From the June 10, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

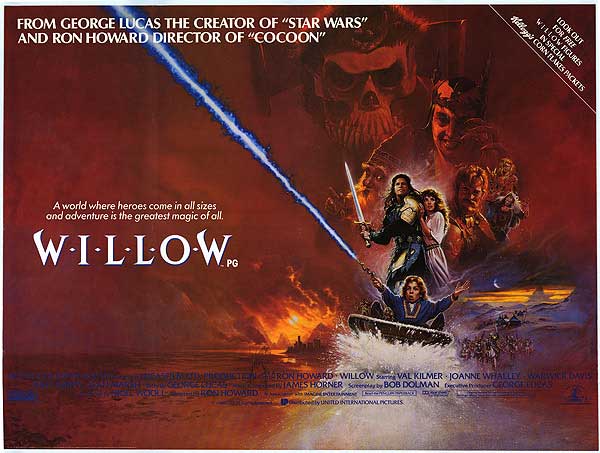

WILLOW

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Bob Dolman and George Lucas

With Val Kilmer, Joanne Whalley, Warwick Davis, Billy Barty, Gavan O’Herlihy, Jean Marsh, Pat Roach, and Patricia Hayes.

As one of those spoilsports who actively disliked Star Wars when it burst on the scene 11 years ago, enjoyed The Empire Strikes Back (1980) even less, and happily managed to miss both Return of the Jedi (1983) and Labyrinth (1986), I can’t say that I approached George Lucas’s latest ecumenical blockbuster with expectations of much pleasure. Nevertheless, now that his latest fantasy epic has confirmed my nonexpectations, I can’t help but wonder why Willow has been getting such a drubbing from the same reviewers who responded to the early Lucas mega-hits with such enthusiasm. Is it really all that different from its predecessors?

Lucas’s reputation seems to be passing through the same sort of vicissitudes as Ronald Reagan’s: a few years of euphoric tub thumping while the future was getting steadily sold away under our feet, followed by recriminations and icon bashing, which seem motivated less by second thoughts than by certain automatic principles built into an economy of planned obsolescence. It isn’t a change, moreover, brought about by any striking evolution in public response: Willow has been performing well, if not spectacularly, at the box office, and one can safely bet that our next president will be the candidate who applies the lessons of Reagan’s feel-good salesmanship most successfully.

The analogy between Reagan’s mythmaking and Lucas’s isn’t intended frivolously. Both depend on a Disneyland view of history and culture — a denial of the present and future combined with a cozy foreshortening and leveling of the past. And Lucas’s distance from Walt Disney and Cecil B. De Mille is roughly equivalent to Reagan’s from Teddy Roosevelt and Richard Nixon — the difference between facelessness and cranky individualism, between homogenized formula and obsession. The fact that Reagan could name his ballistic missile program after Lucas’s blockbuster, describe it as a gesture toward peace, and add, “The Force is with us,” is not entirely coincidental. Both Reagan and Lucas are media “visionaries” who have built their respective empires on the principle of painting by numbers — a soothing activity that relaxes the mind.

In Lucas’s case, at least, we know from Star Wars what the preordained mixture consists of: bits of Kurosawa, The Wizard of Oz, the Old Testament, Disney, Riefenstahl, the Brothers Grimm, Flash Gordon, a few sprigs of myth scholar Joseph Campbell, and whatever else Lucas may have on hand in his well-stocked suburban kitchen — in the case of Willow, Gulliver’s Travels, Tolkien, and the hideous Speaking of Animals shorts of the 50s — all fed into a blender. What comes out has the nerveless consistency of cold mush, or nursery wallpaper.

A female baby Moses destined to set her enslaved people, the Daikinis, free from the evil Queen Bavmorda (Jean Marsh) is discovered in the rushes by a peaceful community of dwarfs known as the Nelwyns. She gets taken in by a farmer and aspiring magician named Willow Ufgood (Warwick Davis). With the help of Daikini swordsman Madmartigan (Val Kilmer) and Daikini rebel Airk (Gavan O’Herlihy), Willow protects the baby while returning her to her homeland, defeating nasty Bavmorda and her head henchman, General Kael (Pat Roach), in the process.

