As I recall, this article, published in the November 2, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader, had two immediate consequences for me. The first was that the late Gene Siskel, an acquaintance of mine from press screenings, refused to speak to me for several years, and I was no longer able to attend any more press screenings in Chicago held mainly for him and Roger Ebert. The second was that on November 11, when Rouch appeared at the Film Center, he publicly thanked me for my article, which I don’t believe had ever happened to me before with a filmmaker. So one might say that I lost an acquaintance (at least until Gene decided to forgive me several years later, after I attended a tribute to him and Roger at the Music Box) and gained a friend. —J.R.

LES MAÎTRES FOUS

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Rouch.

THE LION HUNTERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jean Rouch

With Tahirou Koro, Wangari Moussa, Belebia Hamadou, Ausseini Dembo, Sidiko Ko ro, and Ali the apprentice.

JAGUAR

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Rouch

With Damoure Zika, Lam Ibrahim Dia, and Illo Gaoudel.

Anthropologists of the year 2090 — if humanity still exists and is still sufficiently divided, sufficiently colonialist and hierarchical, to need anthropologists — may look with wonder at that revealing artifact of late-20th-century multinational capitalism, the American newspaper. A specialized form of sales catalog that doesn’t always list prices but nonetheless reflects the current market value of a wide variety of cultural objects, institutions, and ritual practices, including countries, wars, companies, and government and business policies as well as books, records, and movies, it reveals at a glance the priorities that such a culture places on its own products, activities, and commentators.

A look at the Friday section of the Chicago Tribune of October 26, for instance, reveals, along with ads, the following items, which seem to appear in descending order of importance. (1) A pejorative review of a very bad movie by a famous amateur reviewer, Gene Siskel, whose “expertise” is largely predicated on his lack of knowledge about and lack of interest in film history. (2) Five more reviews of disposable movies by teenage reviewers whose own “expertise” is clearly gauged by the degree to which they qualify as budding Siskels. (3) Two more pejorative reviews of very bad movies (including the same one knocked by Siskel) by a professional reviewer, Dave Kehr, whose professionalism is largely predicated on his knowledge about and interest in film history. (4) Two more reviews by Kehr of much more important movies, including Charles Burnett’s To Sleep With Anger, which Kehr plausibly deems a “great film,” a movie “that can stand confidently with Renoir’s [Boudu Saved From Drowning],” and which Siskel hasn’t even bothered to cover in a capsule review.

It’s safe to predict that in this week’s and next week’s Friday you won’t find any extended treatment of three exciting classic films by French anthropologist Jean Rouch — Les maîtres fous, The Lion Hunters, and Jaguar — showing at the Film Center on November 4 and 11, because their market value is absolutely nil. All three were made between the 1950s and the early 1970s, and the fact that Rouch, the greatest living anthropological filmmaker, will be flying from Paris to Chicago in order to introduce and discuss the first two films on the 11th can’t be deemed very important either — at least not as important as the awfulness of such routine stinkers as Sibling Rivalry, Marked for Death, and The Man Inside, much less the brilliance and power of To Sleep With Anger. So even considering going to see these Rouch films means agreeing to step outside of official history — and not only the history of commercial movies, but the traditional history of ethnographic filmmaking as well.

By rough estimate, Rouch has made well over 100 films since the late 1940s; it’s hard to be more precise because the most up-to-date Rouch filmography I can find is 11 years old. Most of these films are ethnographic shorts that have never shown in the United States, either publicly or privately. But some, including half of the eight that I’ve managed to see myself, are semifictional features that bear some relation to ethnographic work without fitting fully or comfortably into that category.

Rouch’s first feature, Moi, un noir (Me, a Black Man, 1957) — focuses on three young men from Niger who work as casual laborers in Abidjan. They re-create their own lives and fantasies in front of Rouch’s camera, and one of them fancifully narrates the silent footage. All three assign themselves fictional movie names — Edward G. Robinson, Tarzan, and Eddie Constantine. (A woman in the story calls herself Dorothy Lamour.) La pyramide humaine (The Human Pyramid, 1959), a Rouch feature I haven’t seen, was selected in 1965 as one of the ten greatest postwar French films by seven Cahiers du Cinéma critics, among them Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer. This fiction film about the segregation at a real high school in Abidjan is a sort of psychodrama featuring actual students. (In fact, the separate racial groups at the school had very little to do with one another until the film brought them together.) Needless to say, both of these early features were widely banned in Africa, and for all practical purposes, in the United States as well; neither, to the best of my knowledge, has ever been subtitled in English.

