This appeared in the November 18, 1988 Chicago Reader. I’d probably rank this film higher now. — J.R.

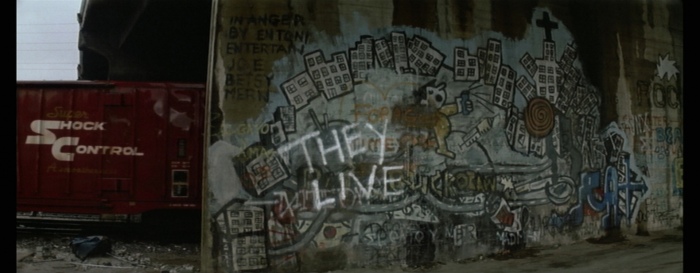

THEY LIVE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Carpenter

Written by “Frank Armitage” (John Carpenter)

With Roddy Piper, Keith David, Meg Foster, George “Buck” Flower, Peter Jason, and Raymond St. Jacques.

John Carpenter has managed to remain one of the few genuinely personal writer-directors left in genre moviemaking, having returned to relatively low-budget features with last year’s Prince of Darkness after the debacle of Big Trouble in Little China. From his clean ‘Scope compositions to his throbbing minimalist scores, he projects a simplicity of conception and a usually deft approach to story telling and straight-ahead action that are both refreshing and reassuring in an era of filmmaking when these modest virtues can no longer be taken for granted. As a disciple of Howard Hawks, he might even be said to preserve a scaled-down version of some of the familiar Hawks trademarks: cranky individualist heroes, flaky male/female relationships, camaraderie among professionals, confined spaces, and usually clear lines of demarcation between friends and foes.

All of these qualities are present to some degree in They Live, a paranoid science-fiction thriller about alien invaders loosely based on a short story by Ray Nelson. But a new element has been added to the Carpenter formula that upsets the usual balance of genre elements, for better and for worse, and places him in a separate universe from Hawks. A contemporary satiric thrust makes this movie, according to Lewis Beale in the Tribune a couple of weeks ago, “the most anti-Reagan film ever to come out of Hollywood.” Maybe it is and maybe it isn’t; but if it is, it seems to me that the Hollywood cinema as a whole has a lot to answer for.

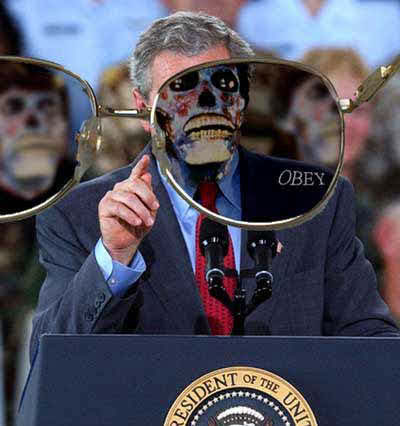

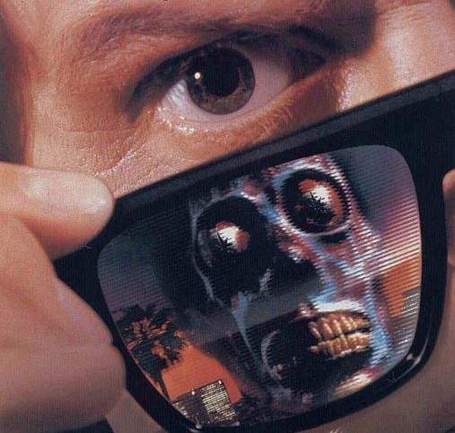

The central premise of They Live, which the nameless and homeless hero (Roddy Piper) and his itinerant black co-worker Frank (Keith David) gradually uncover, is that aliens from outer space have already taken over the world — or the United States (the two are regarded as interchangeable). These aliens cannot be seen without the help of special sunglasses. Once the hero and Frank put on these sunglasses (and later, undetectable contact lenses), they can see that large portions of the ordinary populace are in fact hideous monsters with silvery, bulging eyes, protruding teeth and gums, and dark splotches on their faces, and that ordinary posters, magazines, and consumer products are in fact projecting subliminal messages, such as “Obey,” “Conform,” “Marry and reproduce,” “No independent thought,” “Watch TV,” “Submit,” “Buy,” “Consume,” “No ideas,” “Surrender,” “Stay asleep,” and “Do not question authority.” Dollar bills say, “This is your God.”

