Françoise Romand’s Mix-up is surely one of the greatest films I’ve ever reviewed, and I can happily report that it’s become available in recent years on DVD (which isn’t to say that it isn’t still grossly neglected); you can even find it on Amazon in the U.S. This article appeared in the February 26, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader, and eventually it led to my becoming friends with Romand. — J.R.

MIX-UP

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Françoise Romand.

ANATOMY OF A RELATIONSHIP

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Luc Moullet and Antonietta Pizzorno

With Moullet and Christine Hébert.

GAP-TOOTHED WOMEN

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Les Blank.

While the issue of representation is at the cutting edge of most debates about film, it usually gets posed in relation to fiction features; documentaries, ranging from Shoah to the evening news, are commonly exempted. The unspoken assumption that nonfictional form is a discardable, see-through candy wrapper — a means of organizing and containing information, which can safely be ignored once we get to the goodies inside — not only keeps us ideologically innocent but limits the kinds of content we may find permissible in documentaries.

Many valuable documentaries, of course, exist chiefly to let certain voices be heard that might otherwise remain silent: Carole Langer’s Radium City, about a radioactive town in Illinois, is one such example, and Deborah Shaffer’s powerful account of the Sandinista struggle, Fire From the Mountain (which is playing this week at Facets), is another. Such films are important as documents rather than as texts, and we attend to them for the stories they tell, the people they show, and the subjects they explore, usually without inquiring into the kinds of rhetoric employed. Functionally they can be regarded as disposable journalism, which is certainly no disgrace: once a document takes us somewhere, it has effectively done its work, and ideally we can carry on from there without its help. (Arguably, if this kind of work gets overvalued and fetishized — as happened to some extent with The Sorrow and the Pity and Hearts and Minds — it might become a substitute for action rather than a vehicle for generating or implementing our activity.)

But another kind of documentary resists such pragmatic uses, and in fact aims to stage a crisis in its own forms of representation, which gives this kind of documentary a different functional value. Such works are likely to last longer because we can continue to learn from them, and what we learn has more to do with the process of signification itself, so there is no wrapper to be discarded. Indeed, we may find ourselves saving the wrapper even after all the paraphrasable “content” is absorbed.

The three films under review, all showing in the Film Center’s “Stranger Than Fiction” series this weekend, all have some relation to this second category, with varying degrees of success. Les Blank’s Gap-Toothed Women, a half-hour short, has in some ways the most unusual subject, but compromises it with a rather glib and mechanical form. A number of gap-toothed women from different walks of life are interviewed, and a wealth of material about being gap-toothed and female is imparted.

We get a little lecture about Chaucer’s Wife of Bath and the association of her gap-toothedness with lechery; we see a Garfield comic strip on the subject, hear a folk song about it, watch a woman stop people on the street to inquire if they’re gap-toothed, observe another giving an ersatz commercial for “tooth plugs” sold at a Santa Monica “tooth shop,” and hear still another talk militantly about “gap power.” Model/actress Lauren Hutton, cartoonist Dori Seda, truck driver Rene Morena, and Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor (addressing the Salvation Army) are among the many gap-toothed women featured, and it’s typical of the film’s jauntiness that there’s a cut from the latter to gap-toothed belly dancer Sharlyn Sawyer.

Part of what sets my own (gap) teeth on edge about the film is that many of the interviews end with a freeze-frame — the tackiest trope in contemporary cinema, commonly employed nowadays to end films that otherwise have no ending, and used elsewhere indiscriminately by filmmakers with a dead spot in their brains, a bit like writers (apart from Céline) who can only end their sentences with “. . .” This device is typical of the kind of California spaciness and folksiness that makes Les Blank the Richard Brautigan of film; and in a movie that’s so pleased with its own enlightenment and good intentions — as much about Bay-area life-styles as about anything else, teeth included — the trouble with such giddiness is that it makes the subject evaporate before it’s even had a chance to settle.

If Blank and his collaborators (cofilmmakers Maureen Gosling, Chris Simon, and Susan Kell) are ultimately done in by their arch uses of film rhetoric, Luc Moullet and Antonietta Pizzorno attempt to eliminate film rhetoric from their discourse entirely — which is of course impossible, although their calculated disdain for “technique” almost makes this idea begin to seem plausible. The most neglected of New Wave directors, Moullet differed from his fellow critics on Cahiers du Cinéma in the 60s in his rural and working-class origins, his leftist anarchism, and his distinctive taste for Hollywood B-films. (He was the first French critic to applaud Sam Fuller, Gerd Oswald, Douglas Sirk, and Edgar G. Ulmer, among others, long before most American critics knew who they were, and he wrote a book about Fritz Lang, which Brigitte Bardot can be seen reading in the bathtub in Godard’s Contempt.)

