From the Chicago Reader (May 27, 1988)….Seeing a more recent Konchalovsky picture, the powerful Holocaust drama Paradise, at Mar del Plata, I was reminded of what a terrific filmmaker he can be, which whetted my appetite to resee his powerful Runaway Train (a recent Twilight Time Blu-Ray that was waiting for me when I returned to Chicago). — J.R.

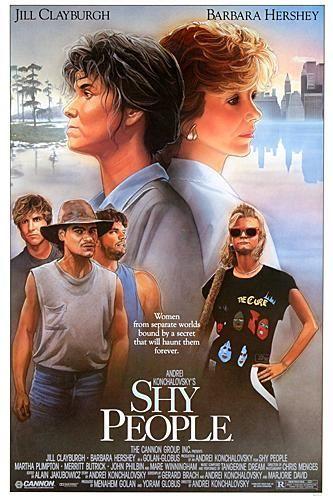

SHY PEOPLE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Andrei Konchalovsky

Written by Konchalovsky, Gerard Brach, and Marjorie David

With Jill Clayburgh, Barbara Hershey, Martha Plimpton, Merritt Butrick, John Philbin, and Mare Winningham.

I still have a lot of catching up to do with Andrei Konchalovsky. Out of his 11 or so features to date, the last 4 of which were made in the United States, I’ve seen prior to Shy People only 2. The Soviet Asya’s Happiness (1966), a film made with and about Russian peasants, was suppressed for many years because of its supposedly “gloomy” depiction of rural life but surfaced at the San Francisco Film Festival a couple of months ago. The other was Runaway Train (1985), costarring Jon Voight, Eric Roberts, and Rebecca DeMornay and adapted from a script by Akira Kurosawa. But a couple of things are already becoming clear from this limited if striking evidence. One is that he’s a very good (if not great) director regardless of where he’s working. The other is that he currently represents something singular and rather fascinating — a Soviet director who makes commercial American movies that somehow manage to be commercial, American, Soviet, and serious, all at the same time.

Reportedly because of his second marriage to a French translator in Moscow — Konchalovsky has the rare good fortune to be able to live and travel abroad without renouncing his Soviet citizenship, so he can’t be viewed as a melancholy exile like the late Andrei Tarkovsky. Nor can he be regarded as a director who invariably makes films about his homeland. Ironically, the qualities in Runaway Train and Shy People that seem to me most Russian their allegorical, mystical, poetic, pantheistic, and fairy-tale elements — are not especially evident in Asya’s Happiness, a more loosely constructed and neorealist sort of narrative filmed in black and white.

The transcontinental origins of Runaway Train and Shy People need to be considered as well. The former, derived from a script by a Japanese filmmaker, was written by Djordje Milicevic, Paul Zindel, and Edward Bunker. Shy People was conceived by Konchalovsky in Russia ten years ago, while he was making his epic Siberiade, and was subsequently written with Gerard Brach in Paris, with Liv Ullmann and Melina Mercouri as the projected stars and reportedly a remote Greek island as the projected setting.

That Shy People now stars Jill Clayburgh and Barbara Hershey and is set in the Louisiana swamps may seem like a wrenching change, but to all appearances the transposition has been a seamless one; the story seems fully integrated in its present location. A well-to-do, middle-aged divorcee named Diana Sullivan (Clayburgh), living in Manhattan, invites her rebellious teenage daughter Grace (Martha Plimpton) to join her on a trip to the bayous to hunt up some distant relatives. The specific reason for the trip is an article she is researching for Cosmopolitan, part of a series about family trees. (“Roots for honkies” is Grace’s indelicate way of describing the project.) Taken by motorboat to their remote destination — a hillbilly family of five lorded over by the mistrustful widow Ruth (Hershey) — they are dropped off for a two-day visit, and the remainder of the movie deals with the elaborate consequences of this rough encounter, including the profound changes that take place in both families.

Diana quickly discovers that Ruth’s life pivots around two “primitive” myths about her own immediate family: that her dead husband, Joe, is still alive, watching and hearing everything the family does, and that her oldest son Mike (Merritt Butrick), who currently runs a seedy strip joint in the nearby town, is dead (or, more precisely, never lived — Ruth has scratched out every photograph of him). Meanwhile, Diana confronts Grace with a fact that she’s discovered by spying on her daughter in New York — that Grace is currently having an affair with Andre, a 40-year-old former boyfriend of her own who does a lot of drugs.