It turns out that most of the population is either under hypnosis (from TV signals) or consciously collaborating “for business reasons” with the aliens in their mission as “developers.” They want to turn the earth into “their third world,” contaminating the atmosphere so it will be like “their atmosphere,” and treat all the hypnotized humans as cattle — a jaundiced view, in short, of the Reagan agenda. The only organized counterforce, whose mission is to alert the populace to what’s happening — “They Live, We Sleep” is one of their slogans — is a pathetically small minority working out of a small black church across from the shantytown where the hero and Frank stay. Later, after the police raid the premises and destroy the shantytown, the group meets at a warehouse, which is raided in turn. After attempting, without much success, to broadcast on TV information about what’s happening, they conclude that their only hope is to destroy the aliens’ TV transmitter.

Carpenter has been in the past a conservative director. But there’s no mistaking the film’s satiric intent, which he expounded upon in his interview with Beale. There Carpenter linked Reagan’s presidency to “fascism” and “the rise of the fundamentalist right and the kind of mind control they’re putting out.” Oddly, Carpenter underestimated his audience intellectually while overestimating them economically by concluding, “My prediction is a few folks will get [the allegory], but most will say: ‘What is he talking about? Is he talking about me?’ Then they’ll get in their BMWs, drive home, take off their expensive clothes and Rolex watches and slip into their Jacuzzis and say, ‘Nah, that’s not about me.'” For whatever it’s worth, both times that I saw They Live, the audience seemed to be fully clued in to what the film was about, and I sincerely doubt that any of them owned a Jacuzzi.

In fact, the movie is a confusing blend of anti-Reagan satire and genre conventions that make the film every bit as crass, amoral, and mulishly blinkered in its many rightwing assumptions as the attitudes it is ostensibly attacking. It all adds up to an ideological incoherence that is rather suggestive in relation to the recent presidential election. How, one may wonder, could a majority of voters have opted for a one-time wimp who, if one accepts the persuasive evidence of the recent Iran-contra documentary Coverup, is one of the world’s biggest drug dealers yet got elected on promises to deal harshly with drug dealers? How does one reconcile this campaign’s designation of “liberal” as a dirty word — by Democrats and Republicans alike — with the plethora of liberal promises and sentiments sprinkled into Bush’s speeches? If such contradictions can’t be reconciled, we can at least try to understand some of the processes (such as combining liberal sentiments with right-wing rhetoric) that make them possible; and They Live may offer a few clues about how we’ve arrived at such an impasse.

Ideologically speaking, Carpenter’s films generally project an innocence and naivete in relation to their conservative or reactionary underpinnings that are very much in keeping with the influence of Hawks (as well as Hitchcock). This naivete is quite contrary to the borrowings Carpenter’s films have made from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, an independent, non-Hollywood effort whose conscious satiric thrust is liberal or radical. As Robin Wood noted about Carpenter’s first two features in Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan, “The film-buff innocence that accounts for much of the charm of Dark Star can go on to combine (in Assault on Precinct 13) Rio Bravo and Night of the Living Dead without any apparent awareness of the ideological consequences of converting Hawks’ Fascists (or Romero’s ghouls, for that matter) into an army of revolutionaries.”

Carpenter’s macho heroes — played most often by Kurt Russell (and in They Live by ex-wrestler Roddy Piper) — are fond of snapping out acerbic John Wayne one-liners, and his villains are as faceless and as unambiguously malignant as those in Hawks’s Rio Bravo and Hitchcock’s The Birds. Romero’s ghouls, on the other hand, are both individuated and often associated with groups considered marginal: ghetto blacks, Hare Krishnas, bikers, nuns, etc. The aliens of They Live, significantly identified as “ghouls” in the credits, are essentially gooks to be wiped out by the hero and Frank, who charge with guns through their midst Rambo-style, mowing them down. Whether they might represent not merely Reaganites but Japanese and Iranian businesspeople taking over Los Angeles real estate is more debatable, but the least that can be said is that the xenophobia of most American war films is emulated rather than contested by Carpenter’s overall treatment.