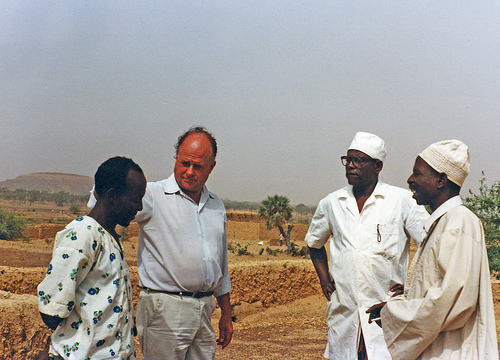

Born in 1917, the son of a naval officer who was one of the earliest explorers of the South Pole, Rouch trained as a civil engineer and then went to work in Niger and Dakar. After the war, he studied anthropology at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris and then returned to Niger, where he made his first ethnographic shorts in the late 1940s. He first came to international attention with Les maîtres fous (The Mad Masters, 1955), a 35-minute film made at the request of Hauka priests and initiates — a persecuted group of workers, some of them from the Upper Niger, who wanted a record of their annual ceremony.

The film begins and ends with footage of these priests and initiates in Accra — today the capital of independent Ghana, then a port city in the British colony of the Gold Coast — working as stevedores and in such comparable jobs as washing bottles and digging ditches. Once the priests and initiates leave for the country, the film becomes a fairly straightforward account of their rituals: the nomination of a new member, public confessions by the penitents, the sacrifice of a chicken, and then the trancelike “possession” of the penitents — which includes music and dancing, a man burning himself with fire, some participants foaming at the mouth, and the eventual sacrifice of a dog, the drinking of dog blood, and the brewing and consumption of dog soup.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of this complex and hair-raising event is the way the participants and the settings take on theatrical roles — the oppressed re-enact their own oppression, taking the parts of their colonial oppressors. So we see “the governor’s palace,” the “British governor” and his “sentries” (complete with make- believe rifles), “the Judge,” “the General,” and so on. For this reason, among others, the film was banned throughout the British colonies in Africa, and it exerted a major influence on Jean Genet when he came to write his play The Blacks a year or two later.

Rouch himself narrates in English, and the occasional awkwardness of his phrasing and pronunciation — “riffles” for “rifles,” for instance — helps to isolate this film from the pseudo- objectivity of conventional documentaries of the kind generally shown on PBS, in which the faceless and supposedly “neutral” voice-of-God narration is supposed to provide a transparent window on the action. But even without Rouch’s accent — which is, of course, apparent only in the English version being shown here — the editing, commentary, and structure already remove this film somewhat from the allegedly scientific stance that ethnographic documentaries are supposed to assume. At one point, Rouch cuts directly from the Hauka ceremony to the real British governor and his troops in Accra performing “the trooping of the colors”; he notes on the sound track that “if the order is different here from there, the protocol remains the same.” Later, when the participants return to work in Accra, Rouch explains in some detail what each of them does in daily life: the “general” is actually a private; many of the penitents dig ditches; some work at a mental hospital; one is a pickpocket.

It’s worth noting that while La chasse au lion à l’arc (The Lion Hunters, 1965) and Jaguar (1967) were completed and released much later than Les maîtres fous, they were all shot more or less concurrently — The Lion Hunters between 1957 and 1965, Jaguar between 1954 and 1967. (The opening shot of Les maîtres fous –an African pedestrian waiting for a train to pass so he can cross the street — recurs in a very different context in the middle of Jaguar.) The Lion Hunters, a fascinating account of lion hunting on the border between Niger and Mali (apparently the same area reached in last year’s commercial film The Mountains of the Moon) is the most conventionally ethnographic of the three films. Jaguar is the least conventionally ethnographic, closer to the methods of Moi, un noir and La pyramide humaine. This semifictional story of three young men who leave Niger for work on the Gold Coast is narrated by the young men themselves, with a few explanatory remarks from Rouch, as we follow their shared and individual experiences. To complicate matters, both The Lion Hunters and Jaguar have been reworked by Rouch over the years into several separate versions with different running times: The Lion Hunters, which is 68 minutes long in the version showing here, also has 75- and 88-minute versions, while Jaguar has been successively shortened over the years from 150 minutes to 110 to 93.