Romantic interest is provided by Madmartigan and Sorsha (Joanne Whalley), Bavmorda’s daughter — a phallic villainess who specializes in castration threats until Madmartigan catches her with her armor off, when she becomes soft and pliable. Comic relief is largely supplied by scatological gags (e.g., the baby throws up on someone) and by the Brownies, miniature buffoons with French accents who also form the basis for some decidedly less than state-of-the-art special effects.

On the plus side are some lovely mountain landscapes — the movie was shot in England, Wales, and New Zealand — and some effective transformations near the end, when Raziel (Patricia Hayes), a fairy godmother type initially trapped in the body of a muskrat, briefly turns into an ostrich, turtle, and tiger before reassuming her human shape. But this is only to suggest that, like the Chartres cathedral (another potential ingredient in the Lucas blender), despite its monolithic construction, Willow occasionally displays a few personal, quirky details contributed by anonymous craftsmen.

Most of the formulaic conventions of Star Wars are still fully in force. While the movie was produced in association with something called Imagine Entertainment, imagination is conspicuous only by its absence. Yet given Lucas’s insistence on adhering to the “proven” and the already processed, how could it be otherwise?

Consider the use of foreign accents and ethnic groupings. Disney’s recourse to such stereotypes in the early 40s — from the nationalities of Pinocchio (including English and Italian villains and an American boy-hero and Blue Fairy) to the bebop crows in Dumbo — was admittedly more vulgar, but at least it had an ideological directness that honestly reflected the biases of both Disney and much of his audience. The same could be said of De Mille (Luc Moullet’s inspired gloss of the 1956 version of The Ten Commandments was: “Just a straight line, no dialectics: Ramses stands for Mao Tse-tung, and Moses for De Mille himself”). And at least Disney and De Mille gave us such abstract set pieces as the Dance of the Pink Elephants and the Parting of the Red Sea; Star Wars and Willow give us only live-action storyboards.

And how does Lucas handle ethnicity and nationality? In Star Wars he gave us both stingy Jewish merchants (the Munchkin-like Jawas) and an homage to Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda (in the final scene), and without owning up to the ideological implications of either, merely treating them as two more arbitrary ingredients for the MixMaster. In like fashion, it took Mel Brooks in Spaceballs to point out that Star Wars‘ heroine was a Jewish American Princess and a Valley Girl to boot; all Brooks did was add some healthy vulgarity and directness to Lucas’s more surreptitious styling (as well as to Lucas’s packaging and merchandising). Similarly in Willow, the issue of who is English, who is American, and who is French seems relatively unfelt and arbitrary, and the use of such varied nationalities becomes a substitute for imagination rather than a means of focusing it (as it arguably was in the better Disney and De Mille efforts).

Compare the designs of the Nelwyns’ musical instruments in Willow with the wilder inventions of Dr. Seuss in the dungeon sequence of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T., a neglected fantasy of the 50s — or put Willow‘s sub-Disney castle next to the one in Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy — and you start to get an idea of what distinguishes genuine fantasy from Lucas’s visual Muzak. The fact that Ron Howard, a director who usually has a gentle touch, was putatively put in charge here counts for less than the fact that Lucas, the executive producer, is directing Howard. Even the in-jokes lack bite: naming the head villain after Pauline Kael might sound like a sly dig, but Kael herself recently labeled it an “hommage à moi.” Thanks to the movie’s blandness, who can tell the difference?

The cardboard characters and predictable monsters in Willow seem to have strayed out of TV commercials, and considering the movie’s multiple spin-offs, this is where they’ll probably wind up anyway. In this respect, the movie is little more than an ad for its ancillary products — which become, in turn, ads for the movie, signifying a little of everything and a lot of nothing in the process. So if you have to take your kids to this, make sure to rent Spaceballs afterward, as an antidote.