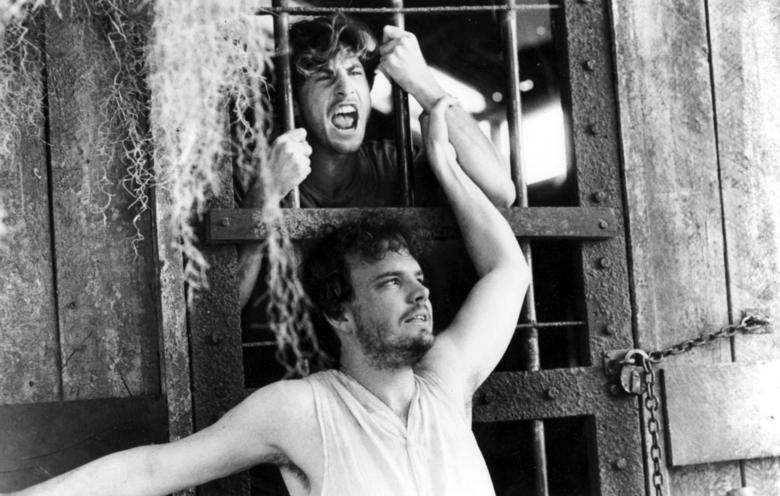

These discoveries turn out to be only the beginnings of the characters’ rude shocks. Before the visit is over, Grace has introduced some of Ruth’s sons to cocaine, had sex with one of them, and been nearly raped by another; Ruth has confronted her wayward son Mike, shot a man who injured another son, and bought her pregnant daughter-in-law (Mare Winningham) a battery-operated TV (itself a radical and “violent” act, in the movie’s terms, considering the family’s primitive and isolated existence); and Diana has encountered nothing less than the ghost of Joe — to begin a list that is by no means exhaustive.

The plot, as in Runaway Train, can be regarded as extremely schematic, as well as improbable — a veritable lifetime of dramatic events and revelations is compressed into a matter of hours — but not in a way that blunts the overall effectiveness of the material. The acting is uniformly good, and if Hershey’s efforts to achieve the impossible by making us believe in her as a genuine rustic are too plainly visible to succeed, her performance is still an honorable failure at the very least. Clayburgh, by contrast, is flawless (in an admittedly much easier part), and it is good to see her again after such a long absence from the screen — preceded, in the 70s, by what may have been overexposure. (Neither actress, however, approaches the uncommon brilliance of Voight in Runaway Train.)

One of the stronger aspects of the movie’s comparative anthropology is that it isn’t loaded moralistically, and isn’t contrived to score too many obvious points; our impressions of all the characters are gradually altered, but not simply or obviously, and it isn’t a competitive game in which there are winners or losers. The absence of a father in both branches of the family carries a great deal of weight, but no facile parallels are made; indeed, unless I missed something, the fact that Diana is a divorcee rather than a widow comes from the film’s press materials rather than any pointers in the dialogue.

The film opens in New York with an extraordinary aerial shot and extended camera movement that curves and doubles back on itself, moving from a bird’s-eye view of the streets to the balcony of Diana’s apartment. With its densely layered procession of sounds as well as sights — suggesting some of the ambience of Rear Window and the opening shot in The Conversation — this movement defines a complex and mysterious trajectory that becomes as dense and unpredictable as the later Heart of Darkness journey to Ruth’s house in the swamps. Although the film as a whole is framed by the relationship between Diana and Grace, and initially presents the country relatives from Diana and Grace’s “civilized” viewpoints, the story is never reduced to either a simple reversal of values and vantage points or a series of complacent parallels once we get to know the backwoods family better. In the final analysis, all of the characters are viewed objectively, critically, and sympathetically.

One doesn’t want to say too much more about a film that makes and provokes its own discoveries, but it is worth pointing out briefly that, like Runaway Train, Shy People creates some healthy confusion about the usual arbitrary distinctions Americans make between art and entertainment. As luck would have it, I saw both movies with “real” audiences rather than at private press screenings, and there was never a point during either when one felt the unnatural strain and hush that greets most “art movies.” The elements of allegory and poetry in Shy People, which make for a rather theatrical plot construction, lead to none of the self-consciousness that greets films by Ingmar Bergman; the audience was clearly with what Konchalovsky was doing from the beginning, proving in effect that what I’ve been describing as the “Russianness” of this movie, in no way interferes with its fidelity to the home truths found in a Louisiana swamp.