Contrary to most accounts, it was Moullet rather than Godard who first observed that morality was a matter of tracking shots — significantly, to the best of my knowledge, Moullet has never even been able to afford a real tracking shot. And it was he who countered no less a semiologist than Roland Barthes (at the Pesaro Film Festival in 1966) with the pointed observation that “language is theft” — a Marxist refutation of studio glitz and rhetoric that also underlines the contrived artlessness and personal/political directness of all Moullet’s own films to date. Celebrated by Eustache, Godard, Rivette, Straub, and Varda, he has made several shorts and at least half a dozen features, including a minor masterwork about borders and smuggling (Les contrebandiéres); a French Alpine western, with Jean-Pierre Léaud, called A Girl Is a Gun; and a documentary about teaching himself how to swim (My First Stroke).

None of Moullet’s films has received U.S. distribution, and this alone makes the appearance in Chicago of Anatomy of a Relationship (1975), his fourth feature — financed by a computer error, which is recounted in the film — an event of some importance. A reenactment of a crisis in his real-life relationship with Pizzorno, made a full decade before Henry Jaglom’s Always, and the same year that Paul and Daniéle Gégauff restaged the breakup of their marriage in Chabrol’s Une partie de plaisir, this film by Moullet and Pizzorno (whose solo films — reportedly experimental and abstract — I’ve been unable to see) differs markedly from the other two by suggesting the total inadequacy of fiction as a model for perceiving real life.

The film complicates matters by casting Christine Hébert (a sometime underground filmmaker in her own right) as Pizzorno, with Moullet playing himself, thereby juxtaposing pseudofiction with pseudofact in a way that undermines the rhetorical strategies of both, leaving only a sweet, tragicomic pathos as residue. The graphic exposition of their sexual problems, which pivot around Moullet’s failure to give Pizzorno clitoral orgasms, has a noble reticence and tenderness as well as an excruciatingly funny and painful clarity. In comparison with the usual guff about such matters that fills our screens and minds, nothing is allowed to intercede between the filmmakers and their subject. Shortly before the end, Pizzorno puts in an appearance herself, and the discussion that the film would like to stimulate is launched within the movie itself. Apart from clothing styles, this is a film that could have been made yesterday.

Francoise Romand’s 1985, 63-minute Mix-Up, as densely packed as a 500-page novel, has the French title Méli-mélo, which my dictionary defines as a “jumble (of facts, etc); hotchpotch; medley (of people, etc); clutter (of furniture)” — all of which describes the film’s startlingly original method as well as its fascinating, evocative subject.

In November 1936, at a nursing home in Nottingham, England, two middle-class women, Margaret Wheeler and Blanche Rylatt, gave birth to two daughters. Through a mix-up in the files, each woman was presented with the wrong baby afterward — a fact confirmed only in 1957 after strenuous efforts by Margaret, who had suspected something was amiss from the beginning and retained a rudimentary contact with the Rylatts as a consequence. At this point, each 20-year-old daughter — Peggy, who had grown up with the Rylatts, and Valerie, who had grown up with the Wheelers — discovered that she had a different set of parents.

Romand’s major coup is to have enlisted the entire Wheeler and Rylatt families in her project — not merely to recount the story with all its complex ramifications, but to reenact it at crucial stages, using the original participants playing themselves at various ages, and reflecting in the present about what the whole experience meant and did to them. (Exceptions to this rule include Blanche’s husband Fred, who died in 1975; Peggy and Valerie as infants and toddlers; and, in a few abstract episodes set around parallel and diverging railroad tracks, the girls as preadolescents.) To make this enterprise even stranger, Romand stages and orders these scenes in a highly stylized manner, visually, aurally, and conceptually, in the families’ homes and surrounding locations.

As a consequence of these strategies, one watches much of Mix-Up in a kind of stupefied awe and amazement. One first tries to figure out how Romand managed to convince both of these proper English families to cooperate in such a bizarre avant-garde concoction. One then is further awed and amazed to gradually realize that Romand’s radical subversion of documentary conventions is strictly functional in exploring the implications and nuances of her subject. Indeed, the mix-up of the title refers not only to the switched babies but, in Romand’s dazzling presentation, to the confusions between fact and imagination, English and French sensibilities (the film was made bilingually for French TV), emotion and analysis, past and present, and tragedy and comedy.

The opening of the film is characteristic. A man (later discovered to be Charles Wheeler, Margaret’s quizzical husband) walks through a couple of doors with windowpanes toward the camera, discovers the unseen filmmaker, and declares, “Ah, c’est vous!” (“Ah, it’s you!”) — an acknowledgment of both the filmmaker and the fact that she’s French. The film makes elaborate use of windows, mirrors, doors, family portraits, snapshots, and home movies throughout, but just about the only other French that we hear in the film occurs much later, in a matching shot, when Charles passes a painted portrait of himself and declares, “Ah, c’est moi!” (“Ah, it’s me!”) A sequence occurring somewhere between these two shots poses Charles apparently next to this portrait, but we gradually see from his movements that it is actually a mirror reflecting the picture from the opposite wall. In another film, such conceits might seem forced and arch; here they go straight to the heart of the film — the question of identity and identification (of one’s self and others) — and guide us into the intricacies of the subject.