The Lion Hunters has an English narration spoken by someone other than Rouch, which emphasizes its relatively impersonal aspect. But the role of narrator as storyteller is still evoked — his first word is “Listen…” — and at one climactic point in the hunt, the film dramatizes the camera’s presence in the most forcible way possible. When a shepherd is suddenly attacked and badly injured by a lion, the image abruptly freezes, and the narrator, speaking for Rouch, says, “I stopped filming” — although the sound person continued to record the event, as we can hear. This is the only point in the film when the narration shifts to first person singular (there are previous uses of “we”), and it points to Rouch’s own sense of responsibility about the people he is filming. (He later said that if the man had died, he never would have shown the film at all.) The issue of representation is also broached, more generally, in the story line itself: after the hunters return to their village, they re-enact the hunt for their neighbors in a highly theatrical manner, with one of them playing the lion and a child enlisted to play the bush that the lion is trapped in; and the film ends with a performance of the “song of the hunters” while the story of the hunt is told to children.

Jaguar also reflects on representation — three young Nigerians tell their own story — although here the veracity of the story is clearly in doubt, for several reasons. For one thing, school dropout and ladies’ man Damoure Zika, cattle herdsman Lam Ibrahim Dia, and apprentice fisherman Illo Gaoudel are recounting many of their adventures and even various conversations a year or two after they allegedly took place (which was shortly before Ghana became independent), improvising their commentaries over silent footage that was mainly shot during the colonial period. (Part of what they encounter in Accra are prerevolutionary communist rallies.) For another thing, in the film proper, after they decide to follow the advice of a fortune-teller and split up at a crossroads in order to travel to the Gold Coast separately, the crosscutting between their separate stories suggests that they’re happening concurrently; but they obviously can’t be, because Rouch himself is following and filming all three men. (The jaguar of the title, incidentally, refers not to the animal but to West African slang for “city slicker.”) Eventually, in a move that seems linked to Ghana’s independence, the three friends link up again and start their own business, called “Petit à Petit,” from the proverb, “Little by little the bird makes his bonnet — the bonnet being the turban of a chief.

Dedicated to the memory of French actor Gerard Philipe, who gave Rouch the money he needed to complete the film, Jaguar has in fact been described by Rouch as “pure fiction” and “a postcard in the service of the imaginary.” He has compared it to Surrealist painting — “using the realest possible [methods] of reproduction…in the service of the unreal, putting them in the presence of irrational elements.” To me, however, the charming and rambling aspects of the narrative are a good deal closer to music than to painting — and to the kind of music that takes you places. There’s even a relevant connection here to performance art.

In all the Rouch films I’ve seen there’s a contradiction between the supposedly impartial stance of the documenting anthropologist and the personal style and vision of an auteur. Rouch is a pioneer in that branch of filmmaking known misleadingly as “cinéma vérité,” and somewhat more lucidly as “cinéma direct” — making use of lightweight and portable cameras, which he generally mans himself, and sound equipment; and as soon as the technology permitted it, of sync sound and extended takes. But his personal relationships to what he is filming, his frequent use of his subjects as creative and artistic collaborators, and his impulse to become a storyteller rather than a dry recorder of “facts” have all placed him at the forefront of French narrative cinema.

In 1968, Jacques Rivette observed that “Rouch is the force behind all French cinema of the past ten years, although few people realize it. Jean-Luc Godard came from Rouch. In a way, Rouch is more important than Godard in the evolution of French cinema. Godard goes in a direction that is only valid for himself, which doesn’t set an example, in my opinion. Whereas all Rouch’s films are exemplary, even those where he failed . . . ” Several years later, Rivette cited Rouch’s original 8-hour cut of Petit à Petit — his sequel to Jaguar, featuring the same characters more than ten years later — as “the main impulse” behind his own monumental 13-hour serial Out 1. In fact offscreen narration, fiction merging ambiguously with documentary, extended narratives expanding in every possible direction, and the notion of the filmmaker as shaman as well as witness and participant are only four of the many devices and ideas Rouch pioneered that were appropriated by the French New Wave.

In one of his essays Rouch answers the perennial question “For whom do you make your films?” First, he says, he makes them for himself; second, for the people he films; and finally, “for the greatest number of people possible, for all audiences.”

The first answer is one any conventional ethnographic filmmaker might have given, since ethnographic films are commonly regarded as “notebooks,” everyday tools of the trade — although even here Rouch departs from orthodoxy when he coins the term “ciné-trance” to describe his own state when filming, deciding what he should or shouldn’t record. But the other two answers seem to place Rouch in a different camp. Significantly, in a 1965 interview, Claude Levi-Strauss expressed approval of Rouch’s ethnographic films and disapproval of such films as Moi, un noir and La pyramide humaine; for him, the latter were the equivalents of an ethnographer publishing his own notebooks — for Levi-Strauss, it would seem, a breach of professional etiquette.

Rouch’s oft-repeated goal is to achieve a kind of “shared anthropology” through the means of a “participant camera” — acknowledging that the camera’s very presence alters whatever he films, but at the same time striving to put cinema at the service of his subjects and not merely at the service of anthropologists. In the 105-minute version of Petit à Petit (1969), this notion of “shared anthropology” is pursued both literally and comically when Damoure Zika flies to Paris to study the peculiar tribal habits of the French, and even stops random pedestrians on the street to measure the sizes and shapes of their heads. (It’s every bit as delightful as Jaguar, and I’m at a loss to explain why it has never been distributed in the United States.)

But for contemporary ideological opponents of anthropology, such as writer and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha, who cannot fully extricate anthropology from colonialist assumptions and practices, it is impossible to conceive of even a “shared anthropology” without vestiges of paternalism (or maternalism). From this standpoint, Rouch can be regarded only as a liberal-humanist apologist for anthropology, not as a filmmaker who offers any radical alternative to it. Furthermore, though we’re occasionally aware of the camera in The Lion Hunters, the absence of visible white people might be said to falsify some of our overall impressions — invalidate our sense at times that we are unmediated witnesses of arcane tribal practices.

But it might also be argued that Rouch has used this problematic stance as a means of replenishing and broadening the possibilities of both story telling and performance on film, a notion some of his boldest experiments suggest. In Chronicle of a Summer (1960), which he directed with sociologist Edgar Morin, a group of Parisians are interviewed about the quality of their lives, then asked to comment on those interviews after seeing them several months later. In Gare du Nord — Rouch’s scripted fictional contribution to the 1964 New Wave anthology feature Paris vu par…, a sketch that anticipates Rob Tregenza’s Talking to Strangers (1988) — he records a quarrel between a husband (played by Barbet Schroeder, the director of Reversal of Fortune) and wife, the wife’s departure, her meeting with a stranger who invites her to run away with him, her refusal to do so, and the stranger’s suicide. All this happens in two consecutive and uninterrupted ten-minute takes — an unsettling adventure in the act of filmmaking itself that pushes the resources of “cinéma direct” to its limits.

Even in the more conventionally ethnographic Funeral in Bongo: Old Anai, 1849-1971 (1972), which chronicles the funeral ceremonies for a 122-year-old man in a Mali village (one of countless films Rouch has made about the rituals surrounding death), the appeal to the spectator seems less scientific than participatory, even celebratory. It’s been over a decade since I’ve seen this lyrical feature, but I remember it less as a “study” than as a mesmerizing experience, roughly akin to an extended performance by John Coltrane.

Such experiences are a little difficult to reconcile with the less personal narrative goals of an Indiana Jones adventure, which commonly turn the equivalents of Rouch’s heroes into spear carriers, camp followers, and cannon fodder to back up Harrison Ford’s romantic exploits. It’s certainly true that Rouch’s African adventures have their own traces of romanticism and idealism, and part of their interest is undeniably a related form of exoticism. But where Les maîtres fous, The Lion Hunters, and Jaguar decisively and definitively part company with Hollywood, and join hands with only a handful of other contemporary films–including, I should add, the remarkable To Sleep With Anger — is in their harking back to an earlier oral tradition of story telling, the tradition of the folk tale and the parable, which has much deeper roots than the TV commercial-derived telegraphic punchiness of recent Hollywood narrative. In more ways than one, it is a tradition that both precedes and escapes those official histories that organs like the Chicago Tribune are devoted to expounding and perpetuating. If we survive long enough as a culture, it may even wind up outlasting them.