The combination of a left-wing message with right-wing rhetoric isn’t, of course, the exclusive property of a Carpenter, and it must be admitted that he handles the fusion more convincingly and less equivocally than Dukakis did when he boarded a tank and donned a helmet during the campaign. It’s a tradition that stretches back to many of the populist stances of Huey Long and George Wallace; the assumption is that hyperbolic macho bluster is the only acceptable way to make any political point and be taken seriously. Movies, like candidates, look for one-liners to tie into ad campaigns, and the designated one-liner in They Live could probably work just as well for Bush/Quayle if they run for reelection in ’92. It’s delivered by the hero when he bursts into a bank with a gun and ammo belt: “I have come here to chew bubble gum and kick ass.” (Pause for dramatic effect.) “And I’m all out of bubble gum.”

Other one-liners figure when the hero wants to comment on the ugliness of female aliens (male aliens, of course, never occasion such epithets): “You know, you look like your head fell into a cheese dip in 1957.” Or discriminating between a female human and a female alien: “You, you’re OK. You, you’re fucking ugly, formaldehyde-face.” Or to a female alien primping before her reflection in a shop window: “That’s like pouring perfume on a pig.” The sexist glee of these giddy thigh-slappers, made “acceptable” only because they’re directed at aliens, is supposed to be mysteriously linked up with anti-Reagan satire, but the mixture won’t wash: it isn’t the moral ugliness of Reaganism that we’re being asked to laugh at.

Like political campaigns, movies generally traffic in myths rather than ideas, and the conspicuous absence of ideas in They Live (apart from the loose central premise) can be partially accounted for by its abject submission to mythology. Roland Barthes describes the mythologizing process clearly in his essay “Myth Today” when he notes that “myth is depoliticized speech,” and goes on to explain its function as follows:

“One must naturally understand political in its deeper meaning, as describing the whole of human relations in their real, social structure, in their power of making the world. . . . Myth does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact. . . . In passing from history to nature, myth acts economically: it abolishes the complexity of human acts, it gives them the simplicity of essences, it does away with all dialectics, without any going back beyond what is immediately visible, it organizes a world which is without contradictions because it is without depth, a world wide open and wallowing in the evident, it establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves.”

This is the world — the only world, alas — in which Carpenter’s antiyuppie and anti-Reagan satire has meaning. It helps to explain why, before Frank is willing to look through the special sunglasses and see what the hero sees, he has to engage in a fistfight of mythical dimensions with the hero. This nasty, pounding battle lasts over six minutes — a veritable showstopper that makes even the alien invasion appear secondary.

Although this protracted bashing session makes very little sense in terms of character motivation or plot, there are plenty of ways it can be explained or justified. There’s the Hawksian explanation: buddies have to slug it out before they can become friends (see, for example, Red River or Hatari). There’s even, as a friend points out, a Marxist explanation: workers are pitted against one another rather than against the ruling class that enslaves them both. (Frank’s subsequent wistful comment about the aliens supports this: “Maybe they’ve always been here — loving it when we hate each other, kill each other.”) There’s also the commercial explanation: former wrestler Roddy Piper gets to show his stuff. And finally there’s the satiric explanation: some people would rather get their heads bashed in than see what’s right in front of them.

On the crude level of this latter explanation, Carpenter’s satire makes a certain amount of sense. But there’s a moment in the movie’s delightful coda — after the aliens’ transmitter explodes and the hypnotic spell is broken, showing the aliens for what they are — that is sadly and ironically telling. One of the fleeting gags shows us Siskel and Ebert as aliens fulminating on TV about “filmmakers like George Romero and John Carpenter” who have “gone too far.” One gets the point, and it’s nice to see Carpenter identifying with Romero’s camp for a change. But unfortunately the parallel doesn’t pan out. Unlike Romero, he hasn’t gone far enough.