The film’s next two sequences, another matching pair, introduce us to Margaret and Blanche, the two mothers, both speaking to the camera. As the film develops, we begin to observe the salient differences between these women. Margaret, the better educated of the two, made her 20-year campaign to clear up the mix-up a kind of intellectual odyssey — she corresponded with George Bernard Shaw between 1944 and 1950 about the problem, contacted various scientists, and wrote to her husband when he was stationed in India in the early 40s for a blood sample. (Charles tells us about the latter while fixing Margaret a pot of tea; blood samples in test tubes are in front of him on the kitchen counter while he speaks, and we briefly hear sounds of an offscreen plane and bomb to establish the wartime context–a good example of how Romand can mix several modes of representation at once.)

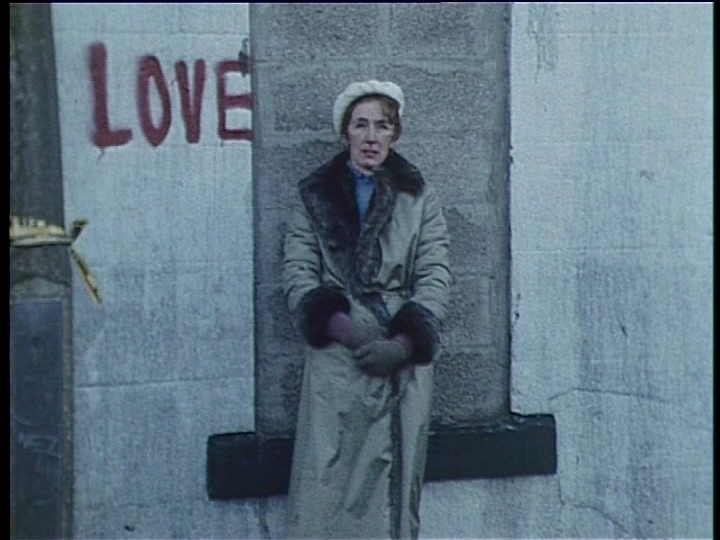

Blanche is both sillier and warmer than Margaret, and the film leaves us with no doubt that she was the better mother: while Peggy had a happy childhood, Valerie grew up feeling rejected. Margaret is filmed with her large boxes of correspondence about the mix-up, discoursing very rationally on the subject; Blanche appears in her “bowling” hat with her own neat scrapbooks, which are devoted both to the mix-up and to the images of pigs that she collects. (She was born, she cheerfully explains, in the Year of the Pig and believes that pigs will bring her luck.) [2018 correction: This is Margaret’s sister, not Blanche.]

We get to see a lot of Valerie and Peggy as well, and one of the most striking sequences frames each of them in turn on the street against a wall covered with graffiti. Valerie walks past the words “Val” in blue and “Peg” in red, and then stops to explain that Margaret/Peggy was her own middle name, and that in her teens she briefly adopted Peggy as her first name. (Elsewhere, she recounts how she adopted a hyphenated last name — before her marriage — to accommodate her fractured identity, after discovering that Blanche was her real mother.) We cut to Peggy in the same spot, who expresses her satisfaction with her name, and then moves with the camera to the right, past the word “regrets” in blue with a red question mark, before stopping and explaining that her only regret was that she didn’t grow up in a larger family. We then cut to Valerie in the same spot explaining her regrets, then walking past the word “love” in red and explaining that parental love was the main thing lacking in her childhood. (We later are told that while Blanche felt that she gained a daughter after 1957, Margaret felt that she lost one.)

While my description of this section may make it seem didactic, the sequence registers as exploratory, and receives its full impact from the context the film gives it — such as the fact that the fictional, preadolescent Peggy and Valerie, whom we periodically glimpse together in different configurations relative to parallel and diverging railroad tracks, are dressed in contrasting red and blue outfits. Similarly, Nicolas Frize’s effective, intermittent score creates rhyming and contrasting musical patterns that help to structure the sequences while complicating our responses to them–working against the documentary aspects and either romanticizing or objectifying the fictional elements.

Martin Wheeler (Margaret’s youngest son, now an adult) recalls a statement he overheard while crouching under a table at age 13 that first indicated to him that Valerie wasn’t his sister. As he speaks, the film cuts first to a 13-year-old boy crouching under a table, then to Martin himself crouching in the same spot as he continues to relate the anecdote. The strangeness of such moments shouldn’t blind us to the fact that Romand’s procedure, in effect, is to stage a form of group psychoanalysis with all the family members involved, a process of educating the participants as well as the spectators by guiding us all through the various aspects of the story.

Bringing about a crisis in representation here is not simply a matter of enlivening material that is already full of interest. (Sadly, and significantly, Romand adopts in her subsequent documentary, Call Me Madame — an in-depth portrait of a French transsexual author that showed at the last Chicago Film Festival — a fixed and conventional representational mode, and despite its interesting subject, this film pales in comparison with Mix-Up.) One reason we come to know as much as we do about the film’s varied cast of characters — a fascinating collection of individuals that extends well beyond the few examples cited here — is that Romand’s bold method stages a crisis not only in them but in us. As in all of the best innovative work, the radical formal departures are necessary tools in bringing a new and radical content to light.