting a best-selling novel by another former Communist, Howard Fast. The fact that Trumbo scripted Spartacus was unexceptional; under assumed names, he had scripted a good many movies for reduced fees during the Hollywood blacklist — unlike most of his fellow victims, whose careers went by the wayside — and four years earlier he’d even written a script (for The Brave One) that won an Oscar no one could collect. What was exceptional — and infuriating to Hopper, the American Legion, and others — was that Spartacus gave him screen credit.

A blockbuster epic that might be described even in its newly restored form as a wonderful mess — uneven but often exciting and emotionally stirring — Spartacus actually encapsulates the onset of the Kennedy era in much the way that Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments (1956) epitomized Eisenhower’s last term of office. As if to drive the point home, Kennedy even left the White House in the middle of a snowstorm in order to see it at a local theater, and praised it to reporters afterward, when he easily could have asked for a private screening.

A movie without a single auteur — perhaps to the same degree as more certifiable favorites like Casablanca and Gilda — Spartacus is the result of many conflicting egos and forces, with Universal Pictures, Trumbo, Fast, director Stanley Kubrick, and executive producer and star Kirk Douglas among the main players. The lengthiest account of its making that I’ve read can be found in The Ragman’s Son, Douglas’s 1988 autobiography, which reveals a tissue of paradoxes that seems almost paradigmatic of Hollywood. It confirms Kubrick’s earlier contention that “mine was only one of many voices to which Kirk listened,” but it also reveals that Kirk Douglas’s voice was only one of many voices to which Universal listened.

As Douglas tells it, it was Universal that insisted on hiring the first director, Anthony Mann, and Universal that insisted on firing Mann after about two weeks of shooting. (One major complaint was that Mann effectively allowed Peter Ustinov to direct his own scenes; according to Michel Ciment’s book on Kubrick the film’s opening sequence can be credited to Mann, but since Ustinov figures in this sequence he may deserve part of the credit as well.) Douglas — who had arranged the financing for and starred in Kubrick’s previous film, Paths of Glory — managed to get Kubrick hired as replacement director over a weekend, without losing a day of shooting. Shortly afterward, the leading lady, German actress Sabina Bethmann, was replaced by English actress Jean Simmons. This violated Douglas’s original scheme that all the Romans be played by English actors and all the slaves except the leading lady, a foreign slave, be played by Americans — a formula adapted from The Vikings, the previous film he produced and starred in, where English actors played English characters and Americans played Vikings.

The Vikings had been a hit, and its influence on Spartacus showed in a few other areas too: the film’s graphic gore and violence and Tony Curtis’s pivotal role. At the end of The Vikings, Douglas and Curtis fight to the death, and Douglas wins. As Douglas tells it, Curtis basically pleaded his way into Spartacus, so a role was finally created for him — “a poetic young man named Antoninus who becomes like a son to Spartacus.” At the end of Spartacus, a Roman fascist named Crassus (Laurence Olivier) who succeeds in quelling Spartacus’s slave revolt forces the two friends to fight to the death and orders the winner to be crucified.

One of the many paradoxes of this film about freedom — very loosely based on an actual slave revolt in 73 BC — is that it’s the only film Stanley Kubrick directed on which he considered himself enslaved. It seems he got on Douglas’s wrong side by asking to take full credit for Trumbo’s screenplay, a screenplay he later expressed much public disdain for. According to Douglas, it was his own anger and disgust at Kubrick’s suggestion that persuaded him to break the blacklist, rather than any independent desire to set a precedent. Later on, Trumbo submitted a critique more than 80 pages long of Kubrick’s first rough assembly of the film — Douglas calls it “the most brilliant analysis of movie-making that I have ever read” — and Kubrick was evidently required to restructure and reshoot the film on the basis of it. In the process, he won the opportunity to shoot large-scale battle scenes in Spain, which are among the most spectacular ever filmed. Like the training and revolt of the gladiators in the first part of the film, these are scenes with minimal dialogue, and probably because of this they show Kubrick’s masterful hand much more clearly and unequivocally than the other sections.

To restore the film to its original 197-minute running time, one of the scenes that alludes to Crassus’s sexual interest in Antoninus, originally suppressed by the censors, had to be redubbed because the original sound is lost — an effort that involved Anthony Hopkins speaking lines assigned to Olivier, Curtis rerecording his own lines, and new sound effects, all according to faxed instructions from Kubrick, who remained in England. It plays pretty well, although it isn’t quite as funny as the censors’ suggestions for redoing the scene in 1960. Crassus indicates his bisexuality to Antoninus by explaining that he has an appetite for snails as well as oysters, and the censors proposed that the scene might pass if “artichokes and truffles” were substituted for “snails and oysters” and the word “appetite” wasn’t used; but when the scene was reshot accordingly, the censors still wouldn’t pass it.

Is Spartacus a Commie movie? It’s true they loved it in Russia. Apart from the proliferating crucifixions at the end, Spartacus is (along with Land of the Pharaohs) the least religious of spectacles about antiquity — most of the smart characters seem to be atheists or agnostics. And the oppression of the gladiators and their subsequent revolt, which leads to the wider slave rebellion, are conceived in terms that are essentially Marxist: the ruling class sets worker against worker until they finally join forces to overthrow their masters, and Spartacus himself is the charismatic proletarian hero par excellence — humble, illiterate, even a virgin when he goes into enforced gladiator training, to slay or be slain by his brothers in oppression. (Significantly, his virginity and his bondage both end around the same time.)

One might even argue that Spartacus can be read as a Marxist allegory about the blacklist itself. Once the rebels are defeated, they’re informed by Crassus that all of them but one will be spared if they agree to identify Spartacus — “naming names” is the implicit formula. Each of them responds by declaring, “I am Spartacus,” which is why so many crucifixes wind up flanking the Appian Way — a rough approximation of the position taken by the Hollywood Ten (including Trumbo), who went to prison for refusing to name names.

But let’s not forget that Spartacus is a Hollywood movie; there’s a lot more than Marxism that confuses the relative purity of this model. Spartacus may be a charismatic proletarian hero, but he’s also a teacher and father figure who makes all the basic decisions — moral as well as practical — for the slave rebellion as a whole, so he clearly doesn’t qualify as a cell member. Before the revolt, Spartacus’s opponent in the gladiatorial arena is a noble black, played by Woody Strode, who defeats him. When, instead of killing Spartacus, he throws his triton in the general direction of the Roman spectators who are calling for a kill — and is violently killed by Crassus for this gesture — the reference to the nonviolence and humanism of the civil rights movement is unmistakable.

There are also ways in which the sheer spectacle and violence celebrated in Spartacus is more decadent and capitalist than puritanical and Marxist, and the filmmakers show flashes of awareness of this. In the events leading up to the gladiatorial matches, for instance, we’re invited to share the sadistic and sexual predilections of Crassus and his party in selecting and matching up opponents like beefcake pinups (“Oh, they’re magnificent!” squeals one of the two women); it’s only after the first fight begins that we cut to the viewpoint of Spartacus — inside a stall, peeking through the wooden slats at the combat, waiting to go on next. The opulence of Crassus’s home back in Rome (which is where the oysters-and-snails dialogue takes place) evokes a similar ambivalence; we’re clearly invited to enjoy this excess as well as disapprove of it.

There are plenty of occasions when playing out the allegory conflicts with the movie’s verisimilitude, and not even Trumbo’s most literate and witty dialogue can entirely paper over the gaps. Crassus’s inability to identify Spartacus and the acquiescence of Spartacus and Antoninus in fighting to the death at his command are only two of the more obvious examples of this. Even some of the most powerful and stirring moments in the film frequently threaten to atrophy into camp, particularly when incidental dialogue is involved; the remarkable final scene, which I blush to admit brought tears to my eyes, is nearly destroyed by a Roman guard intoning, just like an American cop on the beat, “Don’t the lady know there’s no loitering allowed?”

Given all the warring creative and administrative forces, as well as the $12 million, that went into Spartacus, it isn’t surprising that the film is all over the place — in anticipated demographic appeal as well as narrative focus. I should stress that my spotty summary omits many subplots, the most interesting of which involves the wily political machinations of a Roman senator named Gracchus (Charles Laughton) — a liberal martyr in disguise, as it turns out. Although Ustinov won an Oscar as an obsequious slave trader, Laughton’s juicy ham provides the best performance. Critic Simon Callow has written an interesting comparison between Laughton’s Gracchus and Olivier’s Crassus as active screen presences:

“[Crassus’s] glacial patrician manner, his ruthless ambition, his strong desire for his handsome young slave, are all cleanly and sharply indicated; it is as if there were a thin black line drawn around the role. Laughton’s Gracchus has no such boundaries, no such definition. It spreads, floats, expands, contracts. The whole massive expanse of flesh seems to be filled with mind–thoughts are conceived, born and die in different parts of that far-flung empire. Sedentary for the most part, Gracchus seethes with potential movement. He is a jelly that has escaped the mould; Olivier’s (and Crassus’s) sharp knife can gain no purchase on it.”

At the other end of the scale, Tony Curtis and John Ireland as slaves and John Dall and Nina Foch as Romans are pretty awful, and the banal movie-star gloss of their performances periodically undermines some of the film’s best claims to be taken seriously. The film’s nadir is a scene in which Curtis recites a poetic “song” to a group around a campfire and which becomes the occasion for a montage devoted to the beauties of a kitschy soundstage version of “nature,” followed by glimpses of other salt-of-the-earth slaves at rest who register like warmed-over Depression archetypes.

Just as the Kennedy administration revivified a few socialist homilies from the 30s by dressing them in youthful, upscale garb (the Peace Corps, say, as a gentrified variation of the WPA), Spartacus dilutes and distorts its intermittent Marxism with all the gaudy and fruity colors of the Hollywood rainbow. But it still has some ideological coherence as a liberal expression of its period, and therefore a unity and power — above all, a noble kind of sincerity — that not even its occasional aesthetic incoherence can undermine. Taking all its flaws into account, I still find it one hell